I’m putting the finishing touches on a history of Plymouth Colony and have been thinking through a cluster of issues regarding names.

In a draft of my manuscript, I referred to the seventeenth-century Pokanoket sachems as Massasoit, Wamsutta (son of Massasoit), and Philip (son of Massasoit). These individuals lived at Sowams and then Mount Hope (present-day Warren and Bristol, Rhode Island, respectively), and they exercised regional leadership over many Wampanoag communities in what is now southeastern Massachusetts.

The first of these sachems is the leader with whom the Pilgrims formed an alliance in March 1621. English accounts referred to him as “Massasoit,” a Native word roughly meaning great leader or great sachem. The man’s name was Ousamequin. Somewhat later seventeenth-century English documents, including deeds, use this name. Nevertheless, most historians — including Nathaniel Philbrick in his best-selling Mayflower — have called him Massasoit. I did so as well, because I thought readers would be more familiar with that name. Even if they mispronounce Massasoit, it still looks more familiar than Ousamequin.

After Massasoit Ousamequin’s death, his son Wamsutta succeeded him as sachem. At this time, Wamsutta and his brother Metacom requested the Plymouth General Court to bestow on them the names Alexander and Philip, respectively. The court granted the request, but its own records continue to refer to him as Wamsutta, as do many deeds. I saw no reason to depart from those records, so I used Wamsutta in my manuscript.

By contrast, countless English records in the 1660s and 1670s refer to Wamsutta’s brother as Philip, the Pokanoket sachem during what became known as King Philip’s War. Beyond reasons of familiarity, it made sense to me to call this sachem Philip. A host of deeds and other documents from the time period refer to him as Philip. Moreover, while some English settlers and no doubt many Native people referred to the war by other names, I call it King Philip’s War. So Philip seemed the best choice.

I had twisted myself in knots, calling one sachem by his title, the next by his Native name, and the third by his English name. An entirely incoherent approach.

Two interactions have caused me to do some rethinking. First, Paula Peters — a Wampanoag scholar — read my manuscript and asked if I could call her ancestors by their actual names. Why call Ousamequin by his title? I call refer to William Bradford as “Bradford” or sometimes “the governor,” not as “governor.”

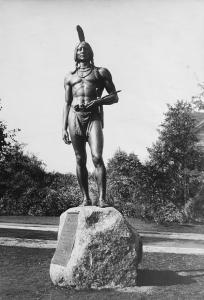

It was also helpful to read Lisa Blee and Jean O’Brien’s Monumental Mobility: The Memory Work of Massasoit. These scholars narrate the fascinating story of Cyrus Dallin’s Massasoit sculpture. [My career has stalked Dallin, in a way. The Utah-born and Massachusetts-based sculptor also created the Brigham Young monument on Temple Square and the Angel Moroni atop the Salt Lake City Temple]. Blee and O’Brien carefully distinguish among 8sâmeeqan (Ousamequin, they use the transliteration preferred by the Wôpanâak Language Restoration Project), “the Massasoit” (when referring to his role as paramount sachem), and the Massasoit monument.

It was also helpful to read Lisa Blee and Jean O’Brien’s Monumental Mobility: The Memory Work of Massasoit. These scholars narrate the fascinating story of Cyrus Dallin’s Massasoit sculpture. [My career has stalked Dallin, in a way. The Utah-born and Massachusetts-based sculptor also created the Brigham Young monument on Temple Square and the Angel Moroni atop the Salt Lake City Temple]. Blee and O’Brien carefully distinguish among 8sâmeeqan (Ousamequin, they use the transliteration preferred by the Wôpanâak Language Restoration Project), “the Massasoit” (when referring to his role as paramount sachem), and the Massasoit monument.

In 1913, the Improved Order of the Red Men, a “fraternal order limited to ‘physically, mentally, and morally sound’ white men,” resolved to install a monument to the Massasoit to be dedicated during the tercentenary of the Pilgrims’ arrival at Plymouth. I knew nothing about the IORM before reading Monumental Mobility. It was a large organization, with half a million members at its peak in the 1920s. The Pilgrim Society donated a tract of land on Cole’s Hill, and the IORM commissioned Dallin to make the statue.

What should the Massasoit look like? Dallin had already sculpted many powerful, muscular Indians, including his Scout and his Appeal to the Great Spirit. For Massasoit, he used a model, but not anyone from the Mashpee or other Wampanoag communities in Massachusetts. Instead, he borrowed John Singer Sargent’s African American model, Thomas McKeller. He gave Massasoit a feather (Ousamequin means “yellow feather”) and a peace pipe decorated with bears, corresponding with a pipe found in a burial ground.

Dallin completed his plaster model, and the bronze monument that is still on Cole’s Hill was cast in time for the tercentenary. Massasoit was unveiled on Memorial Day in 1921, in a crowd that included Dallin, a descendant of Ousamequin (Wootonekanuske, or Charlotte Mitchell), and a sea of white people dressed as Indians. On this occasion and at a dedication the next year, white speakers extolled Ousamequin as a symbol of friendship and peace. They envisioned him welcoming the Pilgrims who had (probably not really) stepped on Plymouth Rock, on the shore below Cole’s Hill. A tablet attached to the statue’s pedestal memorializes the “great sachem of the Wampanoags, protector and preserver of the Pilgrims.”

As it turned out, it proved impossible to fix memories of the Massasoit. First of all, he traveled. Dallin reluctantly donated his plaster model to the State of Utah, which displayed it in the state capitol and caused many visitors to wonder who it was and why it was thousands of miles from Massachusetts. The plaster model was replaced by a bronze cast at the Utah State Capitol in 1957.

Somehow or other Brigham Young University acquired the plaster cast soon afterwards. Then, Blee and O’Brien narrate, BYU’s art acquisition director — Wesley Burnside — used the model as part of a “tax shelter program in which artworks were overvalued so that buyers who intended to donate the object to a charitable organization could claim substantial tax deductions.” Although it was by no means clear that BYU held the title to the model, BYU officials authorized a series of casts. These ended up on the campus of BYU, at shopping plazas in Missouri and Illinois, and at the Museum of Native American Culture at Gonzaga University. At BYU, the “naked Indian statue” became a meeting place and the subject of many jokes about its brazen violation of the school’s honor code.

Meanwhile, back in Plymouth, Wampanoags, other Native Americans, and allies contested the meaning that the IORM and the Pilgrim Society had placed upon Massasoit. In 1970, the United American Indians of New England began gathering every November (on Thanksgiving morning) to mark a National Day of Mourning. They sometimes engaged in acts of protest, such as a 1995 burial of Plymouth Rock. In 1998, the Town of Plymouth installed a second marker near Massasoit, which reads: “Many Native Americans do not celebrate the arrival of the Pilgrims and other European settlers. To them, Thanksgiving Day is a reminder of the genocide of millions of their people, the theft of their lands, and the relentless assault on their culture.” As Blee and O’Brien conclude, statues “may be formed of stone and metal and appear set in place, but monuments are not fixed.” While some monuments are simply ignored and forgotten, others become contested sites.

Back to names. What to call the Pokanoket sachems? Should I stick with Massasoit, or instead use Ousamequin or 8sâmeeqan? I’m disinclined to use 8sâmeeqan, because I think it’s simply too jarring for non-specialist readers. It is not clear when the sachem adopted the name Ousamequin. He may have done so a decade or so after the arrival of the Pilgrims. The earliest English sources, mostly by Edward Winslow, refer to him as Massasoit. Even if he adopted the name later, however, I’m now leaning toward using Ousamequin, which appears in many records from the 1640s onwards.

What about Wamsutta (Alexander) and Metacom (Philip)? I’m inclined to stick with Wamsutta and Philip. Lisa Brooks uses Philip in her Bancroft-winning Our Beloved Kin. I quote from English sources that refer to Philip, and I refer to the mid-1670s war as King Philip’s War. To use Metacom or Metacom alongside those sources and references may confuse readers. And the sachem does seem to have embraced the name Philip, at least in his dealings with the English. In any event, I am confident that Philip alias Metacom cared far more about English encroachment on his land and authority than about what the English called him. Still, names matter. Thinking through names forces us to consider how we remember and write about individuals.