I’m very pleased to welcome Mark Elliott to the Anxious Bench. Elliott has taught modern European and Russian history at Asbury College, Wheaton College, and Samford University. He was the founding editor of the East-West Church and Ministry Report (1993-2017). He was also my Russian history professor at Wheaton College and has been my friend and mentor in Kentucky as I’ve begun my teaching career.

I’m very pleased to welcome Mark Elliott to the Anxious Bench. Elliott has taught modern European and Russian history at Asbury College, Wheaton College, and Samford University. He was the founding editor of the East-West Church and Ministry Report (1993-2017). He was also my Russian history professor at Wheaton College and has been my friend and mentor in Kentucky as I’ve begun my teaching career.

–David R. Swartz

***

In the early 1960s, when I was growing up in a suburb of Atlanta, Georgia, racial conflict was a fact of life in my church. In those years, Black families were moving in to neighborhoods closer and closer to my church, Pattillo Memorial Methodist. This precipitated “White flight” to Stone Mountain and other distant suburbs east of Atlanta. In moving east, Whites came closer to the massive carving on Stone Mountain honoring Confederate heroes Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and Thomas J. (Stonewall) Jackson, the largest relief sculpture in the world. Stone Mountain, cited in Martin Luther King, Jr’s “I Have a Dream” speech, was a favorite site for Ku Klux Klan rallies, one of which, out of curiosity, my teenage friends and I attempted to observe, only to be prevented by a police roadblock. Looking back, I am grateful I was prevented from attending.

Black families often had more children than the White families they replaced near my church, which put pressure on local schools. The city of Decatur approached Pattillo Memorial Methodist with a request to rent the Sunday school building for temporary classroom space. With so many church families moving away, our congregation certainly could have used the rental income. I clearly recall my father coming home one evening from a church board meeting very upset. He had urged the rental of the Sunday school building but was outvoted by congregants who could not abide the thought of Black children walking the halls of our church.

Around the same time, I remember attending a general congregational meeting in which a prominent church member stood to his feet and vowed never to let a Black family cross the threshold of our church. No wonder Martin Luther King, Jr., declared 11:00 a.m. Sunday morning the most segregated hour in America.[i] What a contrast to the warm welcome my wife and I received a decade later worshipping one Sunday at Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church, where Martin Luther King, Sr., and Jr. had co-pastored. Integration never came to our church because Pattillo Memorial Methodist merged with Avondale Methodist farther east, and the Pattillo property was sold to a Black congregation, Thankful Baptist, which worships there to this day.

Still, I can say all was not complete, unrelieved prejudice in our church. My youth pastor, Rev. Warren Harbert, and his wife, Jo, labored against the prevailing racism in our congregation. Just as many church families were departing the Oakhurst neighborhood of Decatur, Warren and Jo moved in. I recall visiting them in their new home, with Black neighbors all around, marveling at this concrete statement of opposition to the racial divide that was commonplace in early 1960s Atlanta.

In summer 1963, I remember a church youth choir tour to Savannah, Georgia, and a night ride downtown with teenagers from the church hosting us. As Blacks crossed the street in front of us, these Savannah teens called out “one,” “two,” and “three.” I finally figured out they were joking about “points” they would score for hitting this or that African-American. I think back on that Savannah joy ride with shame because, while I found my fellow teens’ “point system” awful and ugly, I said not a word of objection. No one earned “points” that night for running over Blacks. But this flippant devaluation of human life on racial grounds, so common across the South, did translate, only months later in October, into the racially motivated bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, killing four young Black girls attending Sunday school.

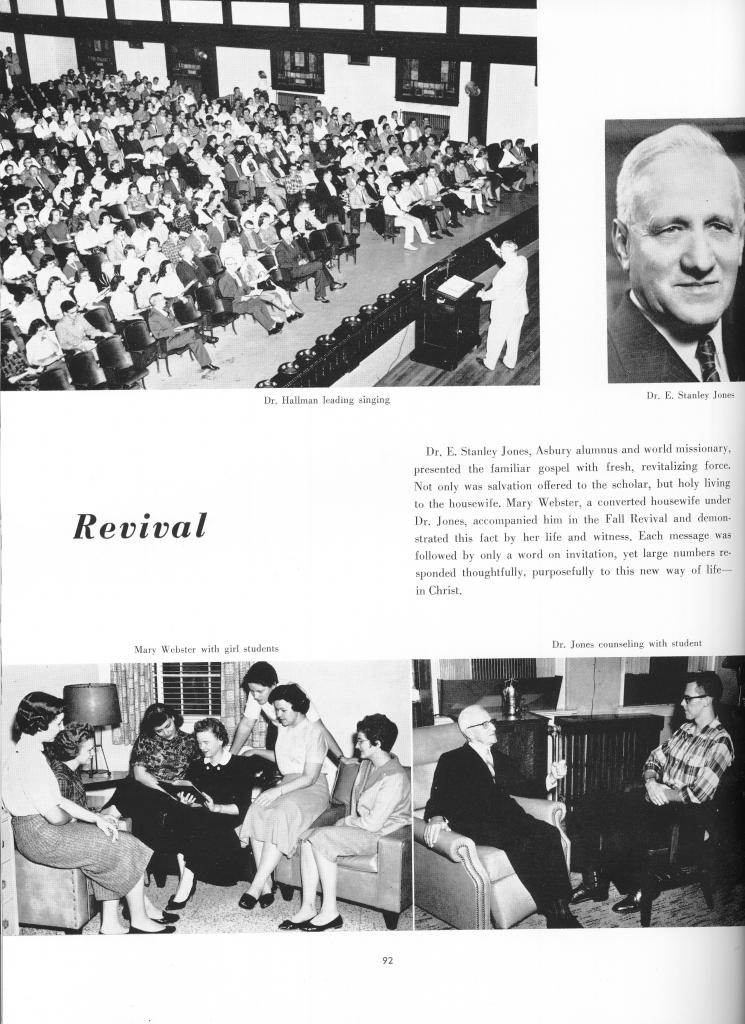

In 1965 I made my way to Kentucky to attend Asbury College, a small Christian liberal arts institution near Lexington, where my mother, my aunt, and my sister had graduated. Asbury, with the college president from Georgia and the chair of the board of trustees from Texas, was far too slow to integrate. One of its prods in the right direction was board member E. Stanley Jones, a widely respected and frequently published Methodist missionary to India. He knew firsthand how damaging America’s discrimination and violence against Blacks was to the cause of missions and to the image of America abroad, not to mention their contradiction of Christ’s teachings. Before my arrival on campus, back in October 1958, in an Asbury chapel message, Jones had decried the college’s refusal to admit Blacks, and in protest resigned from the board of trustees. A decade earlier, in 1948, this same E. Stanley Jones had published a biography of his friend Mahatma Gandhi, whom Martin Luther King, Jr., credited as contributing to his adoption of non-violent civil disobedience.[ii]

I will never forget April 4, 1968, a decade after Jones’s prophetic chapel sermon, when news of King’s assassination first hit Asbury’s campus. I remember exactly where I was standing–in front of Johnson Main Dormitory, named after the school’s retired Deep South president. A student from my very hometown, Decatur, Georgia, came up to me and said, “King deserved what he got.” I was shocked no end by this callous justification of murder. But to my everlasting shame, I did not take my fellow Georgian to task. What was wrong with me that I did not object to this blatant hatred for the leader of America’s Civil Rights Movement?

Do my personal encounters with issues of race and prejudice growing up in America’s segregated South have any bearing on Russia today? Unfortunately, I would argue they do, because racial discrimination is very nearly a universal human failing. Let me illustrate from personal experience.

In 1986, after twelve years on the faculty of Asbury College, I accepted a position at Wheaton College in suburban Chicago. Our four children, adopted from Vietnam and Colombia, had never experienced racial prejudice in small-town Kentucky, but, ironically, that was not to be the case in the North. Our oldest son, Fernando, was repeatedly the victim of racial profiling by police on the streets of Wheaton, Illinois. Fernando was never arrested, but police frequently pulled him over for a license check, while I was never pulled over while driving the same car.

I am sorry to say that two of my children experienced similar racial profiling in Moscow. In 1990 I led a Wheaton College student exchange with Moscow State University. On one occasion, as our group made our way into the Kosmos Hotel, my daughter, adopted from Vietnam, and an African-American Wheaton student, were the only ones blocked from entering. This “misunderstanding” was quickly righted, as I proved to the doorman that these young people indeed belonged with our exchange group, but it could not help leaving a bad taste in our mouths. Then in 1997 I was in Russia with my son, Pablo. In my dozens of times in Moscow since 1974, militia have never stopped me in the city’s famed subway—except that summer of 1997 when I was with Pablo. We even, on one occasion, were momentarily escorted into the interior of militia Metro holding cells, though fortunately not behind bars. Pablo’s Hispanic features were presumably mistaken for someone from the Caucasus or Central Asia. It is common knowledge how frequent document checks are for non-Slavs in Moscow, but only those corralled by the militia on a regular basis can know how demeaning it is. The question has to be asked: Does the singling out of individuals with particular “suspect” physical features improve safety? Or does such racial discrimination simply further alienate ethnic minorities and lead some to radicalization?[iii]

Czech dissident playwright Vaclav Havel made the remarkable journey from a Prague prison cell to a presidential palace in 16 months. Once in office he advised his fellow citizens that the truest test of Czechoslovakia’s devotion to democracy and human rights would be how they treated the minorities in their midst whom they liked the least. By this standard White America failed the test for centuries, including the century after the Civil War that ended slavery. Czechs and Slovaks—and many other European populations in the post-World War II era—have failed the test in their mistreatment of much-abused Roma. And for the foreseeable future, the test for Europe as a whole will be its Muslim immigrants. For Russia, the test comes in its treatment of its African and Asian exchange students and its Central Asian, Caucasus, Vietnamese, and North Korean immigrants and contract laborers.

From the perspective of Christian theology, the impetus for treating everyone with respect derives from the belief that every human being is created in the image of God. In addition, unpopular minorities—and by extension, unpopular religious minorities—deserve equal protection before the law on the basis of both Christian and Enlightenment principles. Unfortunately, these two foundations for equal justice for all run counter to the base tribalism and racially fueled nationalism that increasingly raise their ugly heads on both sides of the Atlantic, and indeed, worldwide.

___________________________________________

This essay is excerpted from a piece entitled “Growing Up in America’s Segregated South: Reminiscences and Regrets,” which has just been published online in the April 2019 issue of The Asbury Journal.

[i] “Segregated Churches Rapped,” Greensboro (NC) Daily News, 21 January 1964, A4.

[ii] E. Stanley Jones, Mahatma Gandhi: An Interpretation (Lucknow, India: Hodder and Stoughton, 1948); David Swartz, From the Ends of the Earth: Evangelical Internationalism in the American Century, forthcoming; Tom Albin, “A Man for Our Time: E. Stanley Jones,” Good News, January 6, 2016; Leonard Sweet, “Forward” to reprint of E. Stanley Jones, Abundant Living (Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 2014). On October 26, 1960, from Reidsville State Prison in South Georgia, Martin Luther King, Jr., wrote his wife, Coretta, asking for books from their home, including the Gandhi biography by Jones. Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters; America in the King Years, 1954-63 (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988), 363; Clayborn Carson, The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Vol. 5, Threshold of a New Decade, January 1959-December 1960 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1960), 531-32.

[iii] Matthew Kupfer and Bradley Jardine, “Cop Stop,” Moscow Times, April 13, 2017, 3.