Last year, I wrote several post about the relationship between Judaism and Hellenism, the issue that sparked the Maccabean revolt. The anti-Hellenist rebels won the war, and secured national independence. But that certainly did not mean the end of Greek influence on Jews, and indeed on the emerging Christian movement. In the light of some very recent archaeological finds, we now see just how thoroughly Jews continued to absorb Greek imagery and iconography throughout what we would call the early Christian centuries. That fact seriously affects how we understand the parallel trends among Christians in those very same years.

This image is available under a Creative Commons License

This image is available under a Creative Commons License

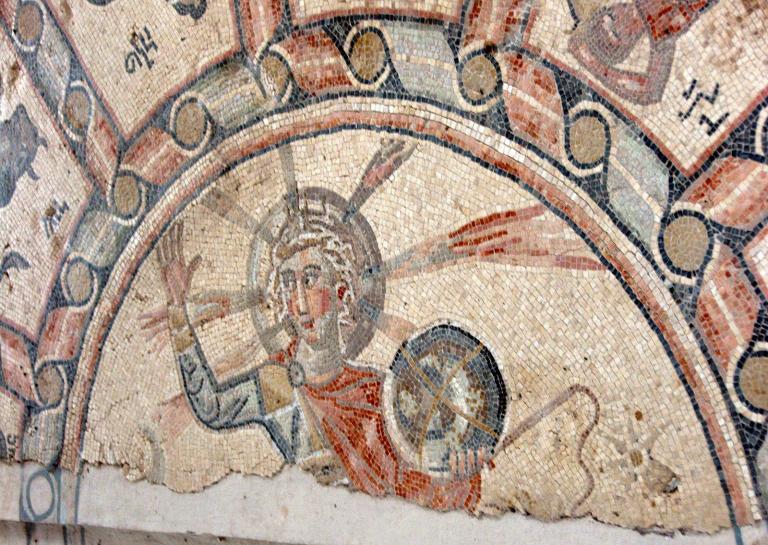

By way of introduction, this image depicts a detail of a mosaic floor in what once a magnificent synagogue at Hamat, Tiberias, on the Sea of Galilee, and it is a famous Israeli archaeological treasure. In the fourth century, this would have been the seat of the Sanhedrin, and as such the building called for lavish display. The mosaic in question depicts the Greek sun-god, Helios, holding the celestial sphere. He is at the center of a larger image of the whole zodiac.

Now, an obvious comment here is that Jewish tradition strictly forbade visual depictions of the deity, and in later eras, that suspicion extended to human figures in general, certainly in a sacred context. But the more early synagogues we find – from, say, between the third and the sixth century – the more evidence we see of the popular use of human figures, on a huge scale.

This is a vast topic that I will not get into here, but there are some really famous sites. You should follow the links cited here for some stunning works of art. One of the finest and earliest, from the 240s, stands at Dura-Europos in Syria, and it includes extensive murals showing Biblical scenes. All the characters are shown in the finest Hellenistic mode. Early in the fifth century, some wonderful mosaics were crated at the synagogue of Sepphoris/Tzippori, which is within walking distance of Nazareth. Again, Helios is in his sun chariot, but Biblical scenes also feature prominently.

Just over the past decade, a synagogue site at Huqoq (near Tiberias) has produced jaw-dropping art-works, again from the fifth century. I quote Amanda Borschel-Dan:

The scenes vary from well-known religious stories such as Jonah and the Whale, Noah’s Ark, and Pharaoh’s soldiers being swept away by the Red Sea and swallowed up by dozens of fish, to the pagan zodiac at the floor’s center, as well as a portrayal of what may be the first purely historical non-biblical scene in a synagogue — complete with armored elephants.

We now have a vast range of writing on these works, scholarly and popular. Some authors particularly address the question of “What is the sun god doing on the floor of ancient synagogues? Doesn’t that violate the second commandment?” As Mike Rogoff notes,

Jews recognized . . . that the universe is entirely in the hands of the Creator; but since any representation of Him was the most severe prohibition of all, they adopted and adapted a long-popular Mediterranean design to convey the idea. There was no veneration of the pagan deities or celestial bodies—after all, the congregation routinely tramped over them—and thus no violation of the second part of the Second Commandment [which states of images:] “…thou shalt not bow down unto them, nor serve them.

It’s useful to bear these parallels and precedents in mind when looking at Christian culture in the same era. One of the most famous early depictions of Jesus, from the Vatican Necropolis, seems to depict him as Helios. A great deal of ink has been spilled through the centuries noting how Christians came increasingly to depict their sacred characters in Greco-Roman guise, drawing heavily on the iconography of pagan gods and heroes. But as we see from those Jewish examples, that did not necessarily represent any kind of concession to syncretism. Rather, Jews and Christians alike were just using what they regarded as the finest aesthetic standards of the time, and using craftsmen who were used to creating figures of Heracles or Apollo.

At the end of the fourth century, St. John Chrysostom notoriously denounced Antioch Christians who freely ran off to synagogues, especially for the solemnity of the great holydays. When we read such accounts, it helps to recall that the physical appearance of the particular places of worship was not as radically different as we might suppose.

Incidentally, early Muslims were just as easy-going about using human representations, even if not in places of worship. Just look at the eighth century royal site of Qusayr’ Amra in Jordan, with its extensive human depictions, and again, with the zodiac and the constellations heavily prominent. And of course, Islamic traditions are even more strongly opposed to human imagery than were the Jewish precedents.

This whole story actually gets to a larger issue about how we understand early Christianity, at least in popular reconstructions, as opposed to serious scholarship. When we think of New Testament or early Christian times, we often imagine Judaism as we know it from medieval or modern manifestations, rather than the complex and multi-faceted phenomenon that actually existed at the time. Hence a great many sermons through the centuries that try to contrast Jesus’s liberal attitudes with the supposed rigidity of “the Jews” at the time – do excuse the rampant stereotypes here. Hence also the attempt to speak of different gospels as more or less “Jewish” or “Gentile,” when the supposed Gentile content had already been absorbed into Judaism long before Jesus’s time. Just witness generations of writing about the Gospel of John and its Logos theology.

The same golds true in the early Christian centuries. A common impression suggests that Christianity began in a Jewish matrix, and then became progressively more Gentile and Hellenized as it developed as an independent movement, breaking from that Jewish stem. One sign of that supposed rupture is the increased willingness of Christians to adopt visual imagery, and even to borrow from pagan iconography, and that process became ever more marked once Christianity became the state religion in the fourth century. But as I have suggested here, that idea would be very misleading. Jews and Christians alike borrowed similarly from those Gentile/Greco-Roman ideas and images, and followed very similar trajectories. Around 400, at least some synagogues were more open to appropriating pagan imagery than were churches – though of course they borrowed them without the explicit pagan connotations. In making that point, I relish the coincidence (and that is all it is) that the best Jewish examples of this story come from Jesus’s homeland, of Galilee.

As so often, it is very difficult to tell the story of early Christianity without getting quite deep into the Judaism of the same era.

Finally, it is also somewhat weird to think of all these artistic extravaganzas specifically in Palestine dating from the third century through the sixth, exactly the key period of the writing and compilation of the Talmud, and specifically the Jerusalem Talmud. Some of the key figures actually worked in centers like Tiberias and Sepphoris. Somehow, I never thought of all those great sages living and working in such a rich world of visual display. My ignorance.