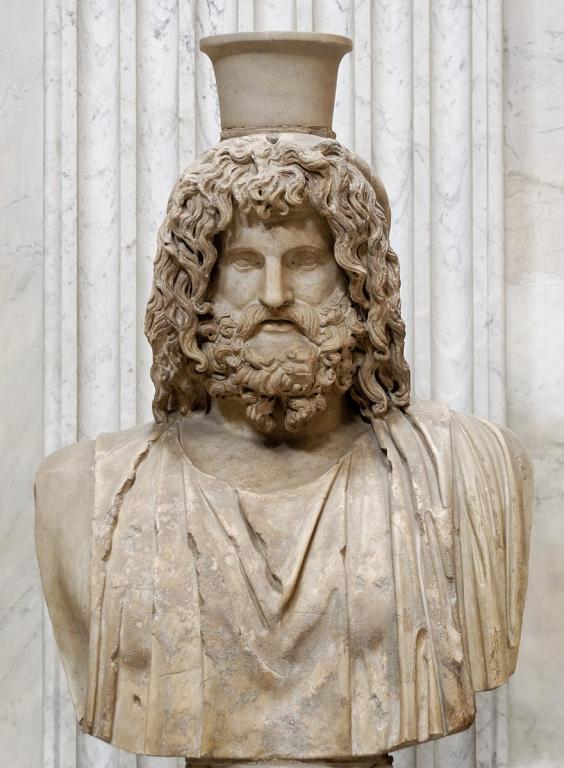

This fine sculpture, from San Francisco’s glorious Asian Art Museum, depicts a bodhisattva, a holy figure of Buddhism, which was made in what is now Afghanistan. Specifically, it depicts the Buddha that is to come, the messianic figure of Maitreya. But note that the style of the depiction borrows massively from Hellenistic Greek techniques and aesthetics. I will suggest that this kind of artistic cross-pollination – this cultural globalization – has a surprising amount to tell us about the history of Judaism in the couple of centuries before Jesus’s time. And specifically, about some might have beens, some roads that were almost taken, if not quite.

I have been writing about the famous Jewish revolt under the Maccabees, in the 160s BC, the event celebrated by Hanukkah. The revolt was directed against Hellenization, which was absolutely not a novelty suddenly dropped on the Jews by the king Antiochus IV. Rather, that Hellenization represented a long term process, which came close to absorbing Judaism into the mainstream pagan culture of the time.

By way of background, the Greeks under Alexander the Great conquered Palestine in the 330s BC, and from then until the 160s, the land was variously under the two great successor empires, the Seleucids of Asia, or the Ptolemies of Egypt. During this time, foreign traditions flowed easily into Jewish culture, enhancing and strengthening it. At the same time, those influences created a reaction and a call to return to older and purer standards. The tension between those two impulses, of accommodation and restriction, is a major part of the history of the Jewish people in this period, as it would be in so many later eras, especially in the post-Enlightenment world.

Jewish elites vigorously debated what aspects of traditional faith and practice might be adjusted or even abandoned in order to promote accommodation, without betraying their fundamental ways. Critically for later concepts of the divine, Jews discovered Greek philosophy during this period, causing an enduring dilemma. Yes, they wanted to absorb the latest forms of cutting-edge sophistication, yet at the same time, Jews resented the loss or contamination of older values. They knew that they must confront and absorb Greek philosophical ideas if they hoped to engage in communication with the educated world, but even so, they had to avoid any connection to pagan deities or anything hinting at polytheism. Those debates, those dilemmas, had a huge impact on early Christianity, and its understandings of Christology.

Two features of Greek culture made the new empires potentially very dangerous to Judaic traditions.

One was cultural inclusiveness. The Greeks, generally, were very open-minded about the cults and religions of the regions in which they settled, and Hellenistic cultures often reimagined local deities in forms more congenial to them. In Egypt the first Ptolemy deliberately created the new Greek-styled cult of Serapis in order to unify the empire’s old and new populations. This new god merged the ancient native cults of Osiris and Apis into a composite figure in the best Greek mode, and he attracted a widespread following. At the same time, the goddess Isis was combined with multiple female Greek deities to construct an all-powerful Queen of Heaven.

Sometimes, such a foreign-derived figure became the centerpiece of one of the Greek mystery religions that were in vogue from the third century BC onward. Such movements took believers through successive levels of initiation and ritual performance in a process that granted them the promise of eternal life and happiness. This all sets the scene for the cults and religious mixings we find in the time of the New Testament, and Paul’s letters.

Beyond their natural syncretism, Greeks also possessed superlative skills of visual representation in sculpture and painting, allowing them to visualize deities according to the extraordinarily high aesthetic standards prevailing at this time. They were superb at making ethnic and regional gods look wholly Greek, as they did with Serapis himself:

It’s not much like what we think of as Egyptian, is it?

In central Asia and on the Indian frontiers, local gods and kings were portrayed in Greek form in statuary and carvings, and this takes us back to the figure at the beginning of this post. While the Greeks occupied Palestine, they also carved out kingdoms in Central Asia and in the lands that we today call Pakistan and Afghanistan. The Bactrian Greek state was followed by the Indo-Greeks. When those empires collapsed politically, Greek ideas and styles remained strong in the successor states run by local peoples. Particularly powerful was the Kushan Empire (1st-4th century AD), which stretched across Pakistan, Adfghanistan and into Central Asia, and which flourished on the astonishing wealth of the Silk Road. As Craig Benjamin remarks, the Kushan state stood “at the crossroads of ancient Eurasia.” The empire had its cultural heart in Gandhara, and the statue illustrated at the top of this post is a Gandharan product.

The Greeks encountered Buddhism in just the same years that it was discovering Judaism, and n both cases, there were complex interactions, and two-way influences. In the mid-third century BC, Buddhist emissaries appeared at both the Seleucid and Ptolemaic imperial courts. One famous Buddhist scripture features a noble patron of the faith called King Milinda, who was actually a Bactrian Greek sovereign called Menander Soter, the Savior. He ruled from ca. 160 to 130 BC, making him a close contemporary of the Maccabean brothers who led the Jewish nationalist revolt. Menander, incidentally, had his capital at yet another Greek-founded city called Alexandria, which we know today as Kandahar, in Afghanistan.

For several centuries, the emerging faith of Mahayana Buddhism represented its bodhisattvas in pure Hellenistic style. Today, scholars study the phenomenon of “Greco-Buddhism,” and specifically Greco-Buddhist art. Do check out that Wikipedia link for a lot of relevant images. The subjects are thoroughly Asian, but the artistic styles are totally Greek, and very fine examples of their kind.

If those cultural pressures were so powerful as far afield as Kandahar and northern India, how much stronger were they for the Mediterranean Jewish community, living amid Greek and pagan neighbors? We know that between about 300 BC and the 160s, Palestine’s Jews agonized over how far they could accept pagan ways. In the early second century, two key men held the high priesthood, and each represented a rival noble faction. Their names, significantly, were Jason and Menelaus – how Greek could you get?

Between them, they engaged in an escalating war of dueling Hellenisms. Jason built a gymnasium, which may not sound too controversial until you realize that this was where men went to exercise gymnos, naked. Jews thus faced the dreadful humiliation of revealing the fact of circumcision, a custom that appalled civilized Greeks. Fortunately, surgical procedures were available to help disguise what was seen as a mutilation. The Jewish elite went further than ever before in adopting Greek clothes and fashions. Priests neglected their services in order to become spectators at contests in wrestling and discus throwing.

In every respect, Jason offered to advance the cause of Hellenization, to bring his people over to the Greek way of life, Hellenikon charaktera. He even proposed to rename his city in proper royal Greek form, as Antioch-in-Jerusalem. When the Seleucid king held games at Tyre, the high priest sent money for sacrifices to Herakles (2 Macc. 4). Although his effort was thwarted, that would have meant a Jewish high priest directly, and unthinkably, sponsoring sacrifices to pagan gods. (Fittingly, Jason eventually died at Sparta).

In such a world, there was a natural temptation to assimilate the Jewish deity to Greek normality, and ultimately to portray YHWH himself with an iconography close to that of Zeus. When pagans actually did penetrate the Holy of Holies—as did the forces of Antiochus IV in the 160s, and the Romans a century later—they were stunned and baffled to find no actual figure of the deity, an absence quite contrary to the religious thought of the day.

As far as we know, nobody actually dared take the step of commemorating YHWH in concrete visual form, but some such move was the logical next step in the Hellenization pushed so hard by Jewish enthusiasts. Perhaps a future statue in the Temple precincts might combine YHWH with one of the gods beloved by the Seleucid kings, such as Apollo or Zeus. Why should YHWH not merge into some new composite divinity who could generate the same broad multi-ethnic appeal as Serapis? The question was not whether there would be a Greco-Judaism, but rather how syncretistic it would become. That would have gone far beyond the generic “Hellenistic Judaism” that we sometimes discuss.

That serves as the context for the now-notorious campaign of Antiochus IV in the 160s, which directly provoked the Maccabean revolt. Antiochus rededicated the Jerusalem Temple to Zeus Olympios (with the Samaritan Temple at Gerizim dedicated to Zeus Xenios, Friend of Strangers). Initially, the king won some successes. Gentile inhabitants had no difficulty sacrificing to particular deities, and many Jews agreed “to build altars and sacred precincts and shrines for idols, to sacrifice swine and unclean animals, and to leave their sons uncircumcised. They were to make themselves abominable by everything unclean and profane” (1 Macc. 1:47). Conceivably, they read the new Temple dedication as not to Zeus as an extraneous foreign deity, but rather to a syncretic form of YHWH, a new form of the old God.

After the successful revolt, the second book of Maccabees (mid-late second century BC) wrote about the foreign ideas as Hellenism, and actually coined a new word to describe the system of beliefs that was under threat: this is the first appearance of the word “Judaism,” Ioudaismos. As so often in the history of religions, a faith described itself more clearly in terms of what it was against, of what was threatening it.

This background also helps us understand why Jewish elites of the first century AD were so extremely nervous about the new Jesus movement and its ideas, which could easily be presented as concessions to pagan belief. The stronger the Greek and Gentile role grew in the church, the greater those dangers to Ioudaismos became.

So I come back to that statue at the start of this post. It intrigues me because we came very close to a world in which Jewish elites started constructing statues to the deity, which would of necessity have been in pure Greek fashion. And these Greco-Buddhist sacred figures, those bodhisattvas, give us a good sense of a visual world that might have been – that lost world of Greco-Judaism.

The Serapis photo is public domain. All other photographs are my own work. All are from the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, except the last, which is from the Kimbell in Fort Worth.