The frenzied commentary around Mark Galli’s Christianity Today editorial has not only revealed widely diverging opinions within the evangelical community about the Trump presidency, but also about about what, if anything, an anti-Trump editorial in the pages of CT portends. Is this merely futile virtue-signaling on the part of a few evangelical elites who are hopelessly out of touch with real evangelicals? Or is this a crack in the dam, unleashing the pent up but until now mostly quiet resistance to Trump among American evangelicals? Or, is this too little, too late from establishment evangelicals who remain blind to the ways in which they themselves have aided and abetted the ideology they now claim to abhor?

Fortunately we have more than opinions to work with in our efforts to answer these questions. In the coming weeks and months, several books will help piece together the puzzle of white evangelical support for Trump and offer American Christians a different way forward.

Four years out from 2016, we’re reaping the literary fruit of a season of disenchantment and reassessment, and 2020 is looking to be a banner year for books at the intersection of religion and American politics.

Our Religious Moment

First off, there are a number of general interest books by scholars and writers that explore aspects of the disruptive religious moment we find ourselves in.

Although technically not a 2020 publication, I’ll start with Chrissy Stroop and Lauren O’Neal’s Empty the Pews: Stories of Leaving the Church, just out with Epiphany Publishing. A leading “exvangelical” voice, Stroop coined the hashtag #EmptyThePews after the 2016 election, and these 21 essays “by those who survived hardline, authoritarian religious ideology and uprooted themselves from the reality-averse churches that ultimately failed to contain their spirits” offer a deeply personal engagement with conservative faith traditions that participants and observers of evangelicalism, Catholicism, and Mormonism will find illuminating and, undoubtedly, provocative.

I had the privilege of reading an advance reading copy of Ruth Everhart’s The #MeToo Reckoning: Facing the Church’s Complicity in Sexual Abuse and Misconduct (IVP, also just out), and here’s what I had t o say: “This is a book for survivors, for churches who have failed victims, for those who seek to mourn with those who mourn, and for those who love justice and endeavor to bring healing and renewal. By weaving together biblical narratives and contemporary stories with her own painful past, Ruth Everhart unflinchingly confronts the culture of silence, shame, and denial that too often characterizes a Christian response to abuse. This is a book of reckoning.”

o say: “This is a book for survivors, for churches who have failed victims, for those who seek to mourn with those who mourn, and for those who love justice and endeavor to bring healing and renewal. By weaving together biblical narratives and contemporary stories with her own painful past, Ruth Everhart unflinchingly confronts the culture of silence, shame, and denial that too often characterizes a Christian response to abuse. This is a book of reckoning.”

Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove, too, has a new book just out, Revolution in Values: Reclaiming Public Faith for the Common Good (IVP), in which he confronts Christians who have “misused Scripture to consolidate power, stoke fears, and defend against enemies,” and offers instead stories that help Christians “rediscover hope for faithful public witness that serves the common good.”

Another timely contribution to the life of the church, Chuck DeGroat’s When Narcissism Comes to Church: Healing Your Community from Emotional and Spiritual Abuse, will be published with IVP this March. Calling out abuse of power in ministry and in church systems is key, but DeGroat goes beyond this to offer steps for repentance and healing. As such, it will serve as an important resource for many churches striving to address abusive systems they are only beginning to identify.

Michael Austin’s God and Guns in America (Eerdmans, May 12), meanwhile, sets its sites on the issue of gun control, asking the question: “What would it look like for Christians to go beyond thoughts and prayers in their response to gun violence?”

Jessica Goudeau’s After the Last Border: Two Families and the Story of Refuge in America (Viking, April 28) offers an intimate look at the lives of two refugee women—a Christian from Myanmar and a Muslim from Syria—both trying to struggle for the American dream. Goudeau situates this “dramatic, character-driven story within a larger history—the evolution of modern refugee resettlement in the United States, beginning with World War II and ending with current closed-door policies.” If Goudeau’s previous writing is any sign, it will be a beautifully crafted and deeply probing narrative.

Two other books address the state of American Christianity directly. D. L. Mayfield’s The Myth of the American Dream: Reflections on Affluence, Autonomy, Safety, and Power (IVP, April 14) is, in the words of Ron Sider, “a wonderful mix of captivating personal experiences, biblical teaching, and probing structural analysis,” a challenge to American Christians to rethink Jesus’ command to love our neighbor as ourselves. David Gushee’s After Evangelicalism (Westminster John Knox, August) offers a guide to those disenchanted by the current iteration of conservative evangelicalism but unwilling to empty the pews—to those seeking a religious path forward beyond the ruins of a deconstructed tradition.

Two other books address the state of American Christianity directly. D. L. Mayfield’s The Myth of the American Dream: Reflections on Affluence, Autonomy, Safety, and Power (IVP, April 14) is, in the words of Ron Sider, “a wonderful mix of captivating personal experiences, biblical teaching, and probing structural analysis,” a challenge to American Christians to rethink Jesus’ command to love our neighbor as ourselves. David Gushee’s After Evangelicalism (Westminster John Knox, August) offers a guide to those disenchanted by the current iteration of conservative evangelicalism but unwilling to empty the pews—to those seeking a religious path forward beyond the ruins of a deconstructed tradition.

Religious But Not Conservative

In light of 2016, much ink has been spilled analyzing, critiquing, and deconstructing conservative religious traditions. This is not about to end (see below). But focusing on conservative religion to the neglect of progressive traditions may end up serving as a self-fulfilling prophecy. L. Benjamin Rolsky’s The Rise and Fall of t he Religious Left: Politics, Television, and Popular Culture in the 1970s and Beyond (Columbia, October 2019) offers a fascinating cultural study of the religious left. In the coming months, two more books will help swing the conversation to progressive faith traditions and their role in American culture and politics. Jack Jenkins (RNS) is known for his sharp reporting on American religion and for his coverage of progressive Christianity, and his American Prophets: The Religious Roots of Progressive Politics and the Ongoing Fight for the Soul of the Country will be out in April with HarperOne. In September, activist and writer Guthrie Graves-Fitzsimmons’ Just Faith: Reclaiming Progressive Christianity will release with Fortress Press.

he Religious Left: Politics, Television, and Popular Culture in the 1970s and Beyond (Columbia, October 2019) offers a fascinating cultural study of the religious left. In the coming months, two more books will help swing the conversation to progressive faith traditions and their role in American culture and politics. Jack Jenkins (RNS) is known for his sharp reporting on American religion and for his coverage of progressive Christianity, and his American Prophets: The Religious Roots of Progressive Politics and the Ongoing Fight for the Soul of the Country will be out in April with HarperOne. In September, activist and writer Guthrie Graves-Fitzsimmons’ Just Faith: Reclaiming Progressive Christianity will release with Fortress Press.

White Evangelicals/Christian Nationalism

Still, white evangelicalism remains a topic of fruitful exploration. One book that provides essential background on the history of American evangelicalism is Daniel Vaca’s Evangelicals Incorporated: Books and the Business of Religion in America, published earlier this month by Harvard University Press. Defining evangelicalism as a commercial religion, Vaca offers a fascinating history of evangelical publishing from the 19th century to the present: “Vaca not only illustrates how evangelical ideas, identities, and alliances have developed through commercial activity but also reveals how the production of evangelical identity became a component of modern capitalism.” It’s also a great read that helps make sense of much of the last century of American evangelicalism.

Several key books are also poised to engage evangelical support for Trump more directly. Releasing in the coming days and months, these books address head-on the questions Galli’s editorial raises.

Releasing this week, Gerardo Martí’s American Blindspot: Race, Class, Religion, and the Trump Presidency (Rowman & Littlefield) offers a retrospective on white evangelical support for Trump. I had the privilege of reading an advance copy of Martí’s book, too, and here’s what I had to say: “Martí makes a compelling case that th e election of Donald Trump should not have come as a surprise. Drawing on expansive historical and sociological evidence, he demonstrates that support for Trump reflects longstanding patterns of behavior and deeply entrenched commitments.”

e election of Donald Trump should not have come as a surprise. Drawing on expansive historical and sociological evidence, he demonstrates that support for Trump reflects longstanding patterns of behavior and deeply entrenched commitments.”

Another highly anticipated sociological take on conservative religious support for Trump is Andrew L. Whitehead and Samuel L. Perry’s Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States (OUP, March 2). Whitehead and Perry have already produced incisive articles disclosing the centrality of Christian nationalism in driving partisan loyalties. As “the first comprehensive empirical analysis of Christian nationalism in the United States,” this book will define the conversation going forward.

As will the next two books: Katherine Stewart’s The Power Worshippers: Inside the Dangerous Rise of Religious Nationalism (Bloomsbury, March 3) and Sarah Posner’s Unholy: Why White Evangelicals Worship at the Altar of Donald Trump (Random House, May 26). Stewart’s book decenters social and cultural issues to present the Religious Right as a dangerous movement “waging a political war on the norms and institutions of American democracy.” It is a book that “demands that Christian nationalism be taken seriously as a significant threat to the American republic and our democratic freedoms.” Posner’s Unholy provides a similarly grim picture of conservative Christianity, revealing how “race and xenophobia have always been at the movement’s core, and how religion has been used to cloak anxieties about perceived threats to a white, Christian America.”

As will the next two books: Katherine Stewart’s The Power Worshippers: Inside the Dangerous Rise of Religious Nationalism (Bloomsbury, March 3) and Sarah Posner’s Unholy: Why White Evangelicals Worship at the Altar of Donald Trump (Random House, May 26). Stewart’s book decenters social and cultural issues to present the Religious Right as a dangerous movement “waging a political war on the norms and institutions of American democracy.” It is a book that “demands that Christian nationalism be taken seriously as a significant threat to the American republic and our democratic freedoms.” Posner’s Unholy provides a similarly grim picture of conservative Christianity, revealing how “race and xenophobia have always been at the movement’s core, and how religion has been used to cloak anxieties about perceived threats to a white, Christian America.”

At this point, I think a word is in order regarding the historiography of American evangelicalism. Until recently, there has been a gap in the literature between popular histories of conservative evangelicalism—books like Michelle Goldberg’s Kingdom Coming: The Rise of Christian Nationalism, Jeff Sharlet’s The Family: The Secret Fundamentalism at the Heart of American Power, and Chris Hedges’ American Fascists: The Christian Right and the War on America—and academic studies of evangelicalism such as George Marsden’s Fundamentalism and American Culture or Molly Worthen’s Apostles of Reason. I think a couple of factors contributed to this gap.

Within the field of religious history, scholars worked to understand religious actors on their own terms and resisted casting aspersions on religious traditions. This was due in part to the influence of methodologies borrowed from ethnography and cultural studies more generally, and it served to distinguish religious history from the occasional sloppy (and disparaging) journalistic account of conservative faith traditions. But this gap was also due in part to the prevalence of evangelicals themselves in the field of American religious history. Many evangelicals writing the histories of evangelicalism still identified with the movement, and many were positioned in a way that enabled them to see the more noble traits of their intellectual and religious tradition while remaining largely shielded from the darker underbelly of the same.

With 2016, the dark underbelly became impossible to ignore, prompting a number of observers—and many evangelicals themselves—to reassess the history of the movement they thought they knew.

A number of books are now poised to bridge this gap. John W. Compton’s The End of Empathy: Why White Protestants Stopped Loving Their Neighbors (OUP, June 1) examines how conservative evangelicals came to oppose government efforts “to promote a more equitable distribution of wealth and political authority.” Lauren Kerby’s Saving History: How White Evangelicals Tour the Nation’s Capital and Redeem a Christian America (UNC, April 13) explores the fascinating world of Christian heritage tourism. And Paul Matzko’s The Radio Right: How a Band of Broadcasters Took on the Federal Government and Built the Modern Conservative Movement (OUP, May 1) traces the history of media echo chambers by telling the story of conservative radio—a story in which fundamentalist Christians played a leading role.

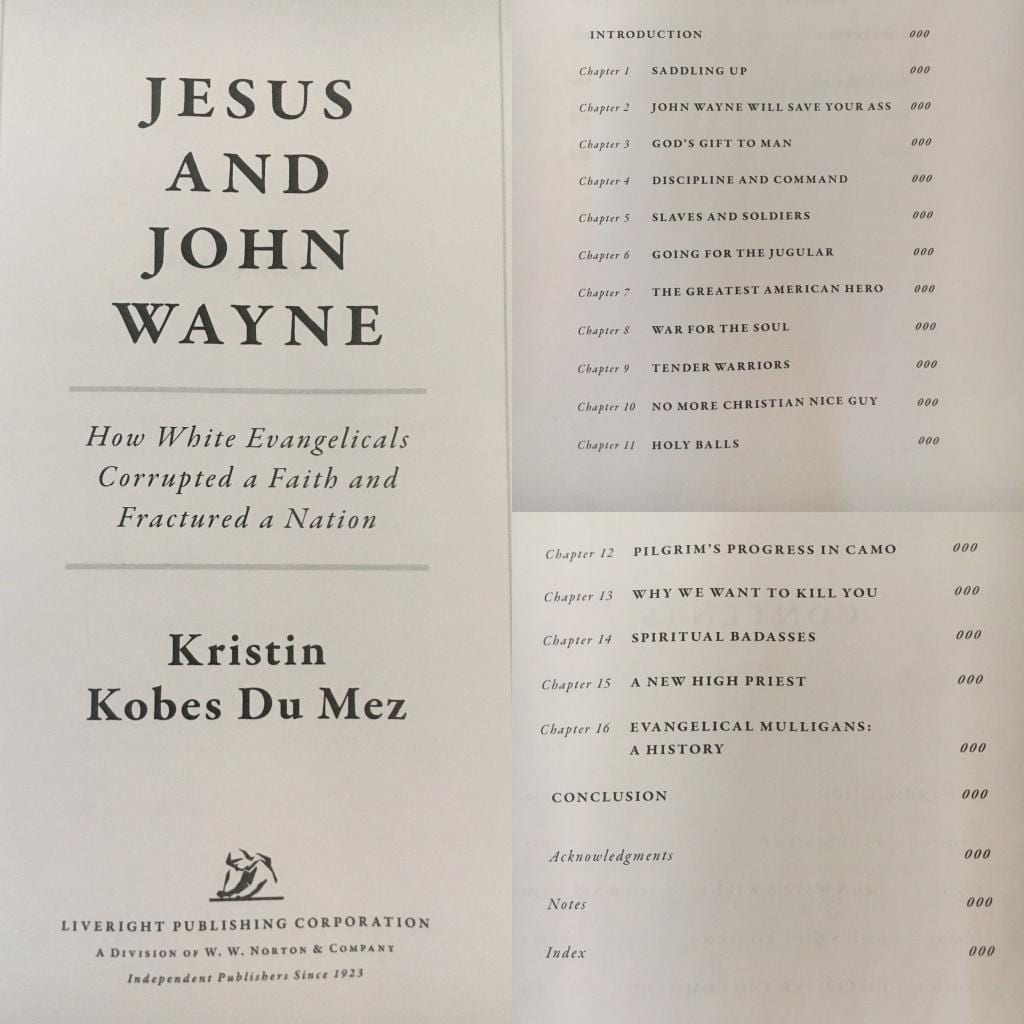

My own Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation (June 23) fits into this category as well.  As the chapter titles attest, the book offers an entertaining and at times startling examination of evangelical popular culture and politics, revealing how a commitment to white patriarchal authority wielded in defense of Christian nationalism resides at the heart of American evangelical identity. It traces how a Christian warrior masculinity inspired culture warriors at home and an aggressive foreign policy abroad, finding expression in a celebration of guns and law enforcement of strong men and strong walls, authoritarian leadership, and the belief that the ends justify any means. Although critics like to decry the hypocrisy of evangelicals who support Trump, Jesus and John Wayne makes clear that the affinities run deep. Moreover, these affinities bind together the “respectable” and extreme corners of evangelicalism far more securely than many establishment evangelicals would care to admit. With a cast of characters ranging from Oliver North, Mel Gibson, and the Duck Dynasty clan to Eric Metaxas, John Piper, and James Dobson, the book refuses to distinguish evangelicalism as a cultural and political movement from a more proper, theological tradition. Instead, it examines the networks and alliances that define evangelicalism today as a God-and-country faith—as a cultural, religious, and political movement.

As the chapter titles attest, the book offers an entertaining and at times startling examination of evangelical popular culture and politics, revealing how a commitment to white patriarchal authority wielded in defense of Christian nationalism resides at the heart of American evangelical identity. It traces how a Christian warrior masculinity inspired culture warriors at home and an aggressive foreign policy abroad, finding expression in a celebration of guns and law enforcement of strong men and strong walls, authoritarian leadership, and the belief that the ends justify any means. Although critics like to decry the hypocrisy of evangelicals who support Trump, Jesus and John Wayne makes clear that the affinities run deep. Moreover, these affinities bind together the “respectable” and extreme corners of evangelicalism far more securely than many establishment evangelicals would care to admit. With a cast of characters ranging from Oliver North, Mel Gibson, and the Duck Dynasty clan to Eric Metaxas, John Piper, and James Dobson, the book refuses to distinguish evangelicalism as a cultural and political movement from a more proper, theological tradition. Instead, it examines the networks and alliances that define evangelicalism today as a God-and-country faith—as a cultural, religious, and political movement.

Evangelicals in Global Context

American evangelicals, meanwhile, like to point to the fact that evangelicalism exists beyond American borders. Even so, American evangelical influence transcends those borders. Two highly anticipated books will provide critical insight into evangelical global engagement: David Swartz’s Facing West: American Evangelicals in an Age of World Christianity (OUP, April) and Lauren Turek’s To Bring the Good News to All Nations: Evangelical Influence on Human Rights and U.S. Foreign Relations (Cornell, May). Both promise to be essential reading.

A few more suggestions…

After a bit of a lull early in the year, the Eerdmans religious biography series comes back strong with Doug Foster on Alexander Campbell in June, followed by Paul Harvey on Howard Thurman, Arlin Migliazzo on Henrietta Mears, and Catharine Randall on Gerard Manley Hopkins. Having had an early look at Migliazzo’s book on Mears, I’m particularly interested in how attention to Mears refines our understanding of twentieth-century American evangelicalism.

Finally, a shoutout to forthcoming books from my fellow Anxious Bench bloggers. In addition to David Swartz’s Facing West, look for Philip Jenkins’ Fertility and Faith: The Demographic Revolution and the Transformation of World Religions (Baylor), Tal Howard’s The Idea of Tradition in the Late Modern World (Cascade), and Agnes Howard’s Showing: What Pregnancy Tells Us about Being Human (Eerdmans).

Timed to the 400th anniversary of the Plymouth Colony, John G. Turner’s They Knew They Were Pilgrims: Plymouth Colony and the Contest for American Liberty (Yale, April ) will help ensure that our commemorations are historically accurate. The story he tells is neither of otherworldly saints nor extraordinary sinners, but one that is “entertaining, erudite, and wonderfully human.”

*Even as I write this, I am acutely aware that this list will inevitably be missing other essential reads. Please add additional books you’re looking forward to (including your own!) in the comments section below.