We’re pleased to welcome Jackie Den Hartog to the Anxious Bench. Jackie holds a Ph.D. in English from the University of Notre Dame and enjoys teaching literature to students of many ages. She lives in Birmingham, Alabama, with her husband and four children.

***

As a parent, one of the hard things about explaining the current pandemic—and the prescribed course of social distancing—to our children is that they don’t really have a frame of reference for it. They don’t have any historical understanding of the concept of “quarantine” because vaccines have made the threat of highly communicable diseases irrelevant to their daily lives. This past week I was reminded again how historically anomalous it is for children to live without the threat of life-threatening contagious diseases, and how recently in our own country’s educational history children were taught to understand and appropriately respond to these diseases.

In our basement we have a handful of old grade-school health textbooks from the 1940s and 50s, discards from the grade school I attended but used decades before my time. My kindergarten daughter enjoys the stories and pictures, so we’ve been using two of them for her reading practice. Entitled Three Friends and Five in the Family, these volumes were published by Scott, Foresman and Company in 1948 as part of their Health and Personal Development Series and were widely used in grade schools across the United States. The stories follow several children through everyday adventures and incorporate lessons about hygiene, health, safety, and personal responsibility. The families and fashions depicted reflect the mores of post-war America, but the portrayal of quarantine could not be more relevant given the rapid spread of COVID-19 and the upheaval of daily life we are all experiencing.

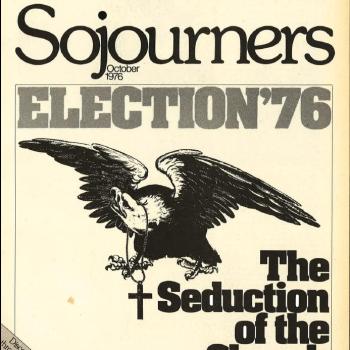

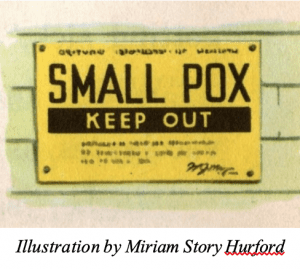

In Three Friends, Sue gets sick and shortly thereafter is quarantined at home with her mother. Even her father and siblings must leave because “A man came and put something red on the house. After that no one could go in or out.” The illustration shows a local health official nailing a bright red sign emblazoned with the words “Scarlet Fever” to the house.

In Three Friends, Sue gets sick and shortly thereafter is quarantined at home with her mother. Even her father and siblings must leave because “A man came and put something red on the house. After that no one could go in or out.” The illustration shows a local health official nailing a bright red sign emblazoned with the words “Scarlet Fever” to the house.

The story goes on to describe how Sue was “very, very sick” for a long time and could not play with her friends or see anyone. The description of her days in bed would probably have resonated with children (and parents) in the reading audience, since scarlet fever was still a leading cause of childhood death in the early 20th century. Eventually Sue does recover and wants to return to school for a Valentine’s party: “’I am not very sick now,’ Sue said. ‘Why can’t the man come and take down that old red thing? I don’t like to be sick.’” Her mother responds, “No one likes to be sick…That is why you must not play with your friends.” The implication is clear: Sue is not kept inside for her own health and well-being, but for the health of the entire community. The text is gently teaching children to place community wellness about their own desires.

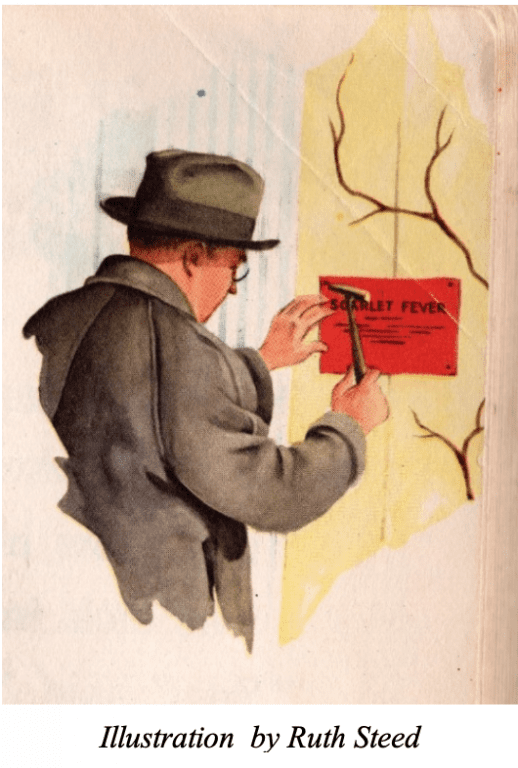

I’ve thought about this story quite a bit in the past few days. As recently as the middle of the twentieth century, children were taught that when they were very sick it was their responsibility to stay home. Whereas today reporting agencies rarely specify the origins of infection much below the county level, in the late 1940s houses were still physically marked in order to precisely indicate the locus of disease. When the quarantine sign went up, everyone in the community understood that it was in their best interest to stay away. In Five in the Family, which follows Three Friends, Mother comes home and tells Father about the signs she has seen on some houses in town. Lest there be any confusion among the reading audience, the textbook continues by saying it was “a yellow sign that looked like this.” Father is understandably concerned and asks whether any of his children went into those houses. “’Oh, no!’ Mother said. ‘They know better than that.’” Clearly, by the time children were about eight years old they were expected to be familiar with signs warning of communicable disease, as well as the social distancing procedures necessary to keep those diseases from spreading.

I’ve thought about this story quite a bit in the past few days. As recently as the middle of the twentieth century, children were taught that when they were very sick it was their responsibility to stay home. Whereas today reporting agencies rarely specify the origins of infection much below the county level, in the late 1940s houses were still physically marked in order to precisely indicate the locus of disease. When the quarantine sign went up, everyone in the community understood that it was in their best interest to stay away. In Five in the Family, which follows Three Friends, Mother comes home and tells Father about the signs she has seen on some houses in town. Lest there be any confusion among the reading audience, the textbook continues by saying it was “a yellow sign that looked like this.” Father is understandably concerned and asks whether any of his children went into those houses. “’Oh, no!’ Mother said. ‘They know better than that.’” Clearly, by the time children were about eight years old they were expected to be familiar with signs warning of communicable disease, as well as the social distancing procedures necessary to keep those diseases from spreading.

Interestingly, Five in the Family also points to the medical advances that would largely eliminate the quarantine system within the next few decades. Mother goes on to tell Father that she has already made an appointment with the doctor for all the children to be re-vaccinated that very evening. Clearly community spread is again recognized as a potential problem, but in this textbook the responsible course of action is to get a vaccine. The message promulgated in health textbooks such as these worked; as a result of widespread vaccination, smallpox was eradicated from North America in 1952. Vaccination against common childhood illnesses became common in the 1960s, as did the use of antibiotics to kill the streptococcus bacteria that causes scarlet fever.

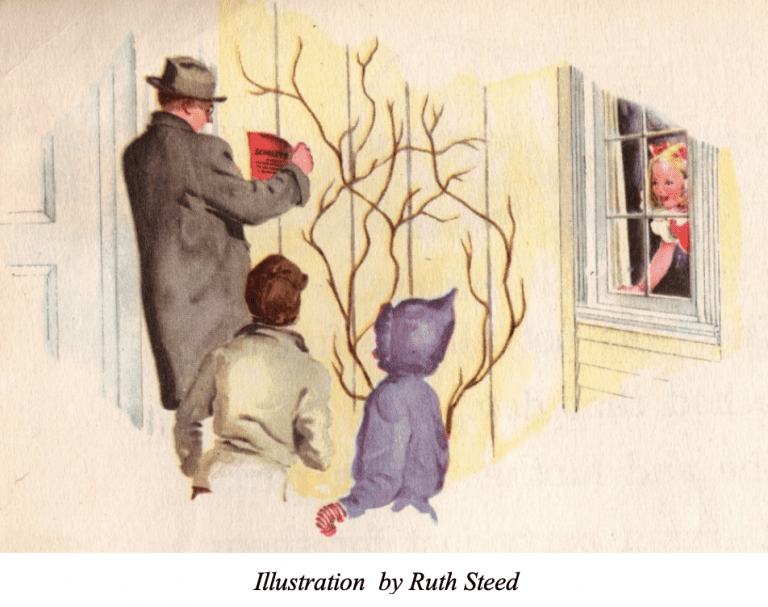

Upon reflection, I’ve realized that although these stories were primarily intended to teach about health, they also gently work to inculcate empathy. When Sue’s friends learn she is ill, they send Valentine’s cards and call her on the phone. Her class chooses to postpone their Valentine’s party until she can return, and the next chapter, entitled “A Welcome for Sue,” shows Sue watching from her window as the public health officer removes the red sign. Behind the officer stand her two friends, waiting for her to come out and play. The suggestion is that the sign does not confer any lasting stigma; it is a public necessity and everyone celebrates when it comes down. The chapter ends with Sue’s class welcoming her back to school.

Upon reflection, I’ve realized that although these stories were primarily intended to teach about health, they also gently work to inculcate empathy. When Sue’s friends learn she is ill, they send Valentine’s cards and call her on the phone. Her class chooses to postpone their Valentine’s party until she can return, and the next chapter, entitled “A Welcome for Sue,” shows Sue watching from her window as the public health officer removes the red sign. Behind the officer stand her two friends, waiting for her to come out and play. The suggestion is that the sign does not confer any lasting stigma; it is a public necessity and everyone celebrates when it comes down. The chapter ends with Sue’s class welcoming her back to school.

I know all too well that teaching empathy to children is difficult; repeated remonstrances to “Be Kind” just aren’t that effective. One silver lining found in the long afternoons now bereft of extracurricular activities is that my children have started to make connections between their own situation and historical events they have previously studied. For the first time they are identifying, albeit in small ways, with American children in previous generations. The empty bread aisle at Aldi prompted discussions of bread lines during the Great Depression, while a half-serious conversation about conserving toilet paper brought to mind the ration books they had seen in a WWII exhibit at the history museum. My hope is that this fledgling historical empathy, and the knowledge that they are not the only children to live through pandemics and quarantines, will lead to greater empathy in the present. I hope that when COVID-19 subsides, they will have a renewed sense of gratitude for the many opportunities and conveniences they have, recognizing that in the not-so-distant past quarantine was endured without Chromebooks and wi-fi. In the meantime, like Sue’s mother, I will gently remind them of the reason they cannot go anywhere: No one likes to be sick.