Will the COVID-19 pandemic be a turning point in the history of Christianity and other religions? In a recent post, Philip was skeptical of the notion that we might see a new religious revival coming out of these last weeks and months, but he did think it possible that we’d look back see how “the crisis massively accelerated a series of trends that were under way,” perhaps even inaugurating a “new normal” for religion.

If the spread of this coronavirus — and the political, economic, social, and cultural responses to it — do reshape faith and worship, it won’t be the first time that a non-religious event has profoundly affected religion.

In his popular survey of “critical turning points” in the history of Christianity, Mark Noll focused on moments when Christian belief and practice were fiercely debated (e.g., the Councils of Nicea and Chalcedon, the Great Schism of the 11th century) or when individual religious experience led to larger revival (e.g., Ignatius founding the Jesuits; the conversions of the Wesley brothers). But he also included a few turning points that had religious effects, but were arguably more about politics than faith, such as the Roman siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE and the French Revolution.

In his popular survey of “critical turning points” in the history of Christianity, Mark Noll focused on moments when Christian belief and practice were fiercely debated (e.g., the Councils of Nicea and Chalcedon, the Great Schism of the 11th century) or when individual religious experience led to larger revival (e.g., Ignatius founding the Jesuits; the conversions of the Wesley brothers). But he also included a few turning points that had religious effects, but were arguably more about politics than faith, such as the Roman siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE and the French Revolution.

It’s far too early to know if COVID-19 will enter a future edition of such a book, but I asked colleagues here at The Anxious Bench to join me in nominating other non-religious turning points in religious history, both in this country and beyond it.

Tomorrow we’ll look at four turning points from the 20th century. But first, three from the years before 1900. This isn’t meant to be an exhaustive list, and we’re obviously missing some key moments. So please feel free to nominate other events in the comments section!

The Black Death

The first time I taught medieval European history, I had 18 students in my class. One day I asked them all to stand up. It was 1346, I told them. The year an age-old disease resurfaced, becoming a new super-killer that spread around the globe. I told ten students to sit down because, according to medieval records, they were now all dead. The remaining 8 students just looked at each other—they were now all who were left to carry on the medieval world. Katherine French quotes The Eulogium, a monastic chronicle from Wiltshire in England, in her book The Good Women of the Parish: “By the time the plague ceased at the divine command, it had caused such a shortage of servants that men could not be found to work the land, and women and children had to be used to drive plows and carts, which was unheard of.” Indeed, evidence tells us that within less than ten years, between 1346 and 1353, 40-60% of all the people living in Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa died from what we now call the Black Death. Medieval people knew it as the Great Pestilence, or simply the plague. As Monica H. Green writes, “the mortality caused by the Black Death is the highest of any large-scale catastrophe known to humankind, save for the impact of smallpox and measles on indigenous peoples in first-contact events of the early modern period.” The Black Death changed the world—especially since it kept returning, decade after decade.

Did you know it also changed the medieval church? The clergy died in even higher numbers than ordinary people because they were doing their job—administering last rites and taking care of the spiritual needs of their terrified parishioners. But this caused a serious crisis for the medieval church. There were simply not enough priests to take care of the medieval population, which was especially bad since medieval people needed the sacraments for salvation. So guess what? The medieval church responded pragmatically, lowering educational standards in an attempt to bolster clerical recruitment and encouraging more lay participation in the church itself. French has charted an increase in women’s activity in the late medieval church, arguing that the social upheaval following the Black Death helped open up a space of authority for women in late medieval English churches. (As I recently wrote in my article “Medieval Sermons and Audience Appeal After the Black Death.”) Women, in other words, became more visible and active in late medieval Christianity in the aftermath of a global pandemic. (Beth Allison Barr)

1675-1685

Throughout history, climate-driven catastrophes have repeatedly transformed human affairs, bringing famine and plague, which in turn caused scapegoating and mass migration, rebellion and war. During the long period of the Little Ice Age, the coldest era was in the years from roughly 1675 through 1685, with all the social miseries that would imply.

The religious consequences were immense, and lasting. Apocalyptic visions drove new religious movements, including (in its opening years) Pietism. Rebellions and persecutions drove many exiles around the world, but especially to the Americas: Baptists, Quakers, Huguenots, and many others. All followed the words made famous in John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (1678), “Flee from the wrath to come.” Under bitter persecution, Scots Presbyterians evolved the field preaching traditions that would later develop into American frontier camp meetings. Welcoming exiles, the new colony of Pennsylvania (1682) enacted radical new ideas of religious liberty. In Continental Europe, persecutions and rebellions ignited the wars that culminated in the siege of Vienna (1683), which decisively reversed Islamic advances, and paved the way for the Christian reconquest of south-eastern Europe. The climate shock birthed a new religious world. (Philip Jenkins)

Chicago’s Columbian Exposition of 1893

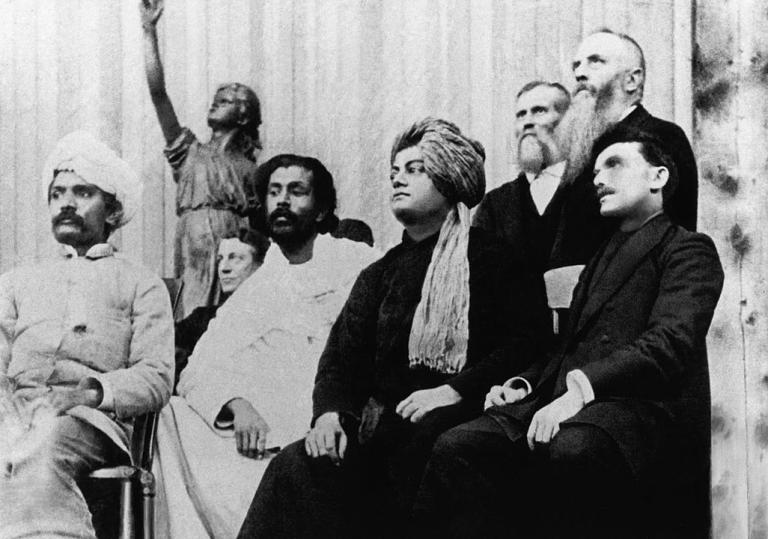

In the tradition of the grand world fairs of the nineteenth century that had previously taken place in cities such as London and Paris, Chicago’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 was intended as an opportunity for the young United States to show off its industrial prowess to other nations on the occasion of the fourth centenary of Columbus’s voyages to the New World. (Planning delays kept it from taking place in 1892 when it was originally scheduled.) As preparations got underway, two Chicagoans, the Theosophist Charles Carroll Bonney and the Presbyterian minister John Henry Barrows, alighted on the idea to use the event as an excuse to hold the first-ever World’s Parliament of Religions and invite representatives from major religious traditions to a conference while the Exposition was taking place. After various twists and turns, their idea became a reality: the Parliament opened its doors on 11 September and lasted until 21 September 1893.

The Windy City welcomed Buddhists, Taoists, Zoroastrians, Jains, along with Christians and Jews of various persuasions, among others. An Indian delegate, Swami Vivekananda, riveted the audience with his call for religious tolerance and an end to fanaticism. Several thousands attendees came to hear what for a nineteenth-century American audience were very exotic religious viewpoints. The scholar of comparative religion Friedrich Max Müller wrote of the event: “Such a gathering of representatives of the principal religions of the world has never before taken place; it is unique, it is unprecedented; nay we may truly add, it could hardly have been conceived before our own time.” Historical retrospection largely corroborates Müller’s judgment and the event—something of an afterthought to counterbalance the industrial and economic emphases of the Exposition—is now regarded as a watershed moment in American religious history, inaugurating the practice of interfaith dialogue and serving as a harbinger of the more religiously pluralistic nation of the early twenty-first century. (Tal Howard)