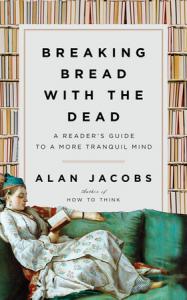

Alan Jacobs writes books with pretentious titles. How to Think. I didn’t know what to think about that when I first saw it. The Pleasures of Reading. It was a pleasure. Original Sin. A guilty pleasure.

I’ve been hoping that Jacobs would write How to Write, which I then could apply to my own projects. Instead, Jacobs has given us Breaking Bread with the Dead. It’s tasty.

“What brings tranquility?” asks Jacobs through the words of Horace translated by David Ferry. That’s the first question that animates this book. Jacobs begins with the almost unavoidable twenty-first-century habit of checking one’s email and apps constantly. In the car, on the toilet, in class, while students take a brief quiz. Everyone’s distracted. And anxious. And people are angry about politics and the pandemic and protests. And the more time we spend trolling our perceived enemies online or cheering on the anger of our perceived allies, the more distracted and anxious and angry we become.

“What brings tranquility?” asks Jacobs through the words of Horace translated by David Ferry. That’s the first question that animates this book. Jacobs begins with the almost unavoidable twenty-first-century habit of checking one’s email and apps constantly. In the car, on the toilet, in class, while students take a brief quiz. Everyone’s distracted. And anxious. And people are angry about politics and the pandemic and protests. And the more time we spend trolling our perceived enemies online or cheering on the anger of our perceived allies, the more distracted and anxious and angry we become.

Second question: how do we get beyond our own narrow, self-centered selves? Jacobs puts it in more elegant terms. Many of us are trapped by presentism and limited bandwidth. We need more “personal density,” as a character in Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow put it. One result is that we cannot handle people who see the world differently than we do or who reach different conclusions about politics or the pandemic. When we are rooted narrowly in our own space and time, we cannot weather the storms and chaos of the world.

Jacobs’s solution comes from a line by W.H. Auden: “Art is our chief means of breaking bread with the dead.” Jacobs tells anxious, frenetic, and self-centered moderns that they should be “sitting at table with our ancestors and learning to know them in their difference from, as well as their likeness to, us.”

Not only does Jacobs think we need history, he even provides good reasons why we benefit from a deep and thoughtful engagement with the past. No silly platitudes about studying the past to avoid its mistakes. Instead, Jacobs suggests the study of the past will increase your personal density. Don’t worry. Although it is a sedentary activity, Jacobs does not mean that breaking bread with the dead will increase your waistline.

Jacobs is not recommending we encounter the past through a shelf of hot-off-the-press university-press monographs. Far better are old and great books that introduce us to fascinating and sometimes perplexing men and women. Jacobs wants us to break bread with those who lived before us and treat them “not as others but as neighbors – and then, ultimately, as kin.” That requires considerable forbearance and a large dollop of generosity. Some of these meals will be downright uncomfortable. For instance, Jacobs references a student who refused to read Edith Wharton because of her anti-Semitism. Jacobs empathizes with the student’s repulsion. And of course, since the dead at our table are, well, dead, we can always break off the conversation. But that’s a good reason to hang in there, because engaging the past is an especially safe way to encounter difference and even repugnance. For example, Frederick Douglass displayed an “almost ostentatious fairmindedness” toward the founders, concluding that they – like Noah according to some rabbis – were “great in their day and generation.”

John Fea makes a similar argument in his trenchant Why Study History. When we move beyond presentism and our desire to manipulate the past for our own purposes, we inculcate humility. Ideally, as Jacobs puts it, we acknowledge that even when past figures “go far astray they do so in ways that we surely would have, had we been formed as they were.” As we understand past figures on their own terms, as we realize the ways in which they are at once like and unlike us, we become less trapped in the present. We receive a rich lesson in human frailty and possibility.

There are obvious limits to this generosity. The past includes moral monsters. I might have some academic reasons for studying Goebbels, but I’d rather not break bread with him. Most of the flawed figures of the past, however, are not moral monsters. They are just human beings living in circumstances different from our own.

It is impossible to read Breaking Bread without reference to the “cancel culture” of contemporary wokeness. Surely Jacobs would have no patience for individuals who haven’t read Flannery O’Connor demanding that a Catholic university remove her name from a residence hall. And less for the university’s capitulation to such silliness. It’s not that we have to maintain all of the ways we honor the flawed figures of the past. Goodbye, Confederate statues. And Jacobs wouldn’t have faulted Frederick Douglass had he simply loathed the Founders. The problem is that it’s very difficult to find sinless women and men to venerate. We should tread more carefully. And read O’Connor.

Reading Alan Jacobs makes me feel tranquil. He is the master of the pithy example and quotation. (If you like Jacobs’s prescription but aren’t sure where to start, just look through his footnotes). Furthermore, he’s affirming my vocation. I spend a lot of time breaking bread with the dead, not least because I snack constantly while I read and work. But, yes, I do feel enriched by reading books I love again and again, from Augustine’s Confessions to William Bradford’s History to Douglass’s autobiography to Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead.

Still, I have my doubts, not about the value of studying the past, but because I don’t think breaking bread with the dead delivers as much as Jacobs promises. The trouble is that one can still spend a lot of time with the past and still live wretchedly in the present, even if one follows Jacobs’s advice about how to engage the dead. Anyone in the humanities knows people with a keen sensitivity toward their historical subjects and an utter lack thereof toward their students and colleagues. And one can enjoy the tranquility of books for a few hours – a blessed respite, no doubt – and then resume a life of distraction, anxiety, and anger.

Do I think my decades-long engagement with past has increased my personal density? Sometimes. But I’m also ensconced in academia, in suburbia, and a pretty homogeneous church. Sitting in my study reading old books only gets me so far, as much as I love it.

Others things have increased my personal density much more. Marriage and fatherhood are tops on my list. Living in different places, in the U.S. and abroad, also has disrupted parochial tendencies. Jacobs is correct that even more so than the present, the past “brings home to us in distinctive ways the enormous range of difference in human experience.” But there’s hardly a shortage of living human diversity, even within my academic building, suburb, and church. The most quotidian human encounters can also increase one’s “personal bandwidth.” Furthermore, there is also no shortage of people who live well in the present without the old books Jacobs and I love.

Jacobs doesn’t exactly say that studying the past is more important than cultivating relationships with the living. Still, he’s a bit over-exuberant about the dead. Our personal density hinges so much more on those living relationships: with our families, our friends, our neighbors, our colleagues, and our fellow congregants. And as Christians, the most important way we break bread with the dead is through the Eucharist, the Lord’s Supper, where, surrounded by a great cloud of witnesses, we get a foretaste of the heavenly banquet of our Lord.

So yes, check your email less often. Ignore the live update on today’s crisis, by all means. The world will still be a mess when you get back to it. And, certainly, break bread with the dead in a Jacobsian spirit of generosity. Tranquility, increased personal density, and thicker temporal bandwidth may result.