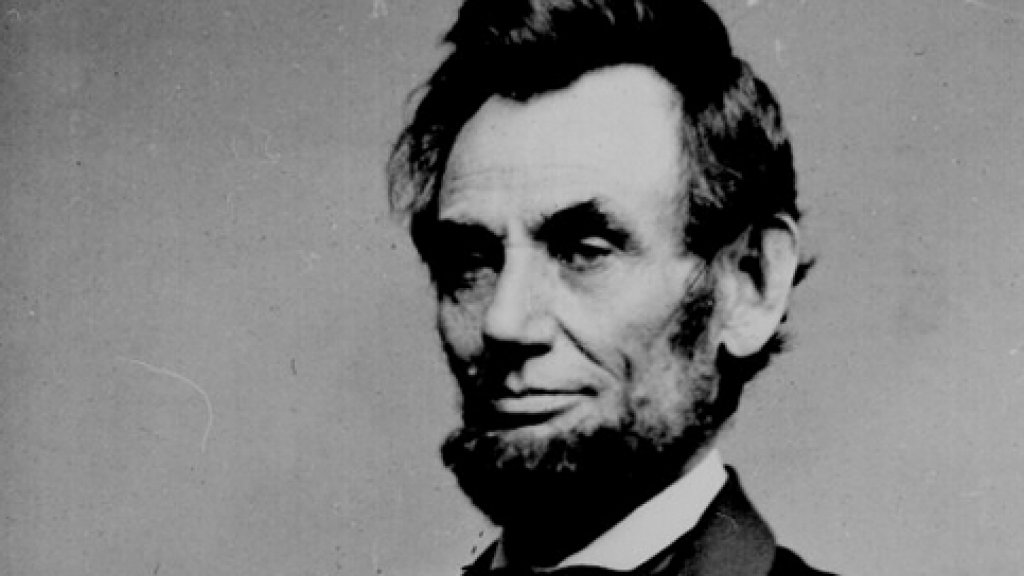

As Abraham Lincoln spoke to a war-weary nation on the occasion of his second inauguration, he engaged in what was arguably the most profound theological reflection of any presidential inaugural address. “Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God and each invokes His aid against the other,” he declared. “It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces but let us judge not that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered ~ that of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes. . . . With malice toward none with charity for all with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right let us strive on to finish the work we are in to bind up the nation’s wounds.”

We have not experienced a civil war this year, but we are still in the midst of an extremely polarizing, drawn-out national election that marks the culmination of the most divisive presidency of modern times. Evangelical Christians have been at the center of that division. On one side are the 75 percent of more of white evangelical Christians (along with millions of conservative Catholics) who are convinced that a vote for the Democratic ticket is a vote for abortion and the loss of religious liberty. On the other side are the 90 percent of Black Protestant Christians, joined by several million progressive white evangelicals and millions more mainline Protestants, Hispanic Catholics, and white progressive Catholics, who believe that a vote for Donald Trump is a vote for racism, xenophobia, environmental destruction, and misogyny. For four years, each side has read the same Bible and has invoked God’s aid against the other. Unfortunately, this will continue long after the balloting is over. Until this election is finally decided, we will continue to hear prayers for God to intervene on one side or the other of our national political conflict. And even after the election is finally resolved, the political polarization rending both the nation and the nation’s churches will continue.

So, perhaps while we wait for the last ballots to be counted, it would be appropriate at this moment to consider how we might bind up the political and emotional wounds of the American Christian churches that have been casualties of our nation’s cultural divisions this year. To do that, I’d like to consider how Christians on both sides of our political divide can think about this election as a redemptive moment, regardless of whether we’re pleased with the particular results.

Lost Elections Are Opportunities to Remake a Party

While no one enjoys watching their party lose an election, election defeats are wonderful opportunities for a party to reinvent itself in the next round. Christians who voted Republican this year because of abortion but nevertheless were concerned about President Trump’s character should rejoice at this prospect if President Trump loses this election. A defeat for Republicans (if it happens) will not destroy evangelical conservatism any more than the victory of Bill Clinton in 1992 or Barack Obama in 2008 did so. In each case, the Christian Right quickly reemerged as a stronger force, and Republicans swept the next midterm elections.

But I hope that this time, Christians who are Republican will not simply hope to win more votes in the next round. Instead, I hope that they will pray that their favored party will use its moment of reinvention to shed its platform positions that are antithetical to Christian values and rediscover a form of conservatism that is more consistently biblical.

One area where they could pray for this to happen would be immigration policy. In 2010, the Republican Party, in response to Tea Party pressure, made opposition to undocumented immigration a central campaign platform. This increased the party’s appeal to many rural whites and paved the way for Donald Trump’s candidacy, but it also eventually caused the party to lose the suburban vote.

From a Christian perspective, some aspects of this policy should be troubling. It set the party against any meaningful ticket to the future for young people who came to the United States without documentation in early childhood, and it put the party on a path toward approving the separation of children from parents at the border. For many Christians – even those who might be pro-life conservative Republicans – these stances are difficult to square with biblical values. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if the Republican Party’s reinvention of itself as a party that can once again become competitive in the suburbs prompted it to abandon these stances and once again embrace the more tolerant immigration policies that Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush, and John McCain once championed? A conservative Republican Christian should welcome the prospect that a 2020 election defeat could prepare the party for a return to issue positions that are more compassionate and, one might even say, consistently conservative.

And what about a Christian who is a progressive Democrat? If, against all predictions, Joe Biden and Kamala Harris lose, and the Democratic Party is in the political wilderness for several more years, how should a progressive Democratic Christian react? What sort of Democratic Party reorientation should Christians who are Democrats hope for?

If Biden loses this election, it will almost certainly be because Pennsylvania or another rust belt state did not vote for him. And the reason for this will likely be, at least in part, that he encountered more opposition from white Catholics than pollsters had expected.

For a pro-life Christian who is also a Democrat, this should raise hopes that the Democratic Party would become more concerned not only about the economic needs of the white working class, but also about their values – including the value that many Catholics place on the lives of the unborn. Perhaps it would be too much to hope that the Democratic Party would substantially change its position on abortion, but if it becomes clear that this played a larger role in voters’ thinking than any pollster had predicted, wouldn’t that be a welcome development?

Such exercises in hypothetical thinking indicate something that is too easily forgotten in the heat of an election:

No Party That Wins an Election Consistently Stands for Godly Principles

If this is the case, every election victory for our favored party needs to be tempered with the realization that long with the policies we might favor, the party will seek to advance some initiatives that are inconsistent with Christian values. This is not confined only to the most obvious issues of controversy, such as abortion. It’s also true of policies that don’t get as much press. Many Democratic Christians who support a consistent life ethic, for instance, have had to face the unfortunate reality that Democratic presidents have often proved to be nearly as likely as Republicans to engage in international military ventures that have at times killed not only foreign combatants but also civilians. Many Republican Christians who view the accrual of large amounts of government debt as a moral issue have had to confront the reality that their supposedly fiscally conservative party has often proved just as likely as Democrats to run up high deficits.

Both political parties will engage in behavior that many Christians decry. And if that’s the case, Christians cannot treat any election as a victory (or defeat) for the cause of righteousness. This does not mean that an election doesn’t matter or that the two parties are always morally equivalent. But it does mean that we need to avoid idolizing our particular political party. If we think that our chosen party is the only way to deliver victories for the cause of righteousness, we need to remember that:

Political Victories Cannot Deliver Culture-War Victories

In 1980, millions of evangelical Christians supported Ronald Reagan in the belief that he would rescue the nation from the effects of the sexual revolution, abortion, and moral decay. But Reagan could not deliver on this promise. The constitutional amendments that Reagan promised on abortion and school prayer were never adopted, and by some measures, the sexual revolution continued unabated. The year that Reagan took office, 18 percent of all children born in the United States were born to unmarried mothers, but by the time that Reagan left office, more than a quarter of the women giving birth were unmarried, with most of that increase occurring among white women, a demographic group likely to support Reagan and the Republican Party.

Conversely, the culture-war defeats that some politically conservative Christians fear will result from a Democratic presidential administration also never happen. During President Obama’s time in office, for instance, abortion rates decreased dramatically – from approximately 19 abortions per 1,000 women of childbearing age during his first year in office to only 13 abortions per 1,000 women during his final year in the White House.

Christians on the political left can also take comfort in the fact that some of the causes that are most important to progressive Christians, such as racial justice and legal redress for women who have experienced sexual assault, have received unprecedented attention during President Trump’s administration, in spite of (or maybe even because of) who was in the White House.

In other words, a defeat for a candidate does not at all mean defeat for a cause.

It is this realization, I think, that is the key to one of the most important blessings of our political system – the fact that up until now, no defeated occupant of the White House has refused to leave and to hand the responsibilities of the presidency to a successor from the opposing party. As long as we remember that the political issues we care about – let alone much more important things, such as the kingdom of God and God’s righteousness – are not tied to the fortunes of a particular candidate, we too, will find the grace to accept any election result.

And if, by some chance, our favored candidate has won, how should we respond? Perhaps with a hopeful optimism tempered by the realization that no political party can give us the just social order that we really long for. Elections are important, but they’re probably not as important as political candidates make them out to be. And if that’s the case, let’s not let the outcome of this election – whatever it ultimately may turn out to be – divide or alienate us from our fellow Christians. Let’s take a page from Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural address and spend the next few days or weeks seeking “charity for all” – especially those in our churches and colleges who might have voted for a different candidate, but who read the same Bible and pray to the same God.