The Gospel Coalition’s article earlier this month critiquing Randall Balmer’s claim to have discovered the “real origins of the Religious Right” has brought to the forefront once again the question of what prompted the Religious Right to emerge in the 1970s. But while this can be an interesting question, it doesn’t really provide much of an answer to the separate question that too many people conflate with it – the question, that is, of why the overwhelming majority of white evangelicals vote Republican.

This was the question I had when I began researching the history of the Religious Right twenty years ago. At that time, I accepted the myth that white evangelicals were not especially interested in politics before Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority mobilized them, and that many of those who had voted were Democrats. It was the Religious Right, I thought, that had made them Republican.

But I now have a very different view of the history. I now realize that white evangelicals started voting Republican long before Falwell and his Moral Majority arrived on the scene to mobilize conservative Christian voters for Ronald Reagan.

Here’s a quick trivia question to demonstrate that fact: Which Republican presidential candidate holds the record for receiving the highest percentage of the evangelical Protestant vote (at least as measured by National Election Survey data)? Was it Donald Trump? Ronald Reagan? George W. Bush?

Actually, it was Richard Nixon in 1972. According to NES data tabulated by political scientist Lyman Kellstedt and his cohorts, Nixon received 84 percent of the evangelical Protestant vote in 1972. Reagan received 74 percent in 1984, Bush received 78 percent in 2004, and Trump received 81 percent in 2016.

So, it appears that Falwell and the Moral Majority were never needed at all to get white evangelicals to start voting Republican. Nixon had already done that. And before that, according to the NES data, a majority of evangelical Protestants in the nation had supported Eisenhower. Whatever Falwell did – and whatever causes mobilized him – his actions were not the main reason why evangelicals started voting Republican.

How then should we tell the story of evangelical Republican partisanship? When did it begin, and what were its sources? As surprising as it may seem, the answer – at least for northern evangelical institutions such as the National Association of Evangelicals and Christianity Today magazine – may begin with developments that occurred as early as the 1850s, when the Republican Party formed as the party of Protestant moralism. That’s because for a place like Wheaton College, there never was a time when it wasn’t a bastion of Republican support; Republican voting could be traced back to the college’s founding in the mid-nineteenth century, when the Republican Party was the party of Protestant moral campaigns.

The Deep Republican Roots of Northern Evangelicalism

The Republican Party attracted a lot of northern evangelical support when it initially formed, because many evangelicals whose moral fervor had been aroused in the Second Great Awakening were attracted to the party’s opposition to the expansion of slavery. This was true of the evangelicals who started Oberlin College, for instance, as well as some of those at northern Baptist colleges such as Brown. Of course, it was not true of southern evangelicals, nor was it true of some northern working-class evangelicals who remained Democrats. But nevertheless, while both the Democratic and Republican parties had significant evangelical constituencies in the mid-nineteenth century, it was the Republican Party that established itself as the party of Protestant morality. In addition to taking a stand against slavery, the Republican Party also made a campaign against Mormon polygamy a key part of its nineteenth-century mission. The Republican Party was also more supportive of legislation against alcohol and other alleged moral vices than the states-rights, moderately libertarian Democratic Party was at the time.

In northern cities, the Democratic Party became the party of Irish Catholics and other non-Protestant immigrants and, to a certain degree, the working class. Across the nation, it was associated with the principle of white supremacy, but also hatred of the wealthy Protestant eastern establishment.

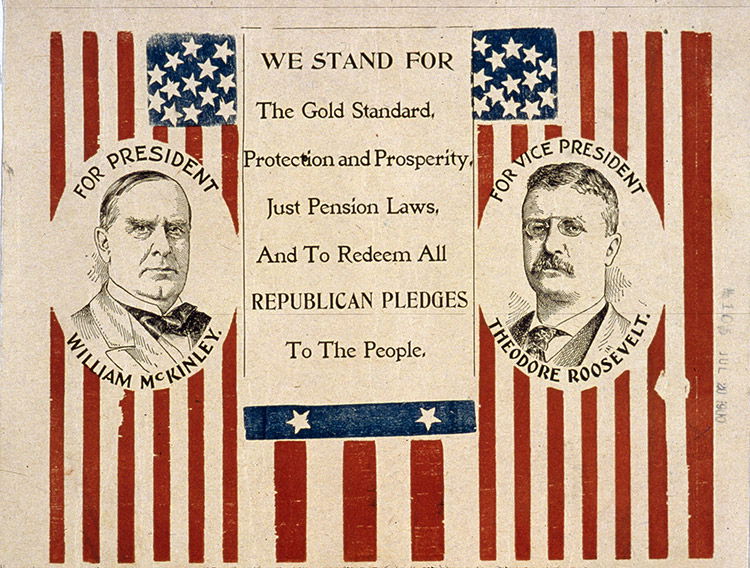

The Republican Party, by contrast, was the party of the sober, industrious, Protestant middle class – the sort of northern Methodist families that people like President William McKinley came from, for instance. In their view, the Democratic Party was the party of “rum, Romanism, and rebellion,” as one New York minister phrased it in 1884.

In that environment, large numbers of northern evangelicals voted Republican. In the early 20th century, a lot of these northern evangelicals – including those at Oberlin, for example – sided with the modernists in the fundamentalist-modernist controversy and became liberal Protestants. But when they did so, they remained Republican (at least until the 1930s, if not longer), because the Republican Party was the party of northern Protestant morality. Those that sided with the fundamentalists – as Wheaton College did, for instance – also remained Republican, although they became increasingly more suspicious of the Social Gospel and more enamored with the individualism of the conservative wing of the GOP.

In the 1930s, large numbers of liberal Protestants who saw the correlation between Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal and the Social Gospel for which they had long been working became supporters of the newly remade Democratic Party, but the northern fundamentalists or evangelicals remained loyal Republicans who staunchly opposed the “wet” President Roosevelt and his urban Catholic constituency. The New Deal represented a centralization of federal authority that might even be a harbinger of the anti-Christ, northern dispensationalist magazines such as Moody Monthly argued.

Thus, when the National Association of Evangelicals and its corresponding “new evangelical” movement formed in the 1940s, all of its leaders – including Harold Ockenga, Carl Henry, and a host of others – were fiscally conservative Republicans who viewed the urban Catholic political machines that dominated northern cities as a corrupt threat to the republic. All of the major northern evangelical institutions, such as Wheaton College, Fuller Theological Seminary, and (after it formed in 1956) Christianity Today, also leaned strongly toward the Republican Party. Registered Republicans outnumbered registered Democrats among CT subscribers by approximately four to one in 1960 – and the percentage of those who voted Republican in presidential elections was even higher. A 1956 Christianity Today survey of Protestant ministers in its network found that 85 percent planned to vote for President Dwight Eisenhower, while only 11 percent planned to vote for his opponent, Adlai Stevenson.

Southern Protestants who moved north (even for a short time) to rub shoulders with northern evangelicals in the mid-20th century often became lifetime converts to their brand of conservative Republican politics. This was true of southern fundamentalists such as John R. Rice and Bob Jones Jr. It was also true of more moderate evangelicals such as Billy Graham, who became a strong supporter of the Christian civil religion of President Eisenhower and his vice president, Richard Nixon.

Historians whose research focuses on the politics of northern evangelicals have found strong support for the Republican Party in every era they have examined. Matthew Avery Sutton found this phenomenon among northern fundamentalists in the 1930s, Kevin Kruse found it among supporters of Eisenhower’s civil religion in the 1950s, and I observed it among Nixon’s evangelical supporters in the 1970s.

While immersed in our own research, it’s easy to imagine that the era that we’re studying ourselves was the critical moment when modern partisan alliances were forged. To be sure, each of the decades I mentioned marked a turning point in the process of an evangelical alliance with the Republican Party. Yet none of those points marked the beginning of this alliance. In the decade or two before the 1930s, Billy Sunday was just as much of a Republican partisan as the fundamentalists who excoriated FDR, and in the decades before that, there were plenty of northern evangelicals who identified the GOP with true Christian morality and the Democratic Party with Catholic liquor interests.

The Conversion of Southern Evangelicals to the Republican Party

But of course, I’ve carefully focused this discussion so far on northern evangelicals. What about southern evangelicals? When did evangelicals throughout the nation – in both North and South – form a unified Republican voting bloc? And was Falwell’s Moral Majority necessary for that coalition to form? After all, didn’t southern evangelicals vote overwhelmingly for Jimmy Carter in 1976 – a sign that they didn’t really become Republicans until the end of the 1970s?

It is true that southern evangelicals were not Republican for much of the 20th century. While northern evangelicals of the late 19th and early 20th century viewed the Democrats as the party of Catholic urban political machines and liquor interests, southern Protestants thought of it as the party of William Jennings Bryan, who became a hero to an entire generation of southern conservative Protestants who shared the Great Commoner’s opposition to alcohol, evolution, and the eastern banking establishment. Bryan was from the Great Plains – an agrarian region that in the late 19th century tended to be culturally and politically much closer to the rural South than to northern cities – and his politics appealed to white southern conservative Protestants. In the 1930s, these same Protestants generally supported Franklin Roosevelt, even while northern evangelicals did not.

But southern Protestant ministers were never as solidly Democratic as other voters in their region. When the Democratic Party nominated the “wet” Catholic Al Smith for president in 1928, numerous Southern Baptist and Southern Methodist ministers repudiated him and voted Republican. Some of them did the same in 1960 when another Catholic, John F. Kennedy, headed the Democratic ticket. And even when Catholics were not on the ballot, southern white evangelicals were highly receptive to the Republican Party’s promise of civil religion and the politics of a generically Christian morality – which is why they liked Eisenhower in the 1950s and were even more enthusiastic about Nixon in the 1970s.

By the early 1970s, Billy Graham, Richard Nixon, Christianity Today, the National Association of Evangelicals, and some of the leaders of the Southern Baptist Convention had succeeded in forging a transregional, moderately conservative, evangelical political culture that opposed secularization and advocated returning a Protestant-style moral regulation to American politics to confront the sexual revolution and the cultural changes of the preceding decade. In their quest for a new Eisenhower, white evangelicals settled on the general’s former vice president, Richard Nixon. While a small minority of evangelicals who opposed the Vietnam War formed Evangelicals for McGovern, the overwhelming majority of evangelicals in both the North and the South threw their support to Nixon in 1972, believing that he was the only candidate who could protect a beleaguered Christian America.

Watergate shocked many Christians who had placed their faith in Nixon, and it prompted many evangelical leaders to swear off partisan loyalties for a while and resolve to scrutinize the personal morality of presidential candidates more closely. For some, that meant voting for Jimmy Carter in 1976 – though support for Carter was considerably less unanimous among evangelicals than later mythologies might have suggested. Public opinion polls in 1976 showed that evangelicals split their vote almost evenly that year, with 51 percent voting for Ford. While Carter was popular in much of the South, northern evangelicals were much more likely to vote for the Republican incumbent, who had a son attending Gordon-Conwell and who was very popular among the Reformed Christians in Grand Rapids, Michigan, who had been his congressional constituents for decades. Graham, too, probably voted for Ford – although, chastened by Watergate, he kept much quieter about that choice than he had about his support for Nixon in 1972.

So, what happened in the late 1970s? Did the emergence of the Christian Right during the Carter years have any significance in turning evangelicals into Republican partisans?

The Christian Right resurrected the cultural concerns that had prompted an overwhelming majority of white evangelical voters to support Nixon in 1972, but this time New Right political strategists helped convince evangelicals to pay more attention to platforms rather than candidates and to turn a few key issues (abortion, gay rights, and school prayer) into political litmus tests. In 1972, evangelicals had supported Nixon because they were attracted to his moral rhetoric about the decline of key values in American life, but they didn’t quiz him about his stance on abortion or ask for the details about his policies on marijuana. By 1980, many evangelicals were convinced that the issues a candidate stood for were more important than the character traits a candidate had – or at least that was the argument of the New Christian Right.

But what would have happened had Jerry Falwell never met Paul Weyrich? Would evangelicals have split their vote in 1980, with a sizeable number siding with the Democrats, as they had in 1976? Probably not. Evangelical support for Reagan extended far beyond the rather small number of evangelicals who were associated with the Moral Majority or related organizations. After all, evangelical roots in the Republican Party ran deep. For northern evangelicals, they extended back far longer than any of them could remember, and for many southern evangelicals, those roots extended back to the Eisenhower administration. 1976 was an anomaly, and even in that year, the percentage of the evangelical vote that went for Ford slightly outpaced the share of the national vote that he received. It seems difficult to imagine that in a year in which Reagan won a landslide electoral victory, he wouldn’t have won a solid majority of the white evangelical vote, with or without the Moral Majority’s efforts.

With the single exception of 1964 – when the nation as a whole had returned Lyndon Johnson to the White House in one of the greatest landslides in American political history – a majority of evangelicals had supported the Republican presidential candidate in every election since 1952. And, of course, that trend has continued unabated since 1980; an overwhelming majority of evangelical voters invariably support the Republican candidate in every presidential election.

Such deeply rooted partisanship looks odd only because other Protestants in the United States have moved in the opposite direction. For more than half a century, mainline Protestants have been moving away from the GOP, and Black Protestants abandoned the Republican Party in the 1930s.

But evangelicals have increased their commitment to the Republican Party even as both the party and the evangelical movement have shifted to the South. In the mid-20th century, Republican voting among evangelicals was most pronounced among those in the North, but over the past few decades, the southernization of American evangelicalism has produced a form of GOP Christian politics than northern evangelical Republicans of the Eisenhower years, such as Carl Henry, would probably never have recognized. The Republican Party to which evangelicals are committed today is not the same party as Billy Graham admired. But the roots of evangelicals’ current commitment to the party extend back to Graham and Henry’s activities – and even to events long before their time.

That’s why it didn’t take Falwell or the New Christian Right’s alliance with Ronald Reagan to get evangelicals to start voting Republican. Most of them had been pulling the GOP lever long before the Moral Majority formed – which means that if we want to understand why evangelicals vote Republican, we shouldn’t focus just on Falwell; we need to look at a century or more of evangelical political culture.

This doesn’t mean, of course, that evangelical patterns of Republican voting cannot be reversed. Already there is some evidence that the trend has been reversed at a few northern evangelical institutions that long voted Republican – even if, by contrast, southern white evangelicals are becoming ever more entrenched in Republican politics. But it does mean that evangelical Republican voting habits are very deeply rooted, and that they are not the product of a single serendipitous event, such as a secret backroom deal or the machinations of one particular short-lived political organization. The Republican Party has changed a lot in 150+ years, but its commitment to a particular strand of individualistic Protestant moralism has continued to survive in some form – and with it, its continued appeal to large numbers of white evangelical Protestants. Once we understand that, the white evangelical attraction to the GOP will look less like an anomaly – regardless of whether we agree with it.