For the May 1st-15th Patheos Book Club

In early 1979, Hoa Chung had a dream. Although plans were coming together to leave communist-ruled Vietnam for a better life elsewhere, this dream was not a daydream of hope, but a vivid sleeping-dream. In it, her husband Hoa and their  eight children fell dead in the middle of a thriving Vietnamese market. Then, they were resurrected one-by-one through the ministrations of “a man dressed in a white robe, with long brown hair and a beard to match (89).” Although she sought counsel, she could not identify the man in her dream until she walked through the doors of Grand Avenue Baptist Church (where the Vietnamese Church met) in Fort Smith, Arkansas later that year and saw his “portrait” on the wall.

eight children fell dead in the middle of a thriving Vietnamese market. Then, they were resurrected one-by-one through the ministrations of “a man dressed in a white robe, with long brown hair and a beard to match (89).” Although she sought counsel, she could not identify the man in her dream until she walked through the doors of Grand Avenue Baptist Church (where the Vietnamese Church met) in Fort Smith, Arkansas later that year and saw his “portrait” on the wall.

Where The Wind Leads: A Memoir by Vinh Chung tells of two parallel journeys. The first describes the arduous journey of the Chung family as they traveled as refugees from Vietnam, eventually finding refuge–and success–in America. The second describes the journey of Vinh’s family from tam giáo–the “triple religion” of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism (33)–to Christianity.

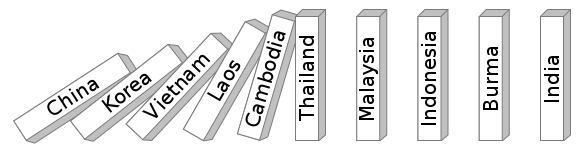

The descendants of 19th-century Chinese emigrants to southern Vietnam, theirs is a riches-to rags-to riches story. Through hard work, the Chung Family built a thriving rice-processing business by the middle of the 20th century, enriching their family. Following the U.S. military withdrawal from the subcontinent, by 1975 communist forces united the North and South Vietnam as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. By 1979, the Chungs fell under dual suspicion from the communist government. As former bourgeoisie, communist ideology cast them as villains while their Chinese ethnicity doubled their danger in wake of the acrimonious split between Ho and Mao.

Leaving Vietnam in 1979, the Chungs became boat people. Like so many others, they desperately sought refuge in neighboring Asian countries (Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand) who had exceeded both their emotional and physical capacity to receive any more refugees. The Chungs and those who shared their boat were attacked by Thai Pirates, assaulted by Malaysian soldiers, towed out to sea in a damaged boat and set adrift by the same soldiers, and then attacked once more by pirates. Finally, they were rescued by the Seasweep, a World Vision ship purchased for that purpose.

Eventually, the family settled in the United States where Thanh Chung, Vinh’s father, worked long hours in blue collar jobs to support the family. Later the Chungs would open a restaurant where all eleven children worked to support the family. This example and environment imbued a strong work ethic in Vinh and his siblings. Combined with an emphasis on education, it catalyzed their success. Collectively, they hold “twenty-one university degrees, including five master’s and five doctorates from institutions such as Harvard, Yale, Georgetown, Stanford, George Mason, Michigan, and Arkansas (4).” No one can deny that this was quite an achievement for refugee children who spent their early childhood years in Section 8 housing.

The Chung family’s journey is a classic Horatio Alger-type success story. Out of abject poverty and substantial prejudice, an immigrant family found success in America through honesty, hard-work, and determination. Vinh, who takes center stage in the second half of the book, earned his M.D. from Harvard and now practices medicine as a skin cancer surgeon. Throughout the book, he paints America as the land of opportunity, but also hints that forces more substantial are were at work.

A subtle providential interpretation of events permeates Where the Wind Leads. The title itself pays homage to that understanding. The winds of the South China Sea, after all, blew their ship into the path of the Seasweep when so many other boats languished and were not rescued. In addition, as the pages turn, the Chung family is gently guided towards faith in Jesus Christ by the events recounted in the book. After their rescue, for example, Thanh Chung embraced Christ as Stan Mooneyham, then president of World Vision, preached the gospel to the refugees on board the Seasweep. Commitments were solidified when the family became a part of the Vietnamese church in Fort Smith. The man in Hoa’s dream had brought life to each of her family members.

In the last chapter of the book, “Giving Back,” Vinh’s own commitment takes center stage. Whereas many who have succeeded in a similar fashion develop a self-congratulatory air, Vinh’s Christian faith allows him to clearly perceive the magnitude of the opportunity afforded him as well as his Christian responsibility in light of it. He writes, “I worked long and hard to get where I am today, but the humbling truth is that all my hard work has been possible only because of a blessing I received that I did nothing to deserve. I believe that blessing is something I am expected to pass on to other people in any way I can (342).” His words stand as a gentle rebuke for those of us who often forget just how blessed we are to have any opportunities.

An engaging, well-told story, in the end analysis Where the Wind Leads also highlights some important themes: the importance of providing opportunity for impoverished families–Head Start and public housing both played a role in the Chung family’s success; the empowering role of families in children’s success; and the characteristically American nature of welcoming immigrants. These, along with other American motifs, are valuable legacies we ought to recall in our contemporary debates about policy. I might even suggest they ought to shape them.

Further, Where the Wind Leads also reminds us that policy decisions impact real people and historical currents change people’s lives. As French colonial rule came to an end in Indochina and the Domino Theory dictated that the United States involve itself in Vietnam, people like the Chungs were caught in the backwash of the end of colonialism and the war-by-proxy that the Cold War had become. Despite normative evaluations of the policy decisions involved, Christians ought to be concerned with this human impact of such decisions. Thankfully, in 1979 Christians like Stan Mooneyham and the leadership at World Vision were. Hopefully, in 2014 we will also be.