“Don’t believe those indios, Vero,” the Mexican scholar told me in Spanish as we walked away from the Franciscan friary. “They don’t know their history; they’re inventing rituals. Talk to the scholars here instead.”

I didn’t know how to respond and nearly tripped over the colonial cobblestones in surprise. I knew that prejudice against native people persisted in modern Mexico, but didn’t expect to hear a renowned Mexican historian who specializes in native peoples express the same sentiment. Perhaps I was naïve.

It was October 2019 and I had traveled to Mexico to participate in a series of events commemorating the 500-year anniversary of the Cholula massacre. Long-time friend, mentor, and renowned colonial Mexican historian, fray Francisco Morales Valerio, O.F.M., Ph.D, had invited me to speak at a 2-day symposium, “Mirada retrospectiva sobre Tollan Cholollan Tlachihualtépetl a cinco siglos de la masacre” (Retrospective Look at Tollan Cholollan Tlachihualtepetl Five Centuries After the Massacre), held October 18 and 19, 2019 in the Biblioteca Franciscana (Franciscan Library), associated with the University of the Americas-Puebla, in Cholula, Puebla, Mexico. Cholula has long been my research site and it was my honor to be the only scholar invited from outside Mexico to participate.

Despite the red and white banners affixed to streetlights throughout Cholula, and the posters fastened to chain link fences that gravely acknowledged the commemoration, my taxi driver the night I arrived was unaware of the massacre. More poignant was a display in the town square near the site of the massacre: an oversized “500” illuminated in red affixed to a capitalized “CHOLULA,” illuminated in white, which drew passersby for selfies. Red and White. Blood and Innocence.

View of plaza with the church atop the Tlachihualtepetl (Man-Made Mountain) in the distance

Such appeared to be the unifying theme of Cholula’s commemorations of the quincentennial of the massacre: innocent inhabitants overwhelmed by the brutality of Castilian invaders, who paused here in October 1519, en route to vanquish Tenochtitlan, modern-day Mexico City, sixty miles to the west. The traditional narrative oversimplifies the event, effacing the presence of indigenous aggressors – Cortés’ thousands of indigenous allies – and overlooks the deeply-rooted regional divisions predating Iberian arrival. Historians like Matthew Restall, in When Montezuma Met Cortés: The True Story of the Meeting that Changed History, place the Cholula Massacre within the larger narrative of the Spanish Invasion and March to Tenochtitlan. Analyzed this way, complexities emerge, prompting Restall to argue that Cortés’ allies from Tlaxcallan, who hated the Cholulteca and outnumbered the Europeans, essentially forced an exhausted Cortés and his men to pass through Cholollan, as it was known, to slaughter their enemies before taking him to Tenochtitlan. Not all scholars accept this argument. In contrast, the traditional narrative, largely drawn from European sources, appears to diminish native agency in the past, and to efface native peoples as actors in the present even as they commemorate the past.

Disagreement over how to interpret the past and understand the present reflected but one example of the dissonance that manifested in contemporary Cholula during the quincentennial activities. Due to the limitations of this blog post, I will address only a few.

The official commemoration events began on Tuesday morning, October 15, 2019 with a Nahuatl-language Ceremonia luctuosa (mourning ceremony) in the patio of the church of San Gabriel, part of Cholula’s sixteenth-century Franciscan evangelization complex. This patio, which once served the sumptuous teocalli (god-house) dedicated to Quetzalcoatl, the Plumed Serpent, was the site of the massacre. When Franciscans settled in Cholula in the winter of 1528/1529, they would hold Mass outdoors next to the temple’s rubble to accommodate the large numbers of native Cholulteca, a common practice in colonial Mexico. It would be twenty years before they organized native laborers to build the church. Contrary to what one might think, native Cholulteca enthusiastically constructed it, not necessarily because they accepted the Christian God, but because as historian James Lockhart has demonstrated, like all Mesoamerican peoples they viewed the monumental structure as an analogue of the pre-contact temple, symbolizing Cholula’s sovereignty and corporate identity.

Michael Bricaire Torres (San Pedro Cholula’s Secretary of Culture) is in black, 5th from the left; Luis Alberto Arriaga (President of San Pedro Cholula) is 7th from the left; next to him is fray Francisco Morales Valerio, OFM, PhD in brown; also present was Karina Pérez Popoca (President of the neighboring municipality of San Andrés Cholula)

A line of officials welcomed us to the mourning ritual, proposing reconciliation and harmony, recollecting death and devastation, and recognizing resistance and resilience. The microphone lingered with Capitana Guadalupe Tonatiuh, a Cholulteca dancer whose very name reflects the blended past and present that comprises contemporary Cholula. She approached this day not in sorrow, she told us, but as a reminder to be good people who respect everyone.

A conch shell’s lonely lament erupted and resonated, its cry catalyzing the cluster of indigenous dancers nearby. Our attention diverted toward the atrial cross, the hum of Spanish, the conqueror’s language, ceded to Nahuatl, Cholula’s ancestral language. The ensuing chant honored Quetzalcoatl, the Plumed Serpent, whose regional worship once centered here, beneath our feet, in a hallowed ceremonial precinct in Cholollan. Plumage, incandescent in the sun, yielded to the ritual rhythms of the dance; the rattle of ayoyotes (shell anklets/wristlets) accompanied the incensing of ritual bundles at the foot of the cross. The dancers moved and the soil in the church patio shuddered, reminiscent of the trembling of the earth in this sacred place in October 1519, when a Castilian harquebus initiated a massacre of thousands of native Cholulteca in a matter of hours.

According to San Pedro Cholula’s Secretary of Culture, Michael Bricaire Torres, the mourning ritual marked the first time in 500 years that native Cholulteca had been allowed to perform purely indigenous – rather than indigenous-Christian – ritual in the church atrium. According to Huitzil, the Cholulteca who in the year 2000 founded the group that danced during the ceremonia luctuosa, this marked the second such occasion. Huitzil (which means hummingbird) would seem to be correct, for newspaper articles from 2018 include photos of San Pedro Cholula’s president receiving incense from indigenous dancers in the patio of the Franciscan friary during a commemoration of the 499th anniversary of the massacre.

After the ceremony concluded and officials had lined up with native dancers for photos, reporters surrounded the municipal president, Luis Alberto Arriaga, a medical doctor and former television journalist, who announced that from this day forward, native Cholulteca would be welcome to commemorate the massacre in the church patio every October 15. Considering this a positive, I turned to speak with the native dancers and learned that they had a different perspective. The municipal government and local academics did not include them in planning commemorative events, they said, and dismissed them when they disagreed about the placement of a commemorative monument. Most of the time, they told me, the scholars and native dancers operated independently. When I invited the indigenous dancers to the symposium, they politely declined.

With my late friend Matilde and Tula, a Cholulteca dancer

Like many commemorations, Cholula’s quincentennial defies simple classification, revealing more about the present than the past. How does one commemorate a massacre that serves as one episode in the larger narrative of Iberian Invasion in a country where violence against native peoples prevails? How does one commemorate an attack on a culture the world generally perceives, however incorrectly, as violent? How does one commemorate a violent event that resulted in Mexico’s current identity as a land of mestizaje, in a country that is predominately culturally, if not actually, Catholic?

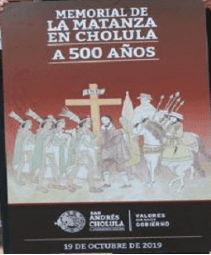

Poster announcing a Memorial of the massacre with native people and Castilians uniting around a cross

More than a singular commemoration, Cholula offered a repertoire of parallel commemorations, holding distinct meanings for its various actors, with each faction preparing its own events and no grand design aside from the opening and closing event in the church patio, the site of the massacre. Mimicking the conflicting accounts of the 1519 massacre found in Castilian and indigenous chronicles produced in the colonial period, the quincentennial commemorations evidenced contested official and unofficial narratives, with an underlying privileging of the traditional account. Even the expression used to speak of the past proved contentious: whereas scholars typically apply “pre-contact,” “pre-Hispanic,” or “pre-Columbian,” to the indigenous period, native Cholulteca protested the Eurocentric nature of these expressions, proposing the term tiempos pre-cuauhtémicos (pre-Cuauhtémoc times), that is, the time before the death of the last independent Mexica ruler, Cuauhtemoc, whom Iberian conquistador Hernando Cortés hung in modern-day Honduras in 1525 after taking him on expedition.

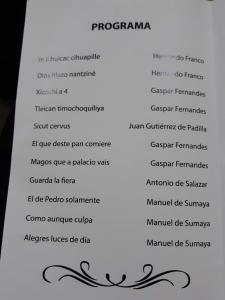

Several events during the commemorations underscored the disconnect between native Cholulteca and the people who studied them; I will mention two. On the first night of our symposium, we had a beautiful choral concert in the church of ancient sacred music in Nahuatl, using indigenous instruments performed by native Cholulteca. The performers were professionally trained and sang in multiple languages to an enthusiastic crowd.

Program for our “Concierto coral de música sacra antigua en Nahuatl”

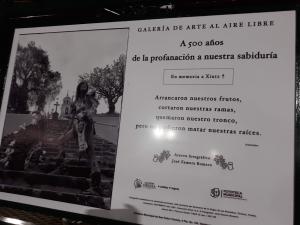

As we filed out of the church afterwards, we heard the chants of native Cholulteca in the plaza across the street; I was the only academic who crossed over to witness the indigenous commemoration. The dancers, who had gathered while we were in concert, had laid bundles on a sidewalk near the not-yet-revealed commemorative monument. They moved amidst a “Gallery of art in the open air” whose photographs explored “500 years since the desecration of our wisdom.” The translation on the introductory plaque reads:

They plucked our fruits,

cut our branches,

burned our trunk,

but they could not kill our roots.

No native dancers attended the concert, and no local concert-goers (I am a foreigner) attended the ritual dance.

Cholulteca ritual near the unrevealed monument to the massacre

“Gallery of art in the open air” exploring “500 years since the desecration of our wisdom”

As a second example, at the end of the second day of our symposium, speakers, participants, and officials gathered across the street near the place where the dancers had incensed their bundles the night before. Notably, no native dancers were present as the municipal president unveiled the monument commemorating the massacre. Instead, noted colonial Mexican scholar Francisco González-Hermosillo Adams, from the National Institute for Anthropology and History (INAH) in Mexico City, read the Nahuatl inscription. His words – in Spanish – are etched into a stone nearby. The monument itself consists of an image from the Lienzo de Tlaxcala, a sixteenth-century indigenous text produced by Cortés’ largest contingent of allies to demonstrate their value during the three-year war to take Tenochtitlan.

The new monument in the town square’s park commemorating the 1519 Cholula Massacre

The church of San Gabriel and the monument by night

Cholula has many active participants in various capacities dedicated to preserving its past. Scholars. Friars. Students. Officials. Local native people. Each commemorated the massacre in their own way, reflecting Cholula’s fragmented contemporary reality. Just as the history of the Iberian invasion remains contested, so too does the massacre. Even with 500 years of space and time to consult one another, to reflect together, to work together, Cholula’s quincentennial reveals Mexico’s contemporary reality, which laments the treatment of colonial native peoples and extols the accomplishments of native peoples in the past while retaining pejorative attitudes towards native people in their midst.

Cholula is a beautiful place, but like many places living with a colonial legacy, it has yet to escape its past.