Over the past couple of decades, one of the most active and creative fields of historical scholarship has been the history of the senses, of the ways in which people interact with their worlds. To borrow the words of a recent blurb, what did the past sound like, taste like, smell like?

You can actually make reasonable efforts at knowing such things. One excellent book I read last year was Moravian Soundscapes by Sarah Justina Eyerly, which uses a “sonic history” to understand the Moravian missions in early Pennsylvania. In another religious context, the role of the senses in worship and devotion has repeatedly driven fundamental conflicts within the Christian world, from Iconoclasm to the Reformation and beyond. To get a sense of just how lively a field this is, check out the highly selective working bibliography I have posted online. Obviously too, studying the senses raises the issue of people whose senses are impaired in different ways, and disability is another very sizable topic in contemporary historical research and publication.

Here, I will be using a different approach, by focusing on one gospel in particular, namely that of John, which is famously sensory in its approach: just look at how extensively it treats seeing, vision, and blindness. But rarely – I almost want to say uniquely – John deploys smells as an essential part of his narrative, and comes close to telling his story by means of those smells. I can’t think of many authors who have done such a thing, or so effectively. (With Proust, it was a taste).

The History of Smell

It is impossible to understand ancient societies without recognizing the very different worlds of smell in which they operated. Sanitation was often dreadful, and society relied totally on animals for every aspect of life. Kings and nobles distinguished themselves by their access to very pricy oils, which were intended to produce wonderful smells. Look for instance at Psalm 45, which was probably designed for a royal coronation:

Thou lovest righteousness, and hatest wickedness: therefore God, thy God, hath anointed thee with the oil of gladness above thy fellows.

All thy garments smell of myrrh, and aloes, and cassia, out of the ivory palaces, whereby they have made thee glad.

Smell was (and remains) intimately associated with class and power: of course, the hard-working poor and enslaved smelled bad. In modern times, the language of xenophobia and racism is saturated in images of dirt, smell, and hygiene.

Smell also had a vital religious context. Imagine a temple, which was constantly sacrificing animals, and which must have resembled an abattoir. Of course you needed huge quantities of incense to counteract that. Also, anyone who could afford it used fragrant products, including for burials. There is now a fine collection of essays on these matters in Kiersten Neumann and Allison Thomason, eds., The Routledge Handbook of the Senses in the Ancient Near East (Routledge Taylor & Francis, 2022): just look at the impressive range of topics covered.

The best evidence of the religious power of smell was the word that we give to the most exalted figure in the Judeo-Christian system, the one who was anointed with wonderfully smelling oil imported from distant lands: he was the Anointed, the moschiach, the messiah, the Christos. Of its nature, anointing implied sweet-smelling. We might even say that literally, “Christians” are “Those Who Follow The Sweet-Smelling One.” When such a king was born, you gave him gold for display, fragrant frankincense for perfumes and incense, and aromatic myrrh for anointing, especially for burial.

Smells could be sacred.

Smell in John’s Gospel

All of which brings me to the Gospel of John. Whatever its undoubted spiritual power, that gospel is one of the most intriguing and sophisticated literary texts you are likely to encounter in any religious tradition. Although the text as we have it is the product of multiple layers of composition and editing, you can see so many literary devices and strategies that simply inspire awe, so many examples where a theme is introduced in one portion and amplified by being echoed elsewhere. I have elsewhere written about the use of one such doublet, the twin coal fires that symbolize Peter’s betrayal, and his forgiveness and reconciliation. Here, I will describe another olfactory doublet, a phrase I just invented for moments when one smell recalls and reverses another smell. And I’ll suggest what it might tell us about the gospel’s meaning.

Scholars have often remarked how John used a full five sense approach to telling his story, and (as in the case of the coal fires) that included the sense of smell. But let us look at what is presently one of the gospel’s more contorted sequences, where we can clearly see major editorial rearrangement. The passage occurs in what is now chapters 11-12, although of course the original readers knew nothing of any such divisions. It tells the story of a group of siblings who lived at Bethany, namely Mary, Martha, and Lazarus.

The Family at Bethany

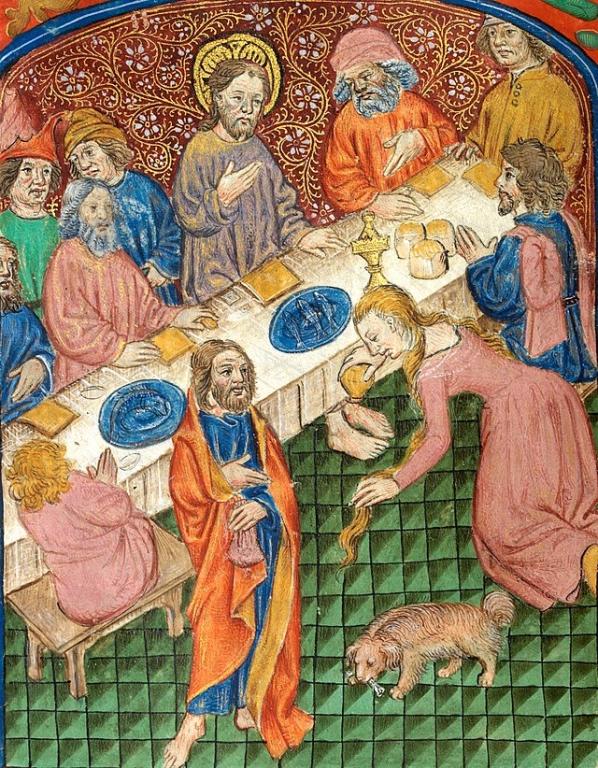

As we have it – and I repeat the phrase – the sisters know that Lazarus is ill, and they send to ask Jesus to help. He does come at their request, but arrives when Lazarus has been dead four days. However, he heals him, raising him from the dead. The miracle stirs the Jews to anger, provoking them to try and kill him. Jesus eventually returns to the siblings’ house, several days before the Passover at which he is himself to perish. In a legendary gesture, “Mary took a pound [litran, λίτραν] of costly ointment of pure nard and anointed the feet of Jesus and wiped his feet with her hair; and the house was filled with the fragrance of the ointment” (John 12.3). In the context of the gospel, this is clearly an anointing for his approaching death and burial, and the quantity is incredible. The NIV translates λίτραν as pint, and it is in fact the same word that we know today as “liter,” although the actual size would be less than half a modern liter. Even so, if this is meant to record a historical event, the cost would be staggering. Judas Iscariot is shocked by the waste of money involved in the spectacular event, and protests, only to be silenced by Jesus.

That story is well known, but it is oddly presented in John’s gospel. When we first meet the family, it is with an explanatory reference to an event that has not yet occurred: “Now a certain man was ill, Lazarus of Bethany, the village of Mary and her sister Martha. It was Mary who anointed the Lord with ointment and wiped his feet with her hair, whose brother Lazarus was ill” (11.2). But although the text suggests that we should have met this Mary and Martha before, they are new characters to us, and the foot-washing scene is in the following chapter. As narrative strategy, that is truly odd. Some translations, including the NIV, put the explanatory line about Mary in parentheses, indicating how extraneous it seems to the text.

The Synoptics

Tracing the origins of John’s story shows yet again how that particular tradition developed and built upon stories that were already decades old, and which had been elaborated by earlier writers. The tale recalls an incident recounted in the Synoptics, initially that of the “anointing of Jesus” in Mark 14. In that passage,

“While he was in Bethany, reclining at the table in the home of Simon the Leper, a woman came with an alabaster jar of very expensive perfume [muron], made of pure nard. She broke the jar and poured the perfume on his head.”

It is not Judas but the bystanders who are shocked at the spectacular waste of money, and Jesus rebukes them similarly. Nor is there a reference to washing his feet with her hair. Matthew reproduces this story closely, but Luke (7.36-50) interprets it quite differently:

“When one of the Pharisees invited Jesus to have dinner with him, he went to the Pharisee’s house and reclined at the table. A woman in that town who lived a sinful life learned that Jesus was eating at the Pharisee’s house, so she came there with an alabaster jar of perfume. As she stood behind him at his feet weeping, she began to wet his feet with her tears. Then she wiped them with her hair, kissed them and poured perfume on them.”

Luke also, separately, tells a story of Jesus visiting a pair of sisters called Mary and Martha, but this is quite unconnected with the anointing.

How John Adapted the Story

John’s version, then, comes at the end of an older tradition, in which the story of the woman who simply performs an anointing at Bethany has escalated to tell how she cleans his feet with her hair. By this point too, the story has merged with that of the two sisters, and it is about to incorporate the (originally independent and free-floating?) Lazarus story.

John’s odd explanatory sentence assumes that his likely readers already know these older gospel traditions, upon which he is about to build further. Specifically, he is reminding them of the foot-washing story that presently exists in Luke, and saying “You know those people? Well I am going to tell you more about them.”

For most of us, the various elements of these stories have become so totally fused that it is hard to recall how separate they were in origin, and how different in the points that different authors are trying to make. For my generation, this is all reinforced by the film of Jesus Christ Superstar, and the “Everything’s Alright” number, sung by Mary Magdalene as she pours “myrrh on your hot forehead.” That song, incidentally, points to a whole other aspect of the story that I will not get into here, namely the post-New Testament evolution of Mary of Bethany to become identical with Mary Magdalene.

Fragrant and Stinking

But what about that doublet I mentioned? Explicit references to smell are not common in the New Testament, except in a sacrificial context, suggesting the savor of sacrifice rising to Heaven. But in this one sequence, John offers us two radically contrasting smell images in a narrative context. According to the KJV, Jesus approaches Lazarus’s tomb:

Jesus said, Take ye away the stone. Martha, the sister of him that was dead, saith unto him, Lord, by this time he stinketh: for he hath been dead four days.

Like other modern translations, the NIV is more genteel:

“But, Lord,” said Martha, the sister of the dead man, “by this time there is a bad odor, for he has been there four days.”

The Greek phrase is “ede ozei,” and implies a smell, usually bad, so “stinks” is legitimate.

Very shortly afterwards, we have a counterpart and reversal of the stink, when Mary anoints Jesus, “and the house was filled with the fragrance of the ointment” (he de oikia eplerotho ek tes osmes tou myrou; ἡ δὲ οἰκία ἐπληρώθη ἐκ τῆς ὀσμῆς τοῦ μύρου).

We should stress how unusual John is here in using smell words in a literal and material sense, rather than metaphorical. His use of ozei is the only one in the whole New Testament, and his use of the “fragrance” word osme is the only such instance in the gospels. It does occur several times in the epistles, but always in a metaphorical sense. 2 Corinthians 2.16 reads “To the one we are an aroma that brings death; to the other, an aroma that brings life. And who is equal to such a task?” In Philippians 4.18, we read, “I am amply supplied, now that I have received from Epaphroditus the gifts you sent. They are a fragrant offering, an acceptable sacrifice, pleasing to God.” Incidentally, the Septuagint Greek text of the Song of Solomon had referred to osme muron, “anointing oils” (the Song in general is the Bible’s “smelliest” book, accounting for eight of the 22 uses of the word “smell” in the KJV translation of the whole Bible).

None of the Synoptic accounts which mention oils or anointing bother to mention its sensory effects, although of course they assume them. To take a specific perfume mentioned, nard was highly aromatic, so much so as to make it worth importing from the Himalayas. The Synoptics had offered a straightforward story of anointing. In John, though, that is expanded by including a “prequel,” the precursor story of Lazarus.

The word “filled” also had a powerful resonance, as this was commonly used in the Old Testament to describe God’s glory “filling” the tabernacle. It comes from a verb that features very frequently throughout all four gospels in the sense of “fulfilling” the scriptures.

But just to focus again on the smells. There are two matched and balanced passages in John, both concerning death. In the first, Lazarus suffers the ordinary death of humanity, which is associated with stench, but Jesus reverses that. In the second, it is in Lazarus’s own house that a woman prepares Jesus for his own death, by means of a glorious smelling ointment that multiply recalls the holiest images of the Temple and its religious practice. The overwhelming perfume of eternal life destroys the stench of death. The house stinks of Heaven. Or to borrow another evocative phrase, it stinks to high heaven.

As with the coal fires, one scene summons images of failure and betrayal; its counterpart symbolizes triumph and glory. Or rather, one smell performs one function, its opposite sends a diametrically opposed message. It was rhetorically necessary for the bad smell to precede the good, for the Lazarus story to precede the anointing – even if that meant a slightly clumsy editorial addition to point to things that had not yet happened.

How many other such doublets and parallels might be found within John?

This post is substantially expanded from one I did here several years ago.