One hundred years ago today, the Tennessee state legislature approved the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, officially ratifying the right of American women to vote. (It was officially certified eight days later.) If, like me, you didn’t already know the suffrage story very well, I highly recommend the new, two-part American Experience episode on “The Vote,” which features commentary from experts like Martha Jones, Elaine Weiss, Marcia Chatelain, and Beth Behn.

Watching that documentary and doing some other reading, I’ve been struck how religion sometimes shaped the motivations and rhetoric of both sides in the suffrage debate. To share just a few examples of the theme…

Religion had been part of the women’s rights movement since before suffrage became its primary objective. In 1848 a “convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of women” was held in the Wesleyan chapel of Seneca Falls, New York. Defying “the circumscribed limits which corrupt customs and a perverted application of the Scriptures have marked out for her,” delegates agreed that woman “should move in the enlarged sphere which her great Creator has assigned her.” That sphere included politics, but also religion. They complained that man allowed woman

in Church as well as State, but a subordinate position, claiming Apostolic authority for her exclusion from the ministry, and with some exceptions, from any public participation in the affairs of the Church… He has usurped the prerogative of Jehovah himself, claiming it as his right to assign for her a sphere of action, when that belongs to her conscience and her God.

As the suffrage campaign gathered strength in the late 19th century, churches and individual Christians bore out historian William O’Neill’s claim that “religion formed the cornerstone of the case against feminine equality.” In 1890, for example, Presbyterians in Virginia concluded that the scriptural “principle of subordination” pertained to “woman’s place, duties, and rights in the home and in the church,” but also “in the state.”

But other Christians supported suffrage, especially those from the more liberal wing of the Protestant tradition. Apart from Elizabeth Cady Stanton, most of the organizers at Seneca Falls had been Quakers, like Lucretia Mott. (Susan B. Anthony was also raised in that tradition.) As leadership of the suffrage movement began to pass to a new generation after 1900, Friends remained influential, none more so than Alice Paul, the young Swarthmore-educated activist who took charge of the push for a federal suffrage amendment in 1912.

In March 1913, Paul organized a historic Woman Suffrage Procession in Washington for the day before the inauguration of President Woodrow Wilson. At least 5,000 women marched down Pennsylvania Avenue, including members of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the Young Women’s Christian Association. (Christianity wasn’t the only religious tradition represented in the procession; the Washington Post noted that the New York delegation carried a banner in Yiddish.) One of the 26 floats in the intricately planned event was dedicated to “women of the Bible lands,” including Miriam, Deborah, and the prophet Huldah.

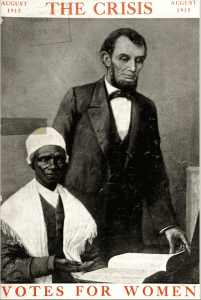

Two years later, one of the most fascinating illustrations of the religious history of women’s suffrage came from members of the movement that its leaders often neglected: African Americans.

Before the Civil War, abolitionism and women’s rights often went hand in hand. But in 1869, Seneca Falls delegate Frederick Douglass had refused to support Stanton and Anthony in their desire to include women in the 15th Amendment, arguing that it was more important to first expand the franchise to include black men. In turn, early 20th century suffrage leaders did not want to lose white support for the 19th Amendment; they pushed black activists like Ida B. Wells to the margins of events like the march in Washington, which Alice Paul decided would be “a purely suffrage demonstration entirely uncomplicated by any other problems such as racial ones.”

But with New York, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and New Jersey preparing to hold referenda on women’s suffrage, W.E.B. DuBois dedicated the August 1915 issue of the NAACP’s magazine to the subject of “Votes for Women.” Once again, religious individuals and arguments played prominent roles. The lead article in The Crisis’ suffrage symposium came from Presbyterian pastor Francis J. Grimké, and AME bishop John Hurst argued that support for women’s rights reflected the impact of Christianity on human civilization:

It discarded and upset the teachings of the past. It gave woman her freedom and womanhood has been lifted to the place where it justly belongs. Christianity established equality and community of woman with man in the privileges of Grace, as being heir together with all the great gifts of life; receiving one faith, one baptism and partaking of the same holy table. It thundering message to all is “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female, for we are all one in Christ Jesus” [Gal 3:28] and the echo of its teachings the world over is to “Loose her and let her go.”

It was African American women themselves who made the most compelling arguments in that symposium. “How can any one who is able to use reason, and who believes in dealing out justice to all God’s creatures,” asked suffragist Mary Church Terrell, “think it is right to withhold from one-half the human race rights and privileges freely accorded to the other half, which is neither more deserving nor more capable of exercising them?”

Two other contributors connected the expansion of political and religious roles for women. “The Negro Church means the Negro woman,” began Nannie Helen Burroughs. “She carries the burdens of the Church, and of the school and bears a great deal more than her economic share in the home.” A leader within the National Baptist Convention, Burroughs had come to prominence in 1900 with an address warning that denomination not to “allow these gems to lie unpolished longer” and instead liberate women to follow their “burning zeal to go forward in [Christ’s] name.” Fellow Baptist Mary E. Jackson (a leader in the NAACP, YWCA, and Wells’ Alpha Suffrage Club alike) buttressed her case for suffrage by pointing out to Crisis readers that “in the ministry 7,000 dare preach the gospel with ‘Heads uncovered.’”

(As Beverly Zink-Sawyer has pointed out, women preachers were doubly significant for the suffrage movement. The pulpit, like the speaker’s platform, “became both the vehicle for the promotion of a political message concerning woman’s equality and a symbol of that message itself by the very embodiment of the speaker’s words in the form of a woman speaking publicly.” From 1904 to 1915, the president of the National Woman Suffrage Association was Anna Howard Shaw, one of the first Methodist women to be ordained.)

Three months later, The Crisis added the dissenting voice of mathematician Kelly Miller, then dean of Howard University. He repeated arguments common to most religious conservatives opposed to granting the “weaker” sex the vote:

Woman’s sphere of activity falls mainly within while man’s field of action lies largely without the domestic circle. This represents the traditional and, presumably, the ideal relation between the sexes. It has the sanction of divine authority and the test of human experience. Woman suffrage could not possibly enhance the harmoniousness of this relationship, but might seriously jeopardize it.

Denying that there was “common ground” between women’s rights and civil rights, Miller concluded on a biblical note: “Male and female created He them; what God has made different man strives in vain to make identical.”

DuBois published Miller’s argument, but rebutted it angrily in his own editorial:

The statement that woman is weaker than man is sheer rot: It is the same sort of thing that we hear about “darker races” and “lower classes”…. The sex of Judith, Candace, Queen Elizabeth, Sojourner Truth and Jane Addams was the merest incident of human function and not a mark of weakness and inferiority.

Estimating that 200,000 black voters would be able to participate in the East Coast referenda, DuBois urged them to support women’s suffrage. To no avail: in November 1915, all four states voted against expanding the franchise to women.

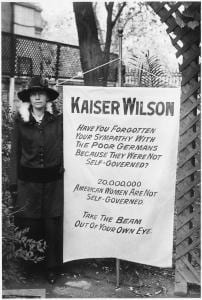

Increasingly, the movement’s energy went into federal action. Carrie Chapman Catt led a massive effort to lobby Woodrow Wilson and members of Congress, and Alice Paul organized a protest aimed directly at a Virginia-born president who insisted that suffrage was a matter of states’ rights. “Resistance to tyranny is obedience to God,” proclaimed a sign held by one of the “Silent Sentinels” who picketed the White House day and night in 1917. “Take the beam out of your own eye,” another told “Kaiser Wilson,” as the United States went to war with Germany.

If only to gain new voters for his party before the 1918 and 1920 elections, Wilson did come out in support of the amendment, which finally cleared the Senate in June 1919. Within a year, 35 of the 36 required states had approved the amendment, with Tennessee looming as the decisive battleground after its Democratic governor reluctantly bowed to pressure from Wilson and called a special session of the state legislature. (The president was “my Moses,” explained Albert Roberts.)

Though the Tennessee senate voted overwhelmingly in favor, the amendment faced a tough battle in the state house. The Chattanooga News reported that “every trick of parliamentary procedure” was used by anti-suffragists like house speaker Seth Walker, whose own speech on August 17th linked white supremacy to male patriarchy. “This is now a white man’s country, and we have a white man’s God,” he thundered, warning that “Hell is going to break loose” if the amendment were ratified.

In the end, the measure passed by a single vote, after a young legislator sheepishly explained that he changed his mind because his mother told him “to be a good boy and help Mrs. Cat [sic] put ‘Rat’ in ratification.”