Alone in the gospels, and in the whole of the Bible, Thomas is eternally remembered for the wrong distinction. He doubted, and that has become his moniker, down through the ages: Doubting Thomas. But his doubt is far from unique, in fact it is universal among the disciples. All of them doubted, every one hard pressed to recognize a reality different from the The End sign written over the death they had witnessed.

Alone in the gospels, and in the whole of the Bible, Thomas is eternally remembered for the wrong distinction. He doubted, and that has become his moniker, down through the ages: Doubting Thomas. But his doubt is far from unique, in fact it is universal among the disciples. All of them doubted, every one hard pressed to recognize a reality different from the The End sign written over the death they had witnessed.

The agony that took them from Jesus’ final hour on Friday to the various hours on Sunday when each of them realized his Easter risenness, was born of doubt and of more than doubt: of disbelief.

Easter did not make sense. It boggled their minds. It became real to them through a series of sensations that could only slowly alter their minds. For those who went to the tomb, the initial sensation of the emptiness was a loss, so convinced were they that death should be present, the death they had witnessed and were expecting to see again.

Next, for Mary, was sight, in which she could not recognize him, even chatted with him a bit, until the sound of his voice, saying her name, became convincing. To recap her Easter journey then: an absence of death; a presence, the voice, none broke through her conviction of death, her disbelief of Easter, until she heard him say her name: a dear word.

For those in the upper room, and on the Emmaus Road, and in the fishing boat, sight was the sense that next befuddled them, confounding their minds with a confusing appearance, and with familiar words in an unfamiliar voice, his authority speaking to them, but they could not discern him in it. The confirming action came through food, its smell, its taste, the sight of it in his hand, him eating, him inviting them to eat, him breaking bread.

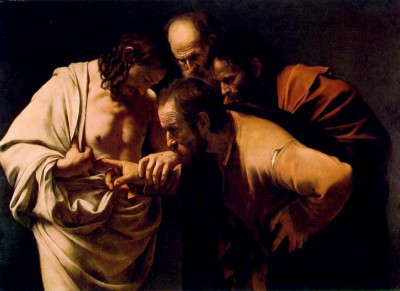

For Thomas, alone, the convincing sense was touch. And he was the only one in all the gospels who touched Jesus ever, after Friday, after he had been laid in the tomb. The reality Thomas sought came through his fingers, more than through his eyes or ears. Thomas the Toucher should be his moniker, in truth.

Perhaps he is not Touching Thomas because of what Jesus said: at the moment of Thomas’ touch and rejoicing, Jesus said, Blessed are those who have not seen, and yet believe. So for Jesus the issue at hand was not the sensory road by which Easter is received, but where the focus of the senses lay. His death wounds were what Thomas touched, what Thomas expressly said he needed to touch to know Easter.

Blessed are you who have not seen and have believed. It is not death that gives Christ’s Easter life its power. Nor is it death that authenticates Jesus’ journey onto the cross or into Easter. Love’s redeeming work is the focus upon which we are to be fixed – the cooking of breakfasts, the sharing of anguishing news along the road, the moment of greeting in the garden.

Blessed are you who have not seen and have believed. It is not death that gives Christ’s Easter life its power. Nor is it death that authenticates Jesus’ journey onto the cross or into Easter. Love’s redeeming work is the focus upon which we are to be fixed – the cooking of breakfasts, the sharing of anguishing news along the road, the moment of greeting in the garden.

For many, his wounds remain a fixation. In our doubt, they are questioned as non-lethal, or a fiction. As if violent wounds were a fiction in human experience rather than a routinely common occurrence born of human hate. In our belief, they are sometimes worshipped with a fixation that insists on a superlative degree of torture detail here, a unique reality which denies the gospels’ claim that Jesus died a routinely common death administered to slaves and the very poor.

![]() How much of each night’s news is fixation upon the gory details – the power of death. And survival, never detailed very much, is greeted as an escape from death’s power rather than the power of love’s redemptive work. Love’s work is nice, in our estimation, but does not have the fascinating power of death. Thomas, whose name means twin, stands alone in the gospel. Perhaps we are his twin, each of us standing in his shoes, asking to touch the wounds in which life became unsustainable, more inclined toward knowing the power that fascinates us, than the power that liberates us.

How much of each night’s news is fixation upon the gory details – the power of death. And survival, never detailed very much, is greeted as an escape from death’s power rather than the power of love’s redemptive work. Love’s work is nice, in our estimation, but does not have the fascinating power of death. Thomas, whose name means twin, stands alone in the gospel. Perhaps we are his twin, each of us standing in his shoes, asking to touch the wounds in which life became unsustainable, more inclined toward knowing the power that fascinates us, than the power that liberates us.

Lord, help our unbelief! ______________________________________________________________ Illustrations:

1. The Incredulity of St. Thomas, by Caravaggio, Neues Palais in Sanssouci, Potsdam, Germany. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

2. The Incredulity of St. Thomas, Duccio di Buoninsegna, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Siena, Italy. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

4. The Good Unbelief of St. Thomas, detail. Icon in the Iconostasis of the Monastery of St. Cyril. Google Images.

5. Doubting Thomas, 16th c. Greek Orthodox Icon. Google Images.