According to John: Jesus, in many speeches, prepares those he loves for his impending departure by naming the things he will leave behind – his legacy. Peace I leave with you, he says, on Easter Day and often after. His love, hope, joy. These are an inheritance he transmits. Repeatedly, he names The Truth as what he lives in always, as what he gives to them and as what the Advocate (the Spirit) will give them always.

According to John: Jesus, in many speeches, prepares those he loves for his impending departure by naming the things he will leave behind – his legacy. Peace I leave with you, he says, on Easter Day and often after. His love, hope, joy. These are an inheritance he transmits. Repeatedly, he names The Truth as what he lives in always, as what he gives to them and as what the Advocate (the Spirit) will give them always.

The Truth, Jesus tells them, will prove the world is wrong about sin and righteousness and judgment. Wrong about sin, because the world does not believe Jesus, or anyone, can offer forgiveness. Wrong about righteousness, because Jesus’ rising, at Easter, and again now at the Ascension, are acts of justice that the world cannot see and so disbelieves, instead thinking that justice was what they could see: the power of the ruler who put him to death, and the power of the charges for which he was put to death. And, Jesus continues, the world is wrong about judgment, because the ruler of this world has been condemned, in this world, by his false judgment and his injustice and lack of mercy.

This week, the jury empaneled to decide the fate of the surviving marathon bomber, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, sentenced him to death, for four murders , dozens of maimings, hundreds of shrapnel and other injuries, including persistent deafness in many from the noise of the bombs. They felt that he showed no remorse in his months of sitting before them while the testimony of these injuries was given.

This week, the jury empaneled to decide the fate of the surviving marathon bomber, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, sentenced him to death, for four murders , dozens of maimings, hundreds of shrapnel and other injuries, including persistent deafness in many from the noise of the bombs. They felt that he showed no remorse in his months of sitting before them while the testimony of these injuries was given.

There was no argument about his guilt: his lawyers admitted that from the start, and we had all seen the ubiquitous videotapes that showed us Dzhokhar Tsarnaev and his brother in the crowd, placing their bombs behind the Richard family and their three children, returning to the subway as if nothing were on their minds. The jury was given strict instructions for making decisions on each charge, and I have no doubt these were legally framed.

But missing from all this was the consideration of the Truth Jesus speaks about, that proves the world wrong about sin and righteousness and judgment. From the man on the street to the jury in the court, the common argument was that forgiveness was impossible here. Even Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s lawyers agreed with that. And for many there was accord that the ’righteousness’ (meaning: justice) in this situation was the penalty of death.

But missing from all this was the consideration of the Truth Jesus speaks about, that proves the world wrong about sin and righteousness and judgment. From the man on the street to the jury in the court, the common argument was that forgiveness was impossible here. Even Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s lawyers agreed with that. And for many there was accord that the ’righteousness’ (meaning: justice) in this situation was the penalty of death.

There were some exceptions: polls of Boston’s citizens were overwhelmingly in favor of life in prison rather than death (polls of the nation, though, were more than two thirds for death); and some notable Catholic laity, the Chief of the Boston Police, for one, and the family of Martin Richards, the boy who died, whose sister and mother were badly injured , whose brother has PTSD and whose father has shrapnel wounds and some hearing loss, declared that not only their faith, but also their peace of mind, needed a sentence of life in prison.

One lonely Catholic keeping vigil outside the courtroom, an Iraq war vet, said No one should be sentenced to death for the worst day in his life, echoing Jesus’ assertion that the world is wrong about judgment.

One lonely Catholic keeping vigil outside the courtroom, an Iraq war vet, said No one should be sentenced to death for the worst day in his life, echoing Jesus’ assertion that the world is wrong about judgment.

There was a battle in the court over allowing anti-death-penalty nun, Sr. Helen Prejean, testify. In the end, she was allowed to speak to questions about her visit with Tsarnaev, but not to speak about the Truth as she understands it, not to speak about mercy, justice, judgment, or the Truth of the Spirit of Jesus.

There was complaint among many that Tsarnaev showed tender feelings only once, when his elderly aunt, who had travelled from Russia to speak about his childhood, was so overcome with panic and hyperventilation that she could not speak. Tears came to his eyes, and he sobbed once. And people said, he only had tears for himself. But his tears were really for her, it seems to me, and in her he had to face the Truth, that what he and his brother thought they were doing for justice for her and her people, had actually caused her great pain.

Belief in Dzhokhar’s common humanity; belief in the possibility of his human transformation; belief that, at 21, he could still grow in spirit and in heart; belief that he is a child of God; belief in his sorrow, for all that he has lost that he did love; even belief in the community of those he grew up among, who liked him then: all these beliefs were pushed away. The scrum of reporters covering the trial declared these things unconvincing.

Belief in Dzhokhar’s common humanity; belief in the possibility of his human transformation; belief that, at 21, he could still grow in spirit and in heart; belief that he is a child of God; belief in his sorrow, for all that he has lost that he did love; even belief in the community of those he grew up among, who liked him then: all these beliefs were pushed away. The scrum of reporters covering the trial declared these things unconvincing.

We are accustomed to proclaiming that Jesus committed no crime; but what he wanted us to see was his insistence that no one should be destroyed, that he embraced the guilty man beside him and the guilt in us all, offering the thing we ruled inadmissible here in Boston, belief in redemption.

Well, now we have to live with what has been done.

Frederick Buechner, some years ago, wrote:

Does the Spirit of God move over the face of the turbulent waters of our age? The Hebrew word for “move”, merahepeth, means to “brood” as a bird broods over its nest until finally new life begins to stir beneath the sheltering wings. Is new life stirring in this death-ridden world? Is light about to be created out of our darkness? This is the only question that matters. And this is the question before us, at Pentecost.

_____________________________________________________

Illustrations:

1. Pentecost, by the Rohan Master, 1340. Bibliotheque Nationale de France, Paris. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

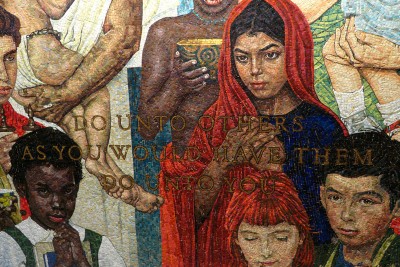

2. The Golden Rule, 1985 Mosaic in the United Nations, based on a painting by Norman Rockwell. UN, New York. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

3. Knocking on Heaven’s Door. Freestanding Sculpture by Kinga Dunikowska – Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition

4. To the Pentecost, Sergei Korovin, Tretiakov Gallery, Moscow. 1902. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.

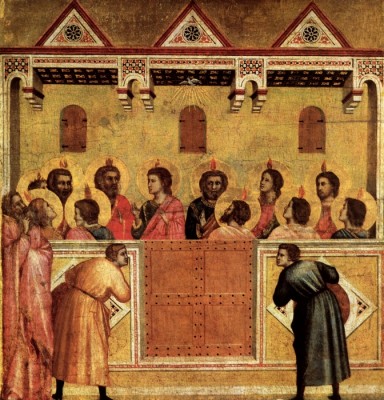

5. Pentecost. Giotto di Bondone, 1320-25. National Gallery, Great Britain.

5.