It was right after I’d submitted the final manuscript proofs to the publisher for my third book, Feminism and Christianity, that I admitted to my Facebook friends that I was antsy without a big book project. Wondering what was next. Feeling adrift.

My friend Krista simply commented, “Remember sabbath.”

Oh. Yeah. That sounds familiar.

Sabbath. That religious practice of sacred time. Time set apart from the ordinary, time for worship, reflection, prayer, rest, and gratitude. It’s something found in many religious traditions, including Christianity. As the fourth in my series of posts “Getting Theological,” this one is framed not with the words of other thinkers or the tradition itself, but framed with experience and daily life. {Here’s another blogger writing on sabbath, a former student of mine, Jeff Goins.}

When Krista nudged me to “remember sabbath,” it was during my first sabbatical. It’s one of the privileges of a job as a tenured professor. Every seven years we can apply for a semester or a year away from the classroom, with full or partial pay. The purpose is manifold: scholarly productivity, pedagogical innovation, research and travel, and oh yes, rest. I found it alternately ironic and painful that my sabbatical was in the spring semester of 2009, which you may recall as the peak/valley of the great recession. All around me, family and friends losing jobs, struggling to keep their homes, and having to relocate. On the news every day a wildly bouncing stock market and social volatility that made everyone jumpy.

And I’m on sabbatical? Reading, writing, travelling, speaking … keeping busy but in ways that only I truly controlled. And enjoyed. And reckoned with the social privilege that my life reflected in so many ways. This time set apart from anxiety and rollercoaster-existence.

More recently, on an airplane on the way home from a trip west to visit family, I took this picture. Where the traditional “No Smoking” sign has traditionally glowered at travelers, warning them against disobedience under penalty of federal law, were the words: Turn off electronic devices. I had never seen it before, and haven’t since. But it’s perfect.

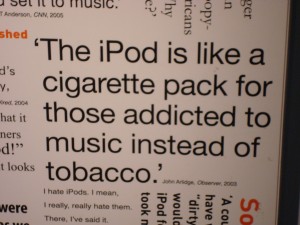

It reminded me of this picture, taken at the Science Museum in London during our trip there in 2009 (that sabbatical travel again).  It was part of a large display about the invention of the iPod. Seeing how “No Electronic Devices” has replaced “No Smoking” makes it official: The iPhone is the new cigarette. We’ve replaced one little addictive package with another. A new way to keep ourselves busy, occupied, fixated, addictively connected.

It was part of a large display about the invention of the iPod. Seeing how “No Electronic Devices” has replaced “No Smoking” makes it official: The iPhone is the new cigarette. We’ve replaced one little addictive package with another. A new way to keep ourselves busy, occupied, fixated, addictively connected.

But, what do you do when you are prohibited by federal law from using your cell phone or laptop? I’m usually a paper-book-reader person, so I always have a physical book or magazine to read. (I’m also a don’t-talk-to-me-traveler when solo, and burying my nose in a book is a great way to ignore the person to whose thighs I am inevitably adjacent.)

But when faced with the iPhone-as-cigarette light (which I decided to call it), what do others do? On that flight, some closed their eyes, others talked to the person next to them, a few flipped through the airline magazine. Several looked out the window, while others rummaged through a bag, or ate a snack, or actually watched the flight attendants instruct us on what to do in case of a water landing in the middle of Kansas.

It’s a little sabbath, isn’t it? Taking time to look out the window. Talk to your neighbor. Close your eyes and be quiet. Pray? Read something – on paper. Sleep. Eat something because you’re strapped in with no place to go. Things we don’t normally do because we’re attached to our devices and our busyness.

The Jewish and Christian traditions of sabbath offer this. Sacred time, time set apart, to not do what we are daily consumed with. Biblically, it is connected to the first creation story in Genesis. When “God blessed the seventh day and hallowed it, because on it God rested from all the work that he had done in creation.” (Gen. 2:3). Judaism and Christianity have scheduled this differently, as Friday/Saturday between sunsets for the former, and Sunday for the latter. Historically, the practice of sabbath has shifted. For some times and traditions, it has meant not working at all, and conducting no business that would require others to work.

But today, a very few of us are able to have long stretches of time, even 24 hours between sunsets, with no working and no doing of business, no errands and no chores. Some states still have remnants of ways that this used to be broadly legislated, they were called blue laws. Businesses were not allowed to open on Sunday. Everyone was expected to keep the sabbath. Liquor laws are a most obvious way to see how the impact of this still exists today. In Indiana, you can’t buy any alcohol on Sunday (which we were vexed to learn on one Sunday grocery run early in our years living there), and in my central Illinois town just recently the city council voted to move up the time that you’re allowed to buy booze from noon to 9am on Sunday.

Whatever it is consumes our ordinary time, sabbath offers us a time away from it. In a twenty-first century life, though, I keep returning to the fact that the ability to engage in sabbath is in itself a fruit of privilege.

Must it be so?