I’m getting close to finishing Michel Houellebecq’s novel Submission. The critics immediately billed the book as a tale about Islam when it was released right after the Charlie Hebdo massacre (totally unplanned). I’m not convinced.

That’s not the impression I get at all. Even though the plot revolves around the takeover of France by what (200 pages into the book) still looks like a moderate Muslim government, that government takes its inspiration from the Roman Empire and medieval Catholicism. Its fiscal policy does not come from Islamic economics (yes, there is such a thing), but from the Distributism of Chesterton, Belloc, and the popes. Weird and classically Catholic stuff that is.

The narrator of the book, Francois, is a Huysmans scholar who not only cannot embrace religious belief in his own life, but he comically cannot even understand the religious preoccupations of the late Catholic works of his main topic of study: Huysmans.

Yet, Francois finds himself–between running from his past and the anxieties caused by the drastic change in government–continually returning to sacred places Huysmans visited. These give Francois brief, all too brief, relief from the postmodern anxiety and despair that drowns out his will to live (and the lives of so many other Houellebecq characters).

However, since he is such a paradigmatically superficial character–a postmodern Everyman tired of the academic career he left behind, increasingly unsatisfied with high-class escorts, and compulsively observing the natural breakdown of his body– when he has moments such as the following at Rocamadour the contrast makes them stand out all the more:

Every day I went and sat for a few minutes before the Black Virgin [for closeups click here]—the same one who for a thousand years inspired so many pilgrimages, before whom so many saints and kings had knelt. It was a strange statue. It bore witness to a vanished universe. The virgin sat rigidly erect, her head, with its eyes closed, so distant that it seemed extraterrestrial, was crowned by a diadem. The baby Jesus, who looked nothing like a baby, more like an adult or even an old man–sat on her lap, equally erect; his eyes closed too, his face sharp, wise, and powerful, and he wore a crown of his own. There was no tenderness, no maternal abandon in their postures. This was not the baby Jesus; this was already the king of the world. His serenity and the impression he gave of spiritual power–of intangible energy–were almost terrifying.

Submission then makes some fine distinctions about the development of theological pluralism in the Middle Ages:

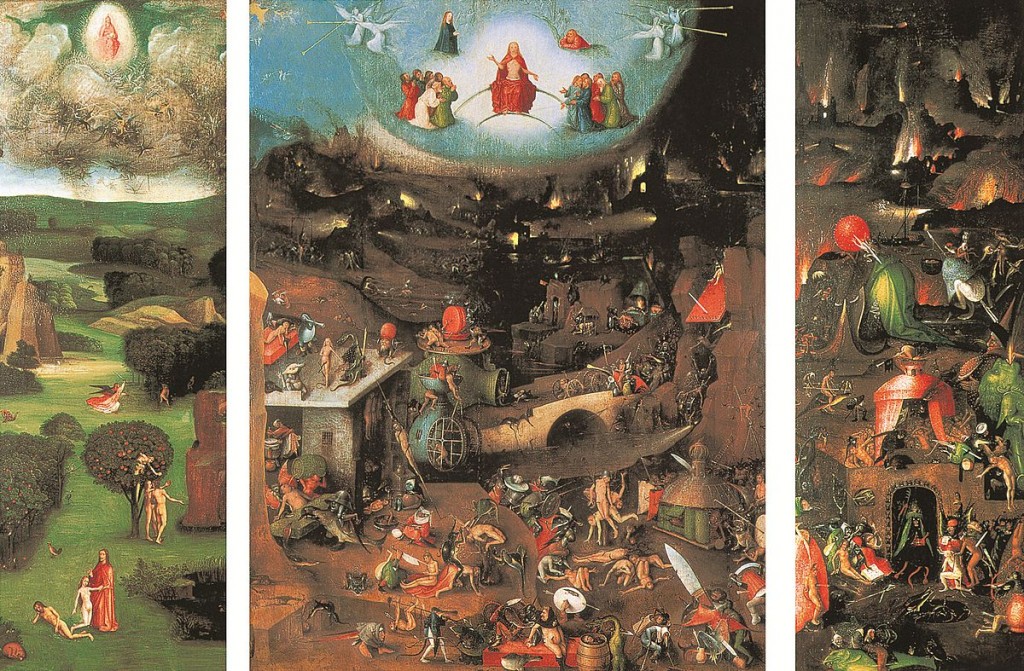

This superhuman image was a world away from the tortured, suffering Christ of Matthias Grunewald, which had made such a deep impression on Huysmans. For Huysmans the Middle Ages meant the Gothic period, really the late Gothic: emotionally expressive, realistic, moralizing, it was already closer to the Renaissance than to the Romanesque…. In the early Middle Ages . . . the question of individual judgment barely came up. Only much later, with Hieronymus Bosch, for example, do we see those terrifying imagaes in which Christ separates the cohort of the chosen from the legion of the damned; where devils lead unrepentant sinners toward the torments of hell. The Romanesque vision was much more communal…

Submission is not only a glimpse into the future, but it also serves as a good introduction to the continually vibrant spiritual energy of the recent French Catholic past of Leon Bloy, Paul Claudel, Georges Bernanos, and Huysmans.

Some of these towering figures are covered in Jazz Age Catholicism: Mystic Modernism in Postwar Paris, 1919-1933.

You might also want to take a look at the following related articles: Houellebecq: Charlie Hebdo Coverboy Maps Faith’s Manifestations and Michel Houellebecq’s Submission to Catholicism.