Back in 2007, right when I was starting this blog, a ground breaking study revealed an extra-ordinary finding. What the researchers had discovered was that just giving people subliminal reminders of religion was enough to make them be more generous in a something called the dictator game.

The really extraordinary thing was that the same effect was seen in both religious and non-religious people.

When I blogged about it at the time, I was a little sceptical about that. It seems that Cristina Gomes and Mike McCullough at the University of Miami were a little sceptical as well, because they decided to replicate the study to see what results they got.

The setup was pretty simple. They asked their subjects to unscramble some sentences. Just as in the original study, some of the subjects received jumbled sentences with religious phrases, and some received only secular phrases. In a twist to the original, in the new study they also gave some subjects secular phrases with religious words in to unscramble (like: “dessert divine was fork the”).

The idea is that the subjects who unscrambled the phrases with religious words would be subliminally reminded of religion, and change their behaviour as a result.

As a simple test of generosity, the researchers then gave their subjects ten dollar notes and told them that they were free to leave as much or as little as they wanted, anonymously, to a future participant.

The result: the religious primes had absolutely no effect.

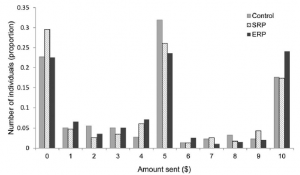

The graphic shows the distribution of how much was given. You can see that about a third gave nothing, a third gave $5, and third more ultra-generous individuals gave over the full $10.

The graphic shows the distribution of how much was given. You can see that about a third gave nothing, a third gave $5, and third more ultra-generous individuals gave over the full $10.

The different coloured bars shows each of the three different sentence types people received. Looking at it you might think there are a few differences, but statistically they are meaningless. Not only that, but even looking at, for example, religious versus non-religious, or rich versus poor, or men versus women, gave the same negative results.

Now, there are several possible explanations for why Gomes and McCullough got different results from previous researchers. Their subjects weren’t university students, and they were more culturally and socially diverse (and more generous!).

But in my opinion the most likely factor was simply that they included far more people in their experiment.

The original experiment was rather small – only 50 people. And it fell short on statistical rigour for a number of reasons. It’s possible that what seemed that a statistically significant effect was just the result of chance.

Gomes and McCullough make all these points. But the clincher for me comes in another analysis they put in their paper. They did what’s called a ‘meta-analysis’, pulling together all the different results from similar studies to get an idea of what the big picture looks like.

They point out that the big picture suggests that there really is nothing to see here. But when I look at the figure they present it screams something else to me: publication bias.

Publication bias happens when people do lots of small studies, but only publish the ones with positive results. Often that’s done with the best of intentions. After all, there’s any number of reasons why a study might fail, and journal generally aren’t interested in negative results.

But of course if there was no real effect to be seen then you’d expect some experiments to come out negative and some positive, just by chance. When publication bias is at work all the small studies that get published look positive – the negative ones are missing. It’s only when someone does a big study that you get the convincing negative result.

And that’s exactly what Gomes and McCullough’s meta-analysis shows. A bunch of small, positive studies and one big negative study.

I suspect that much of the discussion about the subliminal, pro-social effect of religion may have been a case of smoke and mirrors.

That doesn’t mean that the effect doesn’t occur. After all there’s plenty of evidence from other studies that being in a religious environment can change behaviour – sometimes in unexpected ways (see this and this and this, for example) But it seems that a simple task of giving people sentences with religious words in is not enough to change their behaviour.

Incidentally, they did find that women gave more than men, and English Speakers gave more than Spanish speakers. But that fascinating finding is out of scope for this blog!

![]() Gomes, C., & McCullough, M. (2015). The Effects of Implicit Religious Primes on Dictator Game Allocations: A Preregistered Replication Experiment. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General DOI: 10.1037/xge0000027

Gomes, C., & McCullough, M. (2015). The Effects of Implicit Religious Primes on Dictator Game Allocations: A Preregistered Replication Experiment. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General DOI: 10.1037/xge0000027