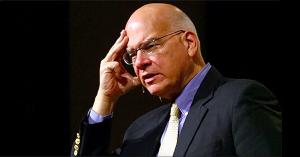

In the penultimate chapter of his Reason for God, Tim Keller attempts to pull together all the loose threads strewn about this apologetic work, weaving them together into a coherent vision for the world. He offers his belief system as a superior alternative to the one the rest of the world wants you to accept, as if the myriad belief systems around the globe could be boiled down to a single alternative, variously disguised.

In the penultimate chapter of his Reason for God, Tim Keller attempts to pull together all the loose threads strewn about this apologetic work, weaving them together into a coherent vision for the world. He offers his belief system as a superior alternative to the one the rest of the world wants you to accept, as if the myriad belief systems around the globe could be boiled down to a single alternative, variously disguised.

That’s an unsurprising assumption, I suppose, if you believe that a single sinister intelligence secretly operates underneath every nation and religion outside of your own. I remember seeing the world in such black-and-white terms. Everything was so much simpler that way.

Misunderstanding Humanism

My chief complaint about Keller is that he conveniently misrepresents the alternatives to his own perspective, framing the discussion according to whichever issues that he believes this faith resolves, meanwhile presenting his own tradition in an idealized light. Most of us know better though, because we’ve been there and done that. We even have the t-shirts to prove it.

Keller has a really bad habit of viewing the world in binary terms, as if every choice you make boils down to either self-interest or “other” interest, selfish greed or self-giving love. In Keller’s mind, everything outside of Christianity orients you inward toward your self, hollowing you out through a vain preoccupation with navel-gazing, self-admiration, and self-service. It makes us all what C.S. Lewis called “men without chests.”

In particular Keller seems unable to grasp the communal aspect of humanism, a perspective on the world in which the center of everything is not the individual, but the whole community, and ultimately the entire human race. I would argue, in fact, that a mature humanism will encompass the best interests of our entire ecosystem, perhaps eventually rendering the word human-ism obsolete. But first things first.

Keller doesn’t get that humanism isn’t about the self vs. the other—it’s about a balance between the needs of both. That’s what’s needed for healthy human relationships, and for living fulfilling, purposeful lives.

Reasonable or Not? Please Choose One

Sharing the gospel with someone like me is like trying to convince a woman to go out with a man whom she recently divorced after twenty years of marriage. Bless their hearts, they mean well. They just have no idea how over it we are.

We’ve seen both the good and the bad, so it rings hollow for us when Keller gives us an idealized presentation of what it has to offer. The Christian faith makes such grandiose claims, but we’ve been around the block one too many times to fall for the sales pitch. We ourselves have been on the inside—we’ve even stood in his position, offering this faith to others with the same appeals to human vulnerabilities—so we know exactly where and how it fails to deliver.

Christianity makes the most sense out of our individual life stories and out of what we see in the world’s history. (p.222)

I remember feeling that way, too. I would have agreed with him a little over a decade ago. But time and experience have taught me that Keller’s interpretation of each requires exaggerating the virtues of his own tradition while magnifying the vices of everyone else’s. For example, in Chapter Four his recounting of progressive social movements in American history (e.g. abolition, civil rights) unforgivably downplays the very public and demonstrative way that his own conservative theological tradition resisted every forward step along the way.

Read: “Whitewashing Christian History in The Reason for God“

Keller also claims that his belief system uniquely resolves the philosophical dilemmas that plague other religions and philosophies, like the problem of “the one and the many.” Like many before him, he believes that the doctrine of the Trinity—the notion that God can be both singular and plural at the same time—enables God to be simultaneously alone and yet never alone. He can be driven by pure self-interest, demanding that everyone else in existence orient themselves around his desires as well, while still remaining above the charge of selfish conceit, since in adoring himself he is also adoring at least two other people, or “persons,” or whatever.

This just doesn’t make any sense, though. Theologians and ministers revel in the contradiction of God being three-in-one, as if holding incoherent ideas like this were positive evidence that human beings cannot have made this up since it makes so little sense. Keller openly admits to the irrationality of it all:

The doctrine of the Trinity overloads our mental circuits. Despite its cognitive difficulty, however, this astonishing, dynamic conception of the triune God is bristling with profound, wonderful, life-shaping, world-changing implications. (p.225)

Notice how he begins this chapter by saying Christianity “makes the most sense” of our lives but then three pages later says it “overloads our mental circuits.” So which is it? Does it make sense or doesn’t it? Is his a reasonable faith or is it not? And are we not allowed to demand that a “reasonable faith” at least not violate the law of non-contradiction?

It seems to me they want to have their cake and eat it, too. They want the Christian faith to be intellectually respectable (thus a book entitled “Reason for God”) but then they ask that we put aside our need for logical consistency whenever a Christian doctrine violates one of the most basic principles of logic (e.g. a thing cannot be both A and not-A at the same time). They keep telling us that “all truth is God’s truth,” and that he created us with a brain he intends for us to use. But whenever our study of the world around us contradicts what this religion tells us is true, we are told we must trust God with all our heart and “lean not on our own understanding.” Suddenly our God-given brains are an encumbrance.

This belief that things don’t have to make sense wears down the irony meters of millions of people week after week. And how could it not? Every Sunday morning Christians are told that God is both everywhere and nowhere, that he is one but also three, that he loves everyone but plans on torturing most of them after they die (or allowing them to torture themselves, if they believe in Hell 2.0), and that he will give you everything you truly need…but that for some reason you still have to ask him for it, and he may also withhold it just to make you trust him more.

No wonder politicians can get up in front of them and make mutually exclusive promises without ever getting called out for the contradictions. Their belief in the supra-rationality of the Christian faith enables charlatans of every stripe to lead large numbers of them wherever they please. If things don’t have to make sense, you can be made to believe anything. What a golden opportunity for hucksters like Donald Trump.

Four Promises That Fail to Materialize

Here at the end of the book, Keller keeps trying to sweeten the deal, piling claim upon claim that exvangelicals like me know aren’t legit. By my count there are at least four promises in this chapter that have failed to match up with real life.

- God is full of joy, and worshiping him will bring YOU joy and fulness, as well.

On page 225, Keller paints a picture of a “God [who] is infinitely happy,” overflowing with joy, compassion, creativity, and selflessness, but he does so by citing puritan preacher Jonathan Edwards, of all people, who authored the famous sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” fueling the nightmares of children for hundreds of years since.

He describes the relationship between the three persons of the Trinity, as well as between humanity and divinity, as a kind of joyful dance. I find it ironic that he does this even after his own evangelical tradition distinguished itself in this country as the enemies of dancing, partying, and drinking alcohol (someone forgot to tell Jesus about that one). Truth be told, they’re only cool with this dancing imagery so long as it’s purely a metaphor.

Ever seen the movie Footloose? It was the evangelical churches in Elmore City, Oklahoma, who made sure their little town didn’t have any dances from its incorporation in 1898 until 1980. In the real life story, it was a rancher, not a preacher, who finally broke the tie in the school board’s decision to lift the antiquated prohibition of dancing within the city limits. To this day, my family’s church tradition still frowns upon dancing as a vulgar and dangerous pastime to be avoided as much as possible.

Keller’s tradition is a restrictive, austere, self-denying one that is too busy prohibiting the things that make us feel alive to notice they’ve forgotten to major on the things Jesus really majored on, like helping the poor and welcoming people who are different from them. In my experience it doesn’t inspire art or creativity, it stifles it.

- Because God is selfless and self-giving, centering your life on him is in your best interests.

Another thing Keller’s Christianity promises is that the only way to live your life to the fullest is to give it up, in a way, willingly surrendering your own interests in order to pour your energies into what God wants from you instead. According to Keller, God is the kind of being who can demand absolute and unrivaled worship without being selfish or egotistical at all:

“He has infinite happiness not through self-centeredness, but through self-giving, other-centered love. And the only way we, who have been created in his image, can have this same joy, is if we center our entire lives around him instead of ourselves. (p.227)

…If we will center our lives on him, serving him not out of self-interest, but just for the sake of who he is…we will enter the dance and share in the joy and love he lives in. (p.228)

According to Keller, God is so selfless that he can demand our utmost praise and adoration without opening himself up to the same charges of egotism that this belief system declares we ourselves deserve. And yes, that’s inconsistent, but remember that his ways are higher than your ways, his thoughts higher than your thoughts, so you don’t get to judge for yourself whether or not this makes any sense. Maybe it’s not special pleading if it’s not a request at all, but a command.

In my experience, losing your self and surrendering your will to God does not produce life or joy or happiness, Taking up your cross to follow him isn’t at all what it’s cracked up to be. I tried it for myself for many years and found out first-hand that the things you sacrifice for the glory of God stay dead—there is no resurrection on the other side. There isn’t any divine deliverance or restoration on the other side of getting crucified, either literally or metaphorically. But don’t take my word for it, try it for yourself and see what happens.

- Orienting your life around Jesus will bring healthy relationships with other people.

In all fairness, sometimes this is true. Some people really do need Jesus. I suspect there are many families who would be much worse off were it not for the Christian tradition teaching them better ways to act and speak toward each other. I’ve known my share of men who would be far less tolerable husbands and fathers if their churches didn’t impress upon them a sense of responsibility for treating their families well, providing for them and leading them with a servant’s heart. Yes, religion makes some of them worse. But it also makes some of them better than they would be without it.

He invites you to begin centering everything in your life on him, even as he has given himself for you. If you respond to him, all your relationships will begin to heal. (p.230-231)

Now that’s definitely pushing it. I know too many friends who were hurt by their parents, by their pastors, or even by their friends who were just trying to straighten them out according to the way their church believes a person should live. Written as it was in another time and place, the Bible can be used to justify barbaric mistreatment of others, depersonalizing women and foreigners depending on where you look. It heavily stresses submission to authority, and it was written during a time in which women were still being seen as property.

In the end, faith is fragile and it has to protect itself, and if that has to happen at the expense of even the most important relationships you have, then it will do whatever it must to preserve itself. And don’t try to tell me that’s not what Jesus would have wanted because that’s exactly what he said following him requires.

- The Christian message uniquely instructs us to care for the environment, and to fight for social justice as well.

This one actually made me laugh out loud. It takes a great deal of hermeneutical gymnastics to tease out a concern for the environment from the New Testament, and you won’t hear many evangelical pastors impressing upon their congregations that caring for the ecosystem is on the God’s wish list for his people.

The work of the Spirit of God is not only to save souls but also to care and cultivate the face of the earth, the material world. (p.233)

…Christians become stewards of the material world, from those who cultivate the natural creation through science and gardening to those who give themselves to artistic endeavors, all knowing why these things are necessary for human flourishing. (p.235)

Science and gardening? Artistic endeavors? Are these the things you see evangelicals focusing on at all? This is laughably absurd. But what would you expect? There is virtually nothing at all in the pages of the New Testament which would communicate to the church today that God wants them to focus on developing these things.

Historically speaking, the church’s relationship to science is antagonistic more often than not (try showing Cosmos in an evangelical church sometime). And most artistic expression coming out of the church consists in taking things “the world” has come up with and changing a thing or two to make it “Christian.” It is many things, but it isn’t “art.”

And as for environmentalism, if anything evangelical churches view it as a distortion of priorities, as if being concerned for the limits of our planet’s natural resources represents a kind of idolatry. It’s planet worship, the way they see it. It signals a failure to trust that God is in control, and that he will never let anything truly awful happen to our ecosystem that he doesn’t want to have happen. Again, don’t take my word for it. Just try to bring up a concern for climate change in an evangelical church and see how they take it.

Justice for Whom?

Keller’s inclusion of social justice merits special mention, especially during a moment like the one we’re living in right now:

The story of the gospel makes sense of moral obligation and our belief in the reality of justice, so Christians do restorative and redistributive justice wherever they can. (p.235)

I wish they would. Maybe they will again someday, but today’s evangelical Christians have been taught to view cries for social justice as a diversion from their real mission, which is saving souls. Keller’s tradition cares much more about what happens to us after we die than it does about what happens before, save for telling us to quit looking at porn or whatever. They see their role in the world as one of “Designated Adult,” as Captain Cassidy so perfectly calls it. If only that role included taking responsibility for things like an unequal distribution of justice, of education, and of economic opportunity.

Their feelings about race are evident in their vehement disapproval of Critical Race Theory, an academic tool they don’t understand but know they are supposed to hate because everyone they trust says it’s pure evil. The leaders of the largest evangelical denomination in the world denounced it by name last year, and then a few weeks ago during their large annual meeting the denomination almost split over whether or not it should even continue to be a discussion.

Evangelical theology frames almost all responsibility in personal, individualistic terms. It demands that each person must make their own profession of faith because salvation is personal, a matter strictly between you and God. The institutions and systems we live in can help or hurt this goal, but those institutions will not survive the second coming of Jesus, who will almost certainly burn it all to the ground before starting something new. You don’t polish brass on a sinking ship.

Structural sin doesn’t exist in evangelical theology, so there’s nowhere to put concerns for things like this. How can an institution or system be racist if your worldview defines racism in strictly individual terms? It’s impossible. There can only be racist individuals, not racist institutions. Certainly not racist churches or racist theology.

Keller’s sales pitch is beautiful in places, but dishonest. I wish what he were selling were true, but it’s not. And I know this the same way so many others like me know it: We’ve been there, and we’ve done that. We’ve watched how this plays out in real life, not on paper, where you can make all the ideas seem like they mesh together into a coherent whole. We’re just not buying it.

[Image Source: New Calvinist]

__________

(Other Posts in this Series)

- Introduction: “Revisiting Tim Keller’s The Reason for God“

- Chapter One: “Christian History, Revised“

- Chapter Two: “The Problem of Evil in The Reason for God“

- Chapter Three: “Straw Skepticism and The Reason for God“

- Chapter Four: “Whitewashing Christian History in The Reason for God“

- Chapter Five: “The Evolution of Hell in The Reason for God“

- Chapter Six: “Believing in Evolution, But Not Too Much“

- Bonus: “What’s Wrong with Asking for a Miracle?“

- Chapter Seven: “For the Bible Tells Me? No.“

- Intermission: “Changing Gods Midstream“

- Chapter Eight: “Four (Bad) Reasons for God“

- Bonus: “The Argument from Misunderstanding Evolution“

- Chapter Nine: “Tim Keller and the Argument from Morality“

- Chapter Ten: “Why Everything You Do Is Wrong“

- Chapter Eleven: “Your Religion Is Special, Just Like All the Others“

- Chapter Twelve: “But Why Does There Have to Be Blood?“

- Chapter Thirteen: “Seven Bad Arguments for the Resurrection of Jesus“

- Chapter Fourteen: “Four Ways Tim Keller’s Gospel Falls Flat“

- Epilogue: “Why the Gospel Doesn’t Work on Exvangelicals

__________

If you’re new to Godless In Dixie, be sure to check out The Beginner’s Guide for 200+ links categorized topically on a single page.

And if you like what you read on Godless in Dixie, please consider sponsoring me on Patreon, or else you can give via Paypal to help me keep doing what I’m doing. Every bit helps, and is greatly appreciated.

You can also follow the Godless in Dixie Facebook page: