Writing the Foreword for Gregg Ten Elshof’s For Shame was a challenge. Why? Because forewords have to be short, and I could hardly contain my enthusiasm after reading his book. For Shame is a genuine contribution to recent discussions about shame. Although a short read, it will doubtless stir serious debate.

Ten Elshof doesn’t shy away from controversy, but not for the sake of provocation itself. Rather, he presses readers to expand their understanding of shame while considering its theological and practical ramifications.

Ten Elshof doesn’t shy away from controversy, but not for the sake of provocation itself. Rather, he presses readers to expand their understanding of shame while considering its theological and practical ramifications.

In my opinion, people will have a hard time accepting one idea in particular—the claim that Jesus could feel shame. Even as I write that sentence, I know some readers will immediately tune out anything else he says. Yet, I’m just as certain that no one who just read that sentence will actually grasp what Ten Elshof means.

The difficulty is not that Ten Elshof uses the word “shame” in an odd, unprecedented way. Rather, he reminds us of a basic idea underlying all definitions of shame.

This post explains what Ten Elshof means by “shame.” In the next post, I will clarify how it relates to various types of shame.

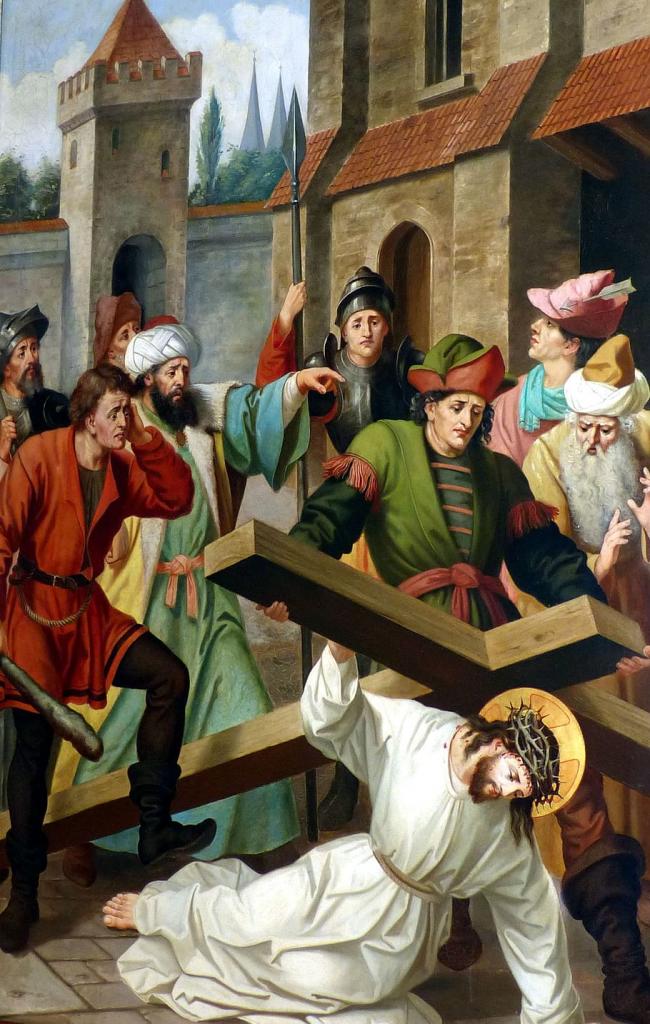

Jesus Experienced Shame

When people define shame, they usually link it to a loss of self-esteem. This popular understanding refers to psychological shame, the kind Brene Brown speaks about. But Ten Elshof says this:

“It is possible, after all, to experience shame (even quite intense shame) without any corresponding loss of self-esteem.

Recall, for example, the shame Jesus Christ suffered on our behalf. Jesus was publicly and falsely accused of something shameful and criminal—claiming to be divine while not divine. As a consequence, he suffered public ridicule and was widely shunned. He was publicly and disgracefully stripped of his clothing, tortured, and killed.

To put it mildly, he suffered a precipitous loss of social capital and connection. He was shamed. And according to Christian teaching, if it did not pain him to experience this loss of social capital and connection in company that mattered to him—if he did not undergo felt shame—he was not in all manner of things like us. Presumably, then, Jesus experienced felt shame—intense shame.

But just as clearly, he did not suffer a lowering of self-esteem. He did not judge himself to be a person of less worth, dignity, or ability as a result of his experience, and he did not experience any loathing affect directed at himself. His shame was great, but his sense of his own dignity and self-worth were unassailed.” (p. 62)

One could easily misread this statement. A reader could miss the nuance in his argument. We must be conscious of the fact that shame is multifaceted.

As I’ve said several times, people tend to talk past one another because they are generally familiar with certain aspects of shame. Writers from disparate fields use the same word but seem to talk about different subjects entirely. Consequently, we end up talking past one another.

(This is precisely why I wrote “Have Theologians No Sense of Shame? How the Bible Reconciles Objective and Subjective Shame.” In that article, I distinguish psychological, social, and sacred shame and note their presence in the Bible.)

But How Did He Experience Shame?

At first, Ten Elshof seems merely to highlight the social shame Jesus experienced, i.e., the community around him treated and regarded him as worthy of shame. But Ten Elshof implies more than that. He suggests that something is actually going on inside of Jesus.

He explains,

“Can shame be experienced apart from lowered self-esteem for us who are mere mortals?” It certainly can.

Imagine being publicly (though mistakenly) accused of an extremely shameful and criminal act. Imagine that the evidence publicly presented, though misleading, is compelling and damning indeed. And imagine that, as a consequence, you are widely shunned and poorly regarded.

You would lose social capital and connection and would suffer shame in the communities that matter to you. And if your emotions were tracking the situation in a healthy way, you would feel the pain of lost social capital and connection. But your opinion of yourself would not be affected.

Knowing you are innocent, you’d not think yourself less worthy, dignified, or able than prior to the accusation. You would suffer intense shame and have the painful emotional experience of yourself as an object of diminished social consequence in company that mattered to you. You would experience yourself as a source of discomfort and pain in the world. But you’d not necessarily sink into self-loathing or experience diminished self-esteem—at least not if shame is functioning as it should in your psychology.” (p. 63)

In focusing on the experience of Jesus, Ten Elshof underlines an aspect of shame that is implicit in other forms of shame. In short, shame entails a person’s sensitivity to the opinion of others.

Sensitivity to Opinion?

“Sensitivity” does not require agreement nor unhealthy neediness. Instead, it concerns both awareness and the displeasure that comes along with lost social connection. If a person does not have such sensitivity, they are called “shameless.” And, ironically, a shameless person is shameful.

As I and others have explained (like here, here, and here), shame is a moral emotion. A sensitivity for the opinion of another foundational for character development. Concern for other people’s opinions is inherent and thus necessary for cultivating humility.[1] Mencius says,

“Whoever has no sense of shame is not human.”[2]

Accordingly, the one who is not sensitive to shame is a threat to others.

While For Shame touches on several features of shame, this particular one often goes unnoticed or perhaps assumed.

In the next post, I’ll illustrate how shame-as-sensitivity-to-social-opinion relates to the other types of shame.

[1] Van Norden, “The Emotion of Shame,” 62.

[2] B. J. Yang, Mengzi yizhu [Translated notes on Mencius] (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 1960), 80.