Pilgrimage and Convocation

by John Beckett

Denton Unitarian Universalist Fellowship

August 17, 2014

My Introduction to Travel

When I was growing up, my family was blue collar middle class. We had everything we needed and not a lot more. Travel meant piling in an un-air-conditioned car with my parents and my pesky little brother and driving for hours on end to visit relatives. When we got there, my parents sat around and talked while I was left to fend for myself in a basement or a back yard. This did not instill an appreciation for travel in me.

When I got out on my own I told myself I couldn’t afford to travel. I was envious of my friends who went to Europe or on Caribbean cruises, and to be honest, those kinds of trips really were beyond my means. Other trips would have been affordable, but I didn’t see the value in them.

In 1993 I was pushed into a trip to New Orleans that was magical in many ways. That trip is another story for another time, but it showed me what travel could be. Since then, Cathy and I have taken a big trip every year except one, and over the past few years we’ve added a smaller trip at the Winter holidays in lieu of buying presents for each other.

Travel is relatively easy today – you can drive from San Antonio to El Paso in under eight hours. In the early days of Texas, it could take six weeks. The situation was similar in most parts of the world. But despite the costs, difficulties, and dangers of travel, there has always been one reason ordinary people as well as the rich and powerful have undertaken long journeys – religious pilgrimages.

Pilgrimage

For almost 2000 years, Greeks from all over the Mediterranean traveled to Eleusis for initiation in the Mysteries. Jews traveled to Jerusalem to offer sacrifices at the Temple prior to its destruction by the Romans in 70 CE. A pilgrimage to Mecca is one of the Five Pillars of Islam. Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales is set on a pilgrimage to the shrine of St. Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral. There are countless other examples.

The Catholic Encyclopedia says pilgrimages are “journeys made to some place with the purpose of venerating it, or in order to ask there for supernatural aid, or to discharge some religious obligation.” I think that definition is a good start.

There is value in religious tourism – going to some place of religious significance simply to see it. My visit to Westminster Abbey in 2007 was quite informative and even inspirational, but it was not a pilgrimage. Neither was my visit to Stonehenge, which as a Pagan I found more meaningful. My visit to the massive stone circle in Avebury, though – that was quite a pilgrimage. So was my visit to the Isle of Anglesey in Wales earlier this year.

So what is a pilgrimage, and what differentiates it from ordinary travel? A pilgrimage begins with a religious intent. There’s something special about the destination. Pagans like to say “all land is sacred” and the poet Wendell Berry said “there is no unsacred place.” But some places are especially sacred – they’re places of natural power, or places made sacred by important human activities. The pilgrim expects that there will be something special, something extraordinary, something sacred at her destination. There will be something there she can’t find at home, whether that is healing at Lourdes, prayers at the Wailing Wall, bathing in the Ganges, or the return of the light at Newgrange.

These expectations create anticipation. Now, we all know the disappointment that follows unrealistic expectations, but an open-ended hope for a good experience prepares the pilgrim for what will come. And the anticipation provides motivation to do the work that will be required to complete the pilgrimage.

A pilgrimage involves a journey, and the journey can be as important as the visit. Even with planes, trains, and automobiles, the travel will still take longer than the visit to any one site. And while travel is far easier than it once was, it still brings frustrations and hardships. Overcoming them makes reaching the destination all the more meaningful.

What do you do when you get there? You’re not there just to see the sights – you’re there to do something. You may participate in a ritual, either individually or with other pilgrims. On those few occasions when my family was traveling on a Sunday, my parents would always find a church for us to attend. I wanted a vacation from church too! But when Cathy and I visited Boston last year, we attended Sunday services at First Parish, Cambridge, a UU church founded in 1633. The service itself would not have been out of place here in Denton. What made it special was worshipping where others have worshipped for almost 400 years.

I have a Catholic friend whose trip to Rome was highlighted by attending mass in St. Peter’s Square. It was an ordinary mass, but it was in a special place, with thousands of others who share her faith, and of course, with a special officiant.

Sometimes the experience you expect isn’t the experience you get. As a modern Druid, I had great expectations for our visit to Anglesey earlier this year. Anglesey was a center of Druid learning in ancient times, and it was the site of the infamous Roman massacre of 61 CE. From the beginning, I had planned to slip away for a few minutes on our last morning there and commune with the spirits of the place. I was hoping for a connection to the ancient Druids and perhaps a vision of a past life. There was a stone circle in what was essentially the back yard of our hotel. It’s a modern circle built for bardic gatherings, but it’s still a stone circle on the Isle of Anglesey – it was clear that was where I was supposed to do my communion with the place.

In a light, cold rain, I approached the circle and poured a libation at the entrance. I walked the circle clockwise and then moved to the center stone. What I experienced wasn’t a past life memory or really any connection to the past. Rather, it was an offer and a challenge to step up, both literally and figuratively, and to embody the spirit of that great place in my daily life back here.

This was not the experience I was expecting. This was not comfort and healing. It was inspiring, but in a “get your butt in gear” way, not with any visions of wisdom and peace being dispensed from on high.

What do you say to an experience that is not what you expected and perhaps not what you wanted? What do you say to an experience that challenges rather than comforts? If your trip was a pilgrimage and not tourism, if it was driven by a religious impulse, you say yes.

When your experience is over, your pilgrimage is not done – you’ve still got the return trip. And as with the journey to the pilgrimage site, the journey home can bring its own challenges and its own rewards. Mostly, though, the trip home gives you time to process the experience. What does it mean? What did you learn? And perhaps most importantly, how are you going to incorporate it into your life?

Convocation

There is another form of religiously motivated travel – convocation. The word simply means a large formal assembly – a retreat or a workshop or a business meeting. The UUA has its annual General Assembly, and our regions and districts have various camps, educational events, and other opportunities to gather in an environment that is distinctly Unitarian Universalist.

Each September for the last three years I’ve travelled to eastern Pennsylvania for the East Coast Gathering of the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids. About a hundred Druids from all over the country and a few from elsewhere gather for a four day weekend at what is normally a girls’ summer camp. There are rituals and workshops, guest speakers, and evenings around the camp fire singing, telling stories, and drinking mead. It’s a beautiful site and I’d enjoy getting away for a few days no matter what the excuse. But the reason I keep going back year after year is the opportunity to immerse myself in Druidry for four days straight.

There are conversations that take place at the East Coast Gathering that some of our members simply can’t have any other place. People can let their guard down and share their spiritual journeys, talk about their projects and their ideas, their hopes and fears for the future. They discuss the nature of the gods and what comes after death, and their thoughts are as diverse as any group of UUs. These are the kind of conversations many of us are reluctant to have in the ordinary world for fear of being seen as odd or nuts or worse.

Social media has made it easier to connect with friends from around the world, but there is no substitute for seeing someone face to face and having a real, live conversation over a cup of tea.

Some convocations are retreats and some are workshops, but some are working business meetings. Our General Assembly has its plenary sessions where various reports and motions are considered, debated, and voted on. This may sound boring compared to the inspirational religious experiences of pilgrimages and the soul-nurturing fellowship of retreats, and many times it is. That doesn’t mean it’s not important.

In 325 CE the Roman Emperor Constantine sent out a call for all Christian bishops to participate in a council to settle various disagreements within the still-new Christian church – the nature of the relationship between the Father and the Son and the date of Easter being the most prominent. 1800 bishops were invited to participate in the council. 300 showed up. Those 300 bishops made decisions that are still in effect today. What would the Council of Nicaea have been like if the other 1500 bishops attended?

The standard Christian position is that the Council was guided by the Holy Spirit and thus would have reached the same conclusions no matter who was involved. Perhaps. Others say those 300 bishops were a representative sample of Christian thought at the time and thus reached the same conclusions as if Constantine had polled all of Christendom. Perhaps. Still others argue that those who made the long and difficult journey to Nicaea (in what is now northern Turkey) were the most invested and most passionate and therefore would have carried the argument no matter who attended. Perhaps.

The Council of Nicaea decided key matters of theology and issued a creed that is still in use by Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox Christians after almost 1700 years. What would the Nicene Creed be if more than 300 bishops had participated? We’ll never know. Here’s what we do know: major decisions were made by those who showed up.

Whether it’s a religious convocation, a congregational meeting, or a political debate, ultimately someone has to decide. If you choose to participate, the decision may go for you or it may go against you. If you choose not to participate, the decision will be made without you. Decisions are made by those who show up.

Travel Now

If there’s a pilgrimage that calls to you, I have one suggestion – do it now. If you have issues that simply do not allow you to travel, then plan for the time when you can. But otherwise, go now. You never know when a particular pilgrimage will no longer be possible.

I have wanted to visit Egypt for as long as I can remember. First it was The Ten Commandments and The Mummy movies. Now it’s my religious work with the deities of ancient Egypt. I’ve seen bits and pieces of Egypt in the touring exhibits that came to museums in Fort Worth and Dallas. I’ve seen other artifacts in London and Istanbul. Those have been meaningful and even powerful. But I want to see the Pyramids, the Sphinx, and the Nile for myself. I want to stand in the ancient temples and whisper prayers to Isis, Osiris, and Amun Ra.

But a trip to Egypt has always been one of those things I planned to do “some day.” It’s always been too expensive, too difficult, and now, too dangerous. I’m hoping to go to Egypt in 2016, or if the political situation is still unsettled, in 2018. But “some day” has an expiration date, a date that is closer for some destinations than for others.

I’m now well into my 50s, and accommodations I once saw as luxuries I now see as necessities. Not because my tastes have changed, but because my body has changed. I used to could sleep anywhere – now a night in a bad bed may have my back in pain for days. I can still spend all day walking around a city or countryside, but if I do I’ll need a rest day tomorrow. Keep in mind that many sites of religious significance and natural beauty are in hard-to-reach locations. I could go back to Stonehenge when I’m 90, but I don’t know that I want to be hiking or even bussing through the Egyptian desert if I’m going to be more concerned with my physical condition than with the places I’m visiting.

Pilgrimages are not vacations and challenges are to be expected. Your body, your threshold of discomfort and your tolerance of risk will vary. But for all of us, there will come a day when travel is no longer possible.

If you want to see the glaciers of Alaska, go now – they’re melting. If you want to see the jungles of the Amazon, go now – they’re being developed at an alarming rate. Neither are likely to disappear in the immediate future, but they are changing rapidly. If you want to see the Buddhas of Bamiyan, you can’t – the Taliban blew them up in 2001. If a pilgrimage calls to you, go before “some day” becomes “I wish I had.”

Pilgrimage Ideas

Pilgrimages are very personal things. A journey that is extremely meaningful to me may not interest you at all, and vice versa. But there are some destinations that will be of interest to many UUs, and not all of them involve long and expensive travel.

For Unitarian Universalists, there is no better place for a pilgrimage than Boston. You can visit UUA headquarters, but that always struck me as a working office and not a sacred site. But do visit King’s Chapel. It was founded in 1686 and the current building was opened in 1754. It’s a Unitarian Christian church using a modified Anglican liturgy, and it is a member of the UUA. Visit First Parish in Cambridge. It was founded in 1633 and the current building was opened in 1833.

Drive out to Walden, see the statue of Henry David Thoreau and the replica of his famous cabin. Walk around Walden Pond – you don’t have to think very hard to understand why Thoreau chose this site for his two year experiment in simplicity.

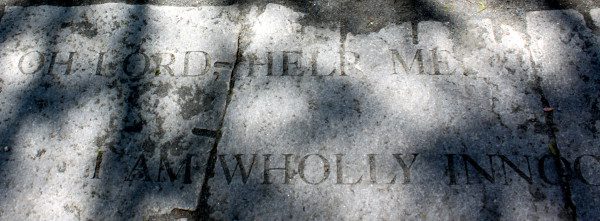

Take a side trip to Salem, which is closer to Boston than Denton is to Dallas. Salem is a tourist town that milks the witch theme for all it’s worth – set your expectations accordingly. But pay a visit to the Witch Trials Memorial. Read the pleas of the condemned engraved on the stones, and remember that even today people are killed for things they did not do.

About six hours east of here is Poverty Point. This was home to the mound building people who lived here 3500 years ago. At first glance it’s unimpressive: a series of low ridges that could be overlooked if not for the mowing patterns, and a couple of earth mounds that are out of place on the flat land but not so obvious as to scream “monument!”

About six hours east of here is Poverty Point. This was home to the mound building people who lived here 3500 years ago. At first glance it’s unimpressive: a series of low ridges that could be overlooked if not for the mowing patterns, and a couple of earth mounds that are out of place on the flat land but not so obvious as to scream “monument!”

But between 1600 and 1100 BCE, hundreds of people lived here, part of a culture that stretched for hundreds of miles up and down the Mississippi River. They had no earthmoving equipment, no pack animals and no wheeled carts. They had only baskets and people – the mounds would have taken years to build. Why did they make the investment of time and effort?

Go to Poverty Point. Climb the stairs to the top of the largest mound. Look around at the surrounding countryside. Let your focus shift and try to imagine what you would have seen if you had been there over 3000 years ago. Think about how the people lived. What did they know that we’ve forgotten?

Less than two hours south of here is Dinosaur Valley State Park. 110 million years ago this area was the shoreline of a shallow sea and home to several species of dinosaurs. They left their footprints in the lime-based mud and the prints were quickly covered with a layer of clay, preserving them for eons. In 1908 the footprints were uncovered by a flood and they’re visible today in the Paluxy River, especially in times of drought when the river is running low and clear.

Go to Dinosaur Valley. Stand in the footprints of the huge dinosaurs. Listen. Contemplate just how old the Earth really is, and just how new we humans really are. Think about the dinosaurs and how their world changed so suddenly and so drastically. You can do that anywhere, but there’s something special about doing it where there is such a tangible connection to creatures who lived so long ago.

The Wider Cost of Travel

Travel is easier and more affordable than it’s ever been, but travel still has costs, including environmental costs. All forms of transportation produce greenhouse gasses and air travel is especially dirty. You may wish to offset the pollution of your trip by planting trees or by cutting back on fossil fuel use in other areas of your life.

There are some places we are loving to death – they are being harmed by the sheer volume of people visiting them. High entrance fees and timed tickets are not simply designed to manage large crowds, they’re also designed to reduce them. The caves of Lascaux and their famous Paleolithic paintings have been closed since 1963. The humidity and carbon dioxide produced by human visitors would have destroyed in a few decades what had been preserved for 15,000 years.

Pilgrimages aren’t logical things. We’re moved to go places we’ve never seen by forces we don’t understand to have experiences we can’t explain. The call to pilgrimage wants what it wants. But to the extent you have a choice in how to respond to your call, I encourage you to consider lesser-known sites. They’re typically not as big and not as visually impressive, and they can be harder to reach. But these places can be just as powerful as the better-known sites, and they typically have far fewer visitors. I’m sure my Catholic friend had a memorable experience of mass with thousands of others in St. Peter’s Square. But I’ll never forget visiting Anglesey with a party of six, and standing in the center of that circle, alone, and not.