Sparks flew last week when the March 2019 edition of Esquire was released. “An American Boy,” the headline on the cover reads. “What it’s like to grow up white, middle class, and male in the era of social media, school shootings, toxic masculinity, #MeToo, and a divided country,” the byline adds. The cover features an image of a white teenage boy sitting on a bed putting on his sneakers, staring into the camera.

The article itself is uninspiring. The article’s subject doesn’t have that much to say. He’s not terribly politically interested. He’s no David Hogg. Maybe that was the point, but it doesn’t make for particularly interesting reading. This is a story we know—a white boy in the Midwest who likes to hunt, hang out with his girlfriend, and play video games.

My issue here is with the framing.

While the cover’s byline makes it clear that the article is only ever intended to be about white boys, the headline does not make this distinction. “An American Boy,” it declares. One wonders. Would Esquire have given the same title to a profile of a black teen, or a Hispanic teen? This article, after all, isn’t really about what it’s like to be an American boy. It’s about what it’s like to be a particular type of American boy—a white, semi-rural Midwestern one.

Whiteness is frequently treated as some sort of default. I’m reminded of the American Girl dolls I grew up with. Each doll was placed in a different historical period. The only black doll was an escaped slave set during the Civil War. The Revolutionary War doll was white; the pioneer doll was white; the Victorian era doll was white; the Depression era doll was white; the WWII doll was white. To be an American girl was to be white—unless one lived in a brief historical moment when being non-white was part of the story. (This is also why black people disappear from U.S. history textbooks between Reconstruction and the rise of the civil rights movement in the late 1950s.)

(I am not forgetting Josefina. Pleasant Company did do some things well. Josefina familiarized a generation of girls with long history of Hispanic peoples living within what are now the boundaries of the United States—and opened their eyes to the fact that portions of the United States were once part of Mexico. I am also not anti-Addy. I am simply making a point that all the generic historical moments got white dolls. Because generic American girls are white.)

The generic American boy is white. Of course he is. As with American Girl dolls, white is treated as the default. An American boy is by default white. But is he really?

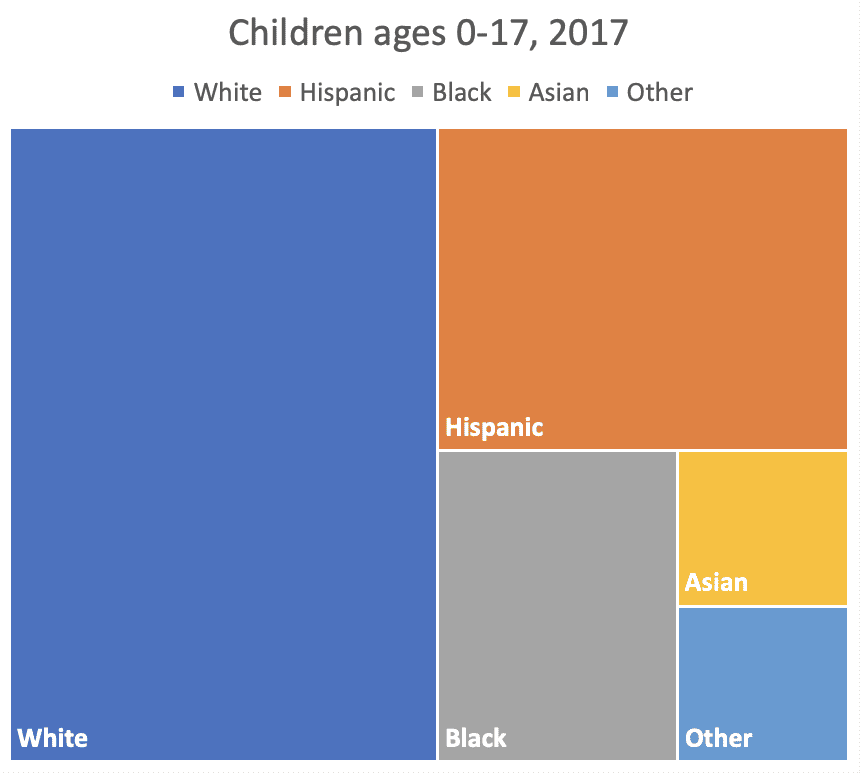

Fewer than 50% of children born in the U.S. today are white. As of 2017, 51% of children overall were white, while 49% of children under 5 were white.

Since its founding, the United States has always been made up of different peoples. A hundred years ago, Anglo-Saxon Protestants were treated as the default; Catholic immigrants and immigrants from eastern and southern Europe were othered and viewed as less than American. Today, these groups have attained whiteness. This is not the case, however, for African Americans, Hispanic Americans, and Asian Americans. As a result, the new default is a generic whiteness.

The black teen living in Milwaukee is just as much an American boy as the white suburban subject of Esquire’s story. So, too, is the Hispanic teen living in Chicago; the Hmong teen living in Minneapolis; and the Native American boy living in Menominee. An article following the lives of these five teenage boys would have given us a far more rounded picture of the life of an American boy in our composite nation, without even broadening the geographic scope.

Of course, the framing issue I’m having could also have been fixed by changing the article’s title. This story was never about the life of teenage boys in America, and it wasn’t intended as such. It was always about the life of a specific type of white, middle class American boy. “Growing Up White and Male in Middle America” would have been a far more accurate title. Or perhaps, shorter and more in the tone of the article, “Age of Confusion.”

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!