As I read about the Saturday’s mass shootings—at least one committed by a white supremacist—I came upon an article that began with this image:

Trump stands at a microphone, facing the camera, in mid sentence. Just above him and in nearly the same proportions is painting of the United States’ first president, George Washington. The two presidents fill the picture, framed by white, empty wall on each side. The counterposition is striking.

We often think of Trump as some sort of presidential aberration. But is he really? Or is he perhaps made more in the mold of earlier presidents than we would like to think? Certainly, there are some exceptions—Abraham Lincoln, Barack Obama—but in general, U.S. presidents have rarely shirked from openly promoting white supremacy, from Andrew Jackson to Richard Nixon to Ronald Reagan.

George Washington owned slaves, but our history books are quick to tell us that he freed them in his will. The period from 1780 to 1800 was a rising number of slave manumissions in the upper south, driven in part by moral qualms about slavery rising from the rhetoric of the American Revolution. In Virginia, the proportion of free blacks rose dramatically during these years. This brief period ended in 1800, when the doors of manumission slammed shut and proslavery sentiment surged.

We are told that the American Revolution, with its rhetoric of liberty, affected Washington’s view of slavery. We are left to assume that he become a reluctant slaveholder, retaining his slaves only to maintain his position, intent on freeing them on his death. This position—to delay putting an end to human chattel slavery in order to maintain one’s social status for a few more years—would have itself been reprehensible. But the story of Ona Judge severely complicates even this narrative.

Ona Judge, a slave of George and Martha Washington, liberated herself in 1796, while George Washington was president of the United States, and less than four years before his death.

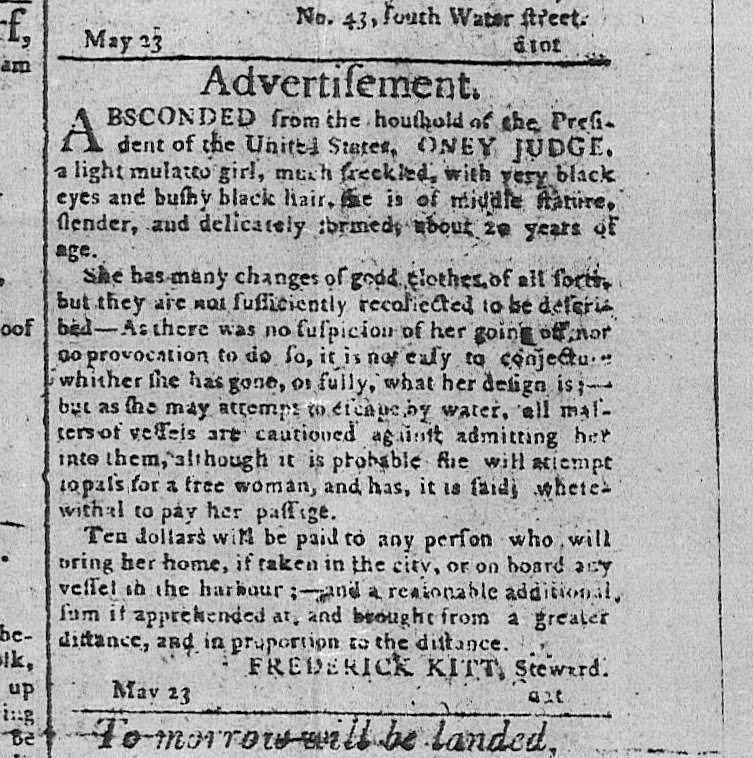

Like many other slaveholders seeking to locate slaves who had liberated themselves by running away, George Washington took out an advertisement offering a reward for her return. Its text ran as follows:

ABSCONDED from the household of the President of the United States, ONEY JUDGE, a light mulatto girl, much freckled, with very black eyes and bushy black hair, she is of middle stature, slender, and delicately formed about 20 years of age.

She has many changes of good clothes of all sorts, but they are not sufficiently recollected to be described—As there was no suspicion of her going off, nor no provocation to do so, it is not easy to conjecture whither she has gone, or fully, what her design is—but as she may attempt to escape by water, all masters of vessels are cautioned against admitting her into them, although it is probably she will attempt to pass for a free woman, and has, it is said, wherewithal to pay her passage.

Ten dollars will be paid to any person who will bring her home, if taken in the city, or on board any vessel in the harbour;—and a reasonable additional sum if apprehended and brought from a greater distance, and in proportion to that distance.

Ona had numerous changes of clothes because she was Martha Washington personal maid. In 1796, the Washingtons lived in Philadelphia, which was then the capitol, rather than at their Mount Vernon estate in Virginia. Bec cause of Ona’s position as Martha’s personal maid, Ona lived in Philadelphia.

In Pennsylvania, slavery was governed by the Gradual Abolition Act of 1780. According to this act, if a nonresident slaveholder brought slaves into Pennsylvania and kept them there for six months or more, those slaves would become free. An amendment in 1788 prohibited nonresident slaveholders from rotating their slaves out of the state inside of this deadline to prevent their obtaining freedom.

George Washington rotated his slaves out of the state inside of the six month deadline to prevent their obtaining freedom, in direct violation of Pennsylvania law, and no one stopped him, presumably because he was the president. Ona was one of these slaves. Every six months, she was taken out of the state of Pennsylvania, and then back in, so that her residency period would begin over again.

By rights, Ona should have been free. Washington did not give a damn. He broke the law and engaged in deliberate subterfuge to keep her enslaved. Ona ran away after learning that she was going to be gifted to Martha Washington’s granddaughter, and shipped south, likely never to return. She had made friends among the free black population of Philadelphia, and they helped her escape.

Washington’s willingness to flagrantly violate Pennsylvania state law to prevent his personal slaves from gaining freedom suggests that he was more than a reluctant slaveholder.

After some months, Washington received a report that Ona had been sighted in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Activating the machinery of the federal government, he reached out to Oliver Wolcott, the Secretary of the Treasury, who then contacted Joseph Whipple, the U.S. Customs Collections officer in Portsmouth, directing Whipple to find Ona and return her to Washington.

Whipple was told that Ona had been abducted from the Washingtons by a suave Frenchmen who had seduced her. When Whipple made contact with Ona—luring her into his office with the promise of employment—he queried whether perhaps she had a French boyfriend. Ona was aghast. She told Whipple that she had run away because she wanted to taste true liberty, and for no other reason.

Not one to be put off, Whipple asked Ona if she would go back if Washington promised to free her later. Ona said she would, and they parted ways. But when Whipple contacted Washington, Washington told him that he would under no circumstances make any promise to free Ona. His response included a veiled threat against Ona’s family, still enslaved.

Ona blew Whipple off, and evaded capture. Two years later, after Ona had married a free black man and given birth to an infant daughter, Washington sent his nephew to kidnap her and the child, who was also legally considered Washington’s property. Ona received warning in time, and went into hiding along with her infant. Ona spent her entire life a fugitive, but successfully evaded recapture.

Fifty years after she liberated herself, Ona was interviewed by an abolitionist:

Being a waiting maid of Mrs. Washington, she was not exposed to any peculiar hardships. If asked why she did not remain in his service, she gives two reasons, first, that she wanted to be free; secondly that she understood that after the decease of her master and mistress, she was to become the property of a grand-daughter of theirs, by name of Custis, and that she was determined never to be her slave.

This statement echoes what Ona told Whipple, the customs collector who attempted to retrieve her for the Washingtons. On October 4, 1796, Whipple wrote the following to Oliver Wolcott, the Secretary of the Treasury, who had originally contacted him at Washington’s behest:

Having discovered her place of residence, I … caused her to be sent for as if to be employed in my family. After a cautious examination it appeared to me that she had not been decoyed away as had been apprehended, but that a thirst for compleat freedom which she was informed would take place on her arrival … had been her only motive for absconding.

Like I noted, Whipple had been told that Ona was lured away by a conniving Frenchman. Also, he lured her into his office under the pretense of offering her employment. That is godawful. But note what Ona told Whipple: she ran away because she had a thirst for complete freedom.

Whipple goes on:

It gave me much satisfaction to find that when uninfluenced by fear she expressed great affection & reverence for her Master & Mistress, and without hesitation declared her willingness to return & to serve with fidelity during the lives of the President & his Lady if she could be freed on their decease, should she outlive them; but that she should rather suffer death than return to Slavery & [be] liable to be sold or given to any other persons.

Whipple claims that the vessel he booked Ona’s passage back to Washington on was delayed, and that in the meantime some of Ona’s “acquaintances” found out her intention to return, and persuaded her against it. I’m skeptical of his assumption that she told him the truth about her willingness to return.

This said, Ona’s statement about being sold or given to other persons rings true. Ona ran away, she stated fifty years later, because she had learned she was to be given as a gift to Martha Washington’s granddaughter. She likely knew that that forestalled any chance that she might be freed on the Washington’s deaths. Ona was in her early twenties and had her whole life before her.

Washington replied directly to Whipple:

I regret that the attempt you made to restore the Girl (Oney Judge as she called herself while with us, and who, without the least provocation absconded from her Mistress) should have been attended with so little Success.

No provocation? Seriously? Slavery is a provocation.

To enter into such a compromise with her [i.e. guaranteeing her future freedom], as she suggested to you, is totally inadmissable, for reasons that must strike at first view: for however well disposed I might be to a gradual abolition, or even to an entire emancipation of that description of People (if the latter was in itself practicable at this moment) it would neither be politic or just to reward unfaithfulness with a premature preference; and thereby discontent before hand the minds of all her fellow-servants who by their steady attachments are far more deserving than herself of favor.

Oh god, I hate him already. What does one have to do to be deserving of freedom? Washington suggests that he is “well disposed” to “gradual abolition” but the way he talks about his enslaved people suggests that he sees it as something they have to earn, and be deserving of. I am not sure I like this viewpoint any better than that of those who opposed abolition altogether.

Washington goes on:

I was apprehensive (and so informed Mr. Wolcott) that if she had any previous notice more than could be avoided of an attempt to send her back, that she would contrive to elude it; for whatever she may have asserted to the contrary, there is no doubt in this family of her being seduced, and enticed off by a Frenchman, who was either really, or pretendedly deranged, and under that guise, used to frequent the family; and has never been seen here since [the] girl decamped. We have indeed, lately been informed thro’ other channels that she went to Portsmouth with a Frenchman, who getting tired of her, as is presumed, left her; and that she had betaken herself to the needle, the use of which she well understood, for a livelihood.

There was no Frenchman.

Washington cannot bring himself to consider that Ona honestly wanted to be free. He cannot fathom why any slave would willingly run away from him. What a horrible human being.

And then we get this mess:

If she will return to her former service without obliging me to use compulsory means to effect it her late conduct will be forgiven by her Mistress, and she will meet with the same treatment from me that all the rest of her family (which is a very numerous one) shall receive. If she will not you would oblige me, by resorting to such measures as are proper to put her on board a Vessel bound either to Alexandria or the Federal City. …

I do not mean however, by this request, that such violent measures should be used as would excite a mob or riot, which might be the case if she has adherents, or even uneasy Sensations in the Minds of well disposed Citizens; rather than either of these should happen I would forego her Services altogether, and the example also which is of infinite more importance. The less is said beforehand, and the more celereity is used in the act of shipping her when an opportunity presents, the better chance Mrs. Washington who is desirous of receiving her again) will have to be gratified.

Good god. Surely he has to know that what he is asking Whipple to do is wrong. He’s aware that trying to recapture Ona could result in a riot or a mob, but he shows no interest in understanding why.

All that’s important is that Martha wants Ona back.

And then we get this:

We had vastly rather she should be sent to Virginia than brought to this place [Philadelphia], as our stay here will be but short [Washington’s second term was nearing its end]; and as it is not unlikely that she may, from the circumstances I have mentioned, be in a state of pregnancy.

George Washington

Pregnant! Ona, pregnant by the Frenchman?!

Ona was not pregnant by a Frenchman. There was no Frenchman. Ona engineered her freedom on her own, receiving help from free black friends in Philadelphia.

Washington’s efforts to capture Ona sound, dare I say it, Trumpian. First of all, Washington used a loophole in the law to maintain his “property” in direct violation of what the law intended. Trump has done this sort of thing lots of times. Next, he spun stories about Ona and her motivations that were complete fabrications. Who else is good at lying through his teeth? And finally, the horribly patronizing discussion of who “deserves” freedom sounds sadly familiar.

None of this is to suggest more than I have directly stated. I understand why people (myself included) so often treat Trump as an aberration—there certainly are differences. But in some sense, what makes him feel most different from many other presidents may be his willingness to state openly what other presidents have typically stated more privately. The white supremacy present in Trump’s words is not an aberration, either for the United States in general or for the U.S. Presidency.

Yes, our nation’s founding documents are graced with seemingly inclusive rhetoric. That rhetoric is important: for over two hundred years, rights movements have latched onto our founding documents’ seemingly inclusive rhetoric to assert their humanity and to argue for their own inclusion in the project that is the United States. But that rhetoric was also fundamentally hollow.

It can be uplifting to see our nation’s history as one characterized by a string of civil rights pioneers who have gradually and over time expanded the range of groups included in our national project. But it is important to remember that our nation’s history includes not only those pushing for rights for more groups but also those these individuals had to push against. Our nation’s history includes Ona Judge, whose courage and persistence inspires—but it also includes George Washington.

Maybe that is why I found the photo at the top of this post so striking—because it reminded me so strongly, so viscerally, that Trump is not an aberration, but a continuation of a long tradition of lies, of white supremacy and repression of people of color, of willingness to trample others to get to the top, of legal fraud designed to maximize individual property wealth at any expense.

Trump is terrifying not because he is different, but because he has forced us to stare in the face of a part of the American tradition that we had hoped to forget about, and in so doing erase.

Somehow, erasing never works quite like that.

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!