If you’re anything like me, you’ve been following the U.N. Climate Summit, and especially the sixteen children who are suing five countries under the U.N. Convention on the Rights of the Child (which the U.S. has not signed, by the way), for violating their rights by not taking action on climate change.

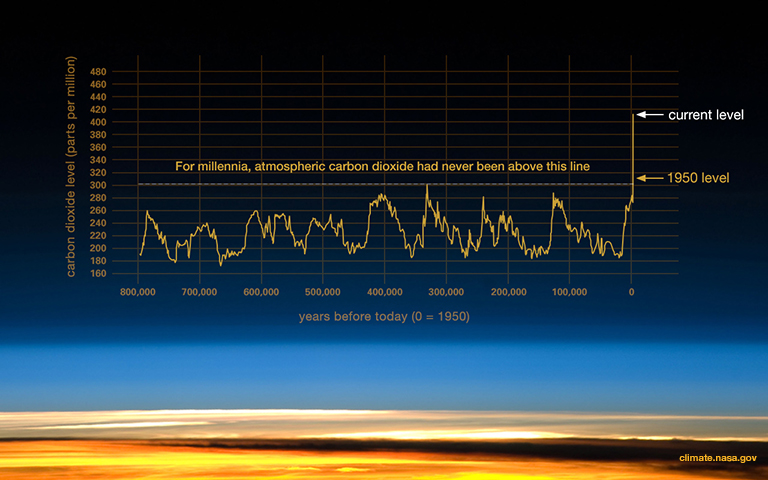

I knew that the level of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere has varied over the past million years of the earth’s history, rising during interglacial periods and falling during ice ages. But did you know that the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is now as much higher than the highest interglacial period as that period’s level was higher than the level of the lowest ice age?

“I think the next president is going to do something about climate change,” my youngest child told me a few days ago. “Why do you think that?” I asked. “Because I keep hearing them talk about climate change on NPR and stuff,” he told me. “So I think the next president is going to do something. My older child, not yet in middle school, responded by telling him that when she’s in charge, she’s going to give everyone in the whole country an electric car to replace the gasoline powered cars they own now.

I didn’t have the heart to tell her that by the time she’s in charge, it’s going to be too late. That’s why Greta Thunberg and her fellow youth activists have grown so upset. They’re old enough to know that by the time they’re in charge, it’ll be too late. Sometimes I feel guilty for bringing children into the world. They get to live their entire lives dealing with the ricocheting consequences of the mess we’ve created.

At moments like these, I feel a desperate desire to help. To do something. This is often accompanied by a feeling of overwhelming helplessness. There’s not a lot more I can do in the most obvious areas. I live in a city. My husband and I either commute to work using public transit, or work from home. My kids walk to school and bike to music lessons. We have one very small car that we use only a few times a week, for groceries and such. Our electricity is provided by a nuclear power plant.

But we still take vacations. Our tiny car may get amazing gas milage, but it does still run on gas. And we occasionally fly. Every fall, we drive an hour and a half out of the city to an apple orchard, so that the kids can spend the day picking apples and getting lost in a corn maze. Is it worth it? I’d like to take my children on a road trip to the Grand Canyon. I’d even like to go backpacking in Europe with them someday. All of those things mean more carbon dioxide.

You can’t get to any national park using mass transportation. Or can you? Perhaps I should start googling Amtrak. But then I wonder, can I live my whole life like this, scrutinizing my every decision?

The moments I feel helpless underscore the extent to which we are all stuck. Last night, my husband picked up dish soap at the local drugstore. We’d been almost out. When he put it on the counter, I stared at it, dispirited. We had brought another plastic bottle into the world. I went online and tried to look up health food stores where I could refill the dish soap. I tried to calculate how far I’d be willing to drive, and then I remembered that driving meant carbon dioxide. How far would be worth it?

I gave up.

Many other Americans are as stuck in their commutes as I am in my dish soap purchases. Not everywhere has public transit. In fact, most places don’t. Our country was built on cheap fossil fuels, and as such, it is structured around them.

This morning, I put bread on the griddle to prepare grilled cheese for my children’s lunchboxes, like every morning. I pulled a slice from my box of Kraft singles, purchased at Sam’s Club, and felt sick to my stomach as I peeled the plastic from the cheese slice.

Over the summer, I bought a container of single-serving applesauces so that my kids would have easy snacks on hand. There’d been enough left that I’d been putting them in their school lunches. They loved it, but my regret grew every time I saw the plastic waste generated by every serving. Yes, we recycle. But what with all the talk of China no longer accepting the U.S.’s recycling waste, I don’t feel confident about where it goes.

When the single-serving applesauces ran out, I told the kids I wasn’t buying more. I reached into the fridge, figuring that I’d start putting string cheese in their lunches instead, only to pause, looking at the plastic wrapping as though I hadn’t seen it before.

Maybe I should start sending bananas. Those come in their own bio-wrappers, no need for any plastic! But wait. They’re shipped from South America, aren’t they? How much carbon dioxide does it shipping them mere create? Perhaps I should start sending hardboiled eggs. Those also have de-facto bio-wrappers, and the eggs we buy come in cardboard containers, not the styrofoam kind. Wait. Do chickens create carbon dioxide?

I feel like I’m drowning in single-use plastic, and in impossibly complex decisions.

I’d thought using paper bags at the grocery was better than plastic, because of how long plastic takes to break down. Then I read that it takes four times as much energy to create a paper bag as a plastic one—which means more carbon dioxide—and, of course, making paper bags involves cutting down trees. To add to that, paper bags put off carbon dioxide when they degrade.

I’ve started purchasing my fruit and vegetables at a local grocery store that sells them loose, using reusable mesh bags instead of the plastic ones provided in roles in the produce sections, which feels like a victory. I’ve also started reusing plastic ziploc bags, and have bought some reusable ziploc bags that are thicker, made to be used again and again. I’ve bought reusable grocery bags that fold up, making them easy to stick into any purse or backpack, so that I’ll always have one on hand. (Okay, usually.)

But then I read that it takes 131 times more energy to create a reusable cotton grocery bag than it does to make a regular plastic grocery bag. Am I actually going to use each of the reusable bags I bought 131 times? Will I even remember it that many times? I know I don’t have that much faith in myself. When it comes to carbon dioxide, at least, I was probably better off using the plastic bags at the counter.

I’m left wondering how many uses I have to get out of the thicker, reusable ziploc bags I bought to justify purchasing them, rather than just using the regular thin, single-use ziploc bags. Did I make a mistake?

Yesterday I found myself idly wondering whether it wouldn’t be better if we could go back to life before thee neolithic revolution, when people lived in simple dwellings made with things on hand, and found ways to make arts and crafts using needles shaped out of bones, and other natural products. How much simpler that sounds, with children playing with simple matched together dolls and carefully whittled hobby-horses, and not this conglomeration of masses of plastic toys and rampant consumerism.

Then I remembered that if I lived before the neolithic revolution—when life was simple and I wouldn’t have to worry about the environmental impact of every little decision—I’d be dead. Pesky little thing, appendicitis.

As I cycle through all of these thoughts, I worry about my children. Listening to my husband and I talk about climate change—rehashing things we’d read or heard on the news—brought my younger child nearly to tears last night. Is it fair to them, to grow up with this worry hanging over their heads? My husband spent some time talking to the poor child about efforts to curb climate change, about progress and successes and about things we’re doing to help, too.

There is the perennial discussion about our car, you see. Living in a city, we don’t need it for most things, but there are times when it would be nice to be able to transport more than five people. For example, that apple orchard trip? Last year my husband had a conflict, so I took the kids and two of their friends. They want to take their friends again this year, but my husband wants to go, too—and the car only fits five.

We are constantly transporting extra kids, and the limited seating car situation means we often have to get creative. Have you ever taken six kids to the movie theater via the train? I have. Have you ever walked four children to a diner almost two miles away, the morning after a sleepover? I have. Sometimes—just sometimes—it would be super handy to be able to transport extra kids in a car.

Every few months, my husband and I look up minivans and SUVs that fit 7-8 people. We always give up. You can’t get that seating without sacrificing gas milage, and I like getting 40 miles to a gallon. It’s not just about the money. It’s also about the carbon dioxide. I just can’t justify getting a bigger car. So I’ll go on putting six children on a train, and telling my kids to buck up and keep on walking.

At least I can usually distract them with geocaching.

Some fixes are probably going to need to happen at the corporate level. If I wanted to do all of my grocery shopping without buying any single use plastics, I’m not entirely sure what we’d eat. Even black beans and rice typically come in plastic bags. I stood at the grocery store a few days ago looking at a plastic container of hummus. What was better, I wondered: buying that container, or making hummus at home? Dried chickpeas come in plastic bags. I buy tahini in glass jars. This was clearly above my pay grade. What if the hummus company just decided to use cardboard with a thin plastic lining instead?

Of course, it’s actually a bit more complicated than that. Does it take more energy (and thus expend more carbon) to make a plastic container, or a cardboard one? Which has a larger carbon footprint? How the heck am I, the consumer, supposed to know the answer to that?

Perhaps the answer is a carbon tax. If companies paid a fine for the amount of carbon dioxide they produce, they would find ways to switch to packaging that puts off less carbon dioxide to produce. Now, we often pay extra for items we believe are more energy efficient, or better for the environment. What if it were the opposite? What if items that damaged the environment were the ones that cost more?

Of course, any such change would have to be accompanied by robust efforts to ensure that the weight of such measures did not fall disproportionately on the poor. I’m not at all confident in our country’s ability to pull that off. It’s not like we have the greatest track record on that scores.

Because I don’t want to end this on a completely negative note, I’ll finish by pointing you to an article about companies that are becoming greener without telling anyone. In some cases, they don’t want to give away corporate secrets—new manufacturing measures that use less water, for instance. In other cases, companies are afraid that people will see the label “organic” and think that they’re going to increase their prices, or that their quality has changed, so they avoid labeling their products.

I bring to mind this article any time I feel especially discouraged. I may not be able to do as much as I’d like myself, but perhaps things are changing as people become more aware. Perhaps we really can innovate our way out of this problem. Maybe—just maybe—the solutions are actually out there.

Feel free to leave a comment about your own angst, and how about you’ve managed it. Please share some ways you’re working to be greener and more eco-friendly. Hacks for reducing reliance on single-use plastics are also welcome. (Also, startup money for a refill shop would be great too. Just kidding, but someone seriously needs to start something like that.)

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!