IN DARKEST LONDON

ACT II.

III.

⸻

“The ticketing agent for the Great Western says the trains to Notting Hill run every half-hour,” Charley told Verochka.

Charley and Verochka were tired and out of spirits—a disposition aggregated by the ten-hour trip on the Mail Boat from Ireland.[1] With their wedding in London just days away, Charley and Verochka could only spend a few days mourning the death of Ina with his family.

“Charlushka, let us take a cab.”

Cabman at Victoria Station.

Outside the terminal there was a small, mixed fleet of cabs and hansoms. The increase in the number of omnibuses and tramcars in London had cut into their trade. They were a desperate group.[2] The driver of a rather dilapidated carriage aggressively approached Charley.

“Where to, sir?”

“Holland Park,” said Charley. “Number 17, Lansdowne Road.”

“B’ysworter, near the Addison Road Station?”[3]

“Yes,” Charley replied confidently. (Cabmen were notoriously overly-liberal in their estimations of distance—and their quote of fare.)

“How’s about 5s?”[4]

The dreary drizzling rain pattered on their bags. Charley, a famously light sleeper, nodded his consent drowsily.[5]

Careful not to slip on the wet buggy-steps, the passengers slowly took their seat. The gentle showers and accumulated mist made a lullaby of the carriage, and Charley dreamily traced the thoroughfares with his eyes. The gaunt houses that lined the fashionable quarters of the town looked back with foggy windows in stationary somnambulism.

This peace, however, was interrupted.

“A postal telegram was received by the Metropolitan police a night or two ago,” said the cabman. “It was addressed to Police Commissioner Warren—the ‘Ripper’ says e’s got ‘several bottles of blood underground in Epping Forest.’ Inspector Abberline is inpectin’ it now.”[6]

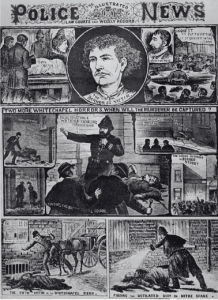

October 6, 1888, issue of The Illustrated Police News.[7]

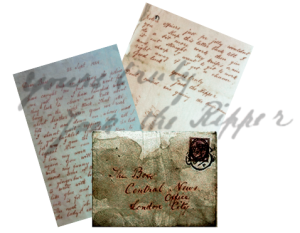

In the time that Charley and Verochka were away, a series of ghastly murders occurred in Whitechapel. The first of these deaths occurred on August 31, with the death of Mary Ann Nichols. Some called the murderer the “Red Fiend,” others, like the prostitutes of Whitechapel, preferred the name “Leather Apron.” These copulate capitalists believed that the killer was the same man who “wore such a garment,” and was known to intimidate them with threats and acts of violence. Accounts in The Star (London) played upon the resentment of immigration among the residents of Whitechapel, by reporting on the murders with a decidedly antisemitic slant. “[‘Leather Apron’s] name nobody knows, but all are united in the belief that he is a Jew or of Jewish parentage, his face being of a marked Hebrew type.”[8] On September 8, 1888, a second victim, Annie Chapman, was claimed. On September 30, the bodies of Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes were discovered, the third and fourth victims being murdered within an hour of each other. On October 1, the police made public a letter their possession, signed by the murderer. The world now knew that the Whitechapel murderer went by the name, “Jack the Ripper.”

“Dear Boss” letter.

“17 Lansdowne Road…so, you lot are Theosophists?” said the cabman with a boldness suggesting drunkenness.[9] “Why ‘aven’t you lot been called in to detect the Whitechapel murderer? If there is anything in your creed, you can surely summon an Adept from Tibet and put him on the track of the ‘Terror’ like a moral bloodhound. Of course, it is no use asking the Spiritualists to do anything. Their visitants prefer driveling on about Carlyle to doing an honest day’s—er, night’s—work.”[10]

~

“When Aunt Lelya and my mother were little girls, they spent a year Pskov,” said Verochka. “There were manifestations of material things, like knocking, and ‘invisible musicians’ who played on a locked piano. Ghosts! Ghosts constantly appeared, visible not only to Aunt Lelya, but also to others—their father, villagers, and most often their little sister, Liza…”

Charley looked startled for a moment.

“From the second wife of their father,” Verochka explained. “These ghosts were immediately recognized by the old-timers, for they were the spirits of the former owners and inhabitants of the village—old people and their children who had long been lying in the chapel behind the pond. None of my family had any idea about the old staff of the estate, having not even seen a single portrait of the former landowners. Most often, the shadow of a bustling, fat old housekeeper, whom even the whole young household remembered, and the ghost of old Shusherin, who was easy to recognize, because he suffered from the Lithuanian hair disease in the last years of his life and wore a klobuk.” Verochka gestured the shape of the hat while struggling to find the proper translation, “a high black oilcloth hat.”

Charley gave an attentive and encouraging nod to indicate that he was following the story.

“Aunt Lelya frightened my mother one spring evening when they were walking in the flower garden. Aunt Lelya was gazing out the windows of the room on the lower floor; smiling and bathed in sunlight, she described the ‘ghost of an old man in a klobuk, with nails as long as claws.’ It horrified my mother, and she told Aunt Lelya to never to tell her about her visions again. Without mentioning Lelya’s visions, they carefully questioned the old gardener, and other people of the house, about the identities of the former owners. They discovered that ‘the old master had a tangle; could not cut his nails; did not cut his hair, and wore a high hat made of oilcloth.’ Aunt Lelya’s channeled messages: predictions, facts, explanations to cases incomprehensible to her family, delivered, sometimes, in Latin or unknown languages, eventually ceased to amaze them. This gave their father the idea of compiling the history of his house, and they spent many entertaining evenings in the company of their ancestors, ‘the noble knights and counts of Han-Han-von-der-Rottergan,’ whose title and second surname were lost by their great-grandfathers when they moved to Russia…at least that is what the restless esprits frappeurs claimed.

“My grandfather, Pyotr Aleksevich Han was distinguished throughout his life for a skeptical tendency of mind. When everyone surrounded his eldest daughter in amazement, claiming that she was a miracle-worker, he alone, it seemed, was convinced that she was ‘fooling the public,’ and said that if he went along with Aunt Lelya’s fairytales, people would lock him away in an asylum. Only after Lelya and my mother implored their father to ask a ‘mental question,’ did he change his mind. He asked a question about a completely insignificant fact of his early youth, completely unknown to anyone, and almost forgotten to himself. He wrote down his answer on a piece of paper and hid in his pocket. ‘Bunny,’ Aunt Lelya said. Their father’s face changed, and for the first time approached Aunt Lelya, interested, and amazed. On the piece of paper, he wrote: ‘What was the name of the horse on which I rode during my first campaign?’ On the reverse side of the question, he himself wrote the name, ‘Bunny.’ Their father eventually became an ardent spiritualist who spent days and nights conversing with the dead.

“Soon the fame of omniscience and the amazing miracles that took place in their village deprived them of any peace. Letters and visitors kept pouring in—especially after one particular incident when “Elena’s spirits,’ provided an official service by assisting the local police. Officer Novorzhevsky arrived in their village to interview people about a murder committed in a nearby a tavern. He initially came to their home just to drink tea. He was, of course, rather indifferent, if not skeptical, about the proposal to ‘ask the spirits,’ but when Aunt Lelya, or rather, ‘they,’ gave him correct information pertinent to the case, Novorzhevsky changed his tone. He was not even upset with their unflattering message: ‘You old twit, here you are drinking a cup of tea while the murderer is preparing his leave for another country! Go now to such and such a village, and there you will find him in the attic of such a peasant.’ Novorzhevsky wrote down the testimony and flew in hot pursuit. The following day he sent word that everything ‘they’ told him turned out to be true. He captured the murderer exactly where the spirits indicated!”

The cab jostled over the rough stones of Notting Hill, stirring the passengers to alertness as they passed the “dead wall” of Holland Park.

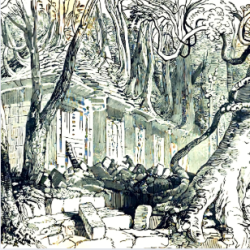

17 Lansdowne Road.[12]

← →

THE AGONIZED WOMB OF CONSCIOUSNESS SECTIONS: “ACT II”

I. THE LITTLE TOY TEMPLE ON NASSAU STREET.

II. UNION OF HEARTS.

III. IN DARKEST LONDON.

IV. NONSENSE OF BROKEN TEACUPS.

V. A CURIOUS REUNION ON WALNUT STREET.

VI. GLORIFIED IN THE LAND OF BABYLON.

VII. ALWAYS THIN AND GRAVE.

VIII. ET IN ARCADIA EGO.

IX. THEORY OF UTILITY.

X. APOLLO BUNDER.

XII. THE SILENT PASSENGER.

XIII. DECCAN PLATEAU.

SOURCES:

[1] Hamilton, Walter. Parodies of the Works of English & American Authors: Vol. IV. Reeves & Turner. London, England. (1887): 44; Black, Adam; Black, Charles. Black’s Tourist’s Guide to Ireland. Adam and Charles Black Firm. Edinburgh, Scotland. (1888): 98.

[2] In 1887, 1,0333 cab drivers were convicted for drunkenness. [“The Police Report.” The Saturday Review. Vol. LXXII, No. 1,868. (August 15, 1891): 182-183.]

[3] A London driver’s “accent” from this period can be found in: [Reinganum, Percy E. “Borrowing a Parrot!” The London Magazine. Vol. VIII. (February 1902-July 1902): 557-564.]

[4] Fare prices:[L.C. “Curing Corns in London.” The Stethoscope. Vol. II, No. 10. (October 1852): 580-582.]

[5] Johnston, V. V. “Letters of Vera Johnston,” December 26, 1888, Adyar, India, entry.

[6] “The Whitechapel Murders.” The Newcastle Evening Chronicle. (Northumberland, England) October 6, 1888.

[7] “Two More Whitechapel Horrors. When Will the Murderer be Captured?” The Illustrated Police News. (London, England) October 6, 1888.

[8] “Leather Apron.” The Star. (London, England) September 5, 1888.

[9] In 1887, 1,0333 cab drivers were convicted for drunkenness. [“The Police Report.” The Saturday Review. Vol. LXXII, No. 1,868. (August 15, 1891): 182-183.]

[10] “Waifs And Strays.” The Weekly Dispatch. (London, England) October 7, 1888.

[11] From a draft of Chapter II in Vera Petrovna Zhelihovskaya’s “Radda Bai.” (1892) [Bakhmut Roerich Society.]

[12] Tingley, Katherine. Helena Petrovna Blavatsky. Aryan Theosophical Press. Point Loma, California. (1921) Frontispiece.