by Cindy Kunsman

Continuing the ongoing discussion of cognitive bias, explaining a puzzle piece as to why we humans cling so tightly to belief systems like Quiverfull and more. Today, let’s recap what we should already know, but when it comes to our own ideas, we tend not to believe that we’re so subject to our nature.

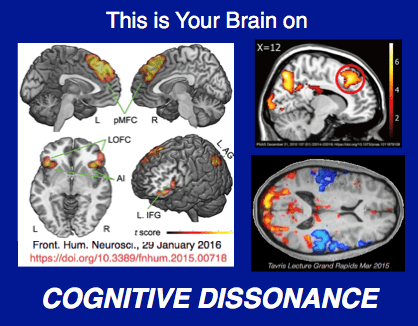

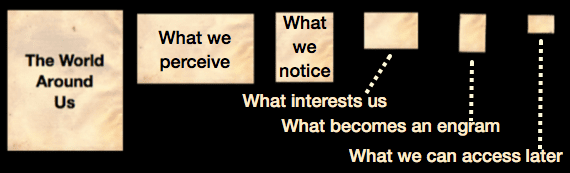

To truly understand the serious discomfort of Cognitive Dissonance, one must take the most basic assumption of human beings as a logical starting point: that the information that we notice represents objective reality in a reliable fashion. If you’ve seen the film, The Final Cut, you may know that our minds tag information with all sorts of things that are not facts so that we can best store and access them, but they are not a true measure of reality. (If we are lucky, we remember those things that are most important in a way that is realistic ‘enough.’) As the diagram below attests, we are very selective about what we remember, and even those things are used to tell a story – usually one that we like to hear.

We also use introspection to measure our own thoughts and feelings, but we always make the assumption that we are fair and kind – or at least as much as the next guy. And because of our aversion to cognitive dissonance, we also assume and assure ourselves that our motives can only be good and honorable.

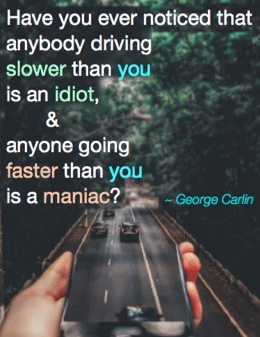

We also assume that our own behavior represents sensibility and represents the standard of what is right and true. Like George Carlin’s old joke, we perceive that those who drive slower than us on the highway are driving too slow, and those who drive faster drive too fast. We assign ourselves with the reasonable standard against which we understand others, and if we are reasonably healthy in mind and soul, we always find ourselves in the right. Anything else causes cognitive dissonance because it challenges who we are, suggesting that we’re not the good, competent, reasonable people that we like to think we are. Almost like a twist on Protagoras, in most things, we see our own perspective as thoughtful and circumspect – and it serves as the primary root of all cognitive dissonance.

Once we decide upon any position, our ego goes to work and beings to close our thoughts around that decision. We will no longer accept alternatives as valid as our own, and all of the other aspects of our self will conform to our decision to reinforce our sense of consistency. Information to the contrary suddenly seems suspect, and we cast disparagement on anything that suggests error. (Asking someone who just bought a car whether they thought that they made a right decision is the worst time to do so. They will be biased in favor of their purchase because they cannot afford the cognitive dissonance generated by a different choice. Unless they landed a grand lemon, they will think that their own choice is best.)

Naive Realism

This bias that coddles our ego with good thoughts also extends to how we perceive others and what we can anticipate when we interact with them. Unless past experience has taught us otherwise, when seeking a desirable outcome, we can project our own sense of reason-ability on to others. We again hold our own understanding of ourselves as the standard, but we really have no way of knowing what others are thinking and feeling. (Often, others are not even acting thoughtfully, and it’s likely that even fewer have a well-developed sense of self-awareness.) This assumption has been dubbed Naive Realism, and this bias always casts us in a positive light.

In some sense, then, cognitive dissonance theory is really one of blind spots. It’s not willful, but it becomes an unintentional bias that avoids anything that will give us cause to question our beliefs, convictions, or behaviors – and our neatly corresponding sense of self. In the beginning of a paradigm shift, we will doubt or discredit those things that challenge us until we hit a tipping point that demands that we reckon with them. This drive for comfort motivates us as powerfully as hunger and thirst, and we all become subjects in its service as it serves its purpose for us. It’s one of the many gifts and curses of our humanity. And if we are lucky enough, we become grounded in enough biases that are good enough. Some of us learn by crawling out of them after they’ve taken their toll, while some of us perish while still entrenched in them.

Further Reading:

Gilovich and Ross’ The Wisest One in the Room

Tavris and Aronson’s Mistakes Were Made

McRaney’s You Are Not So Smart

Gilovich’s How We Know What Isn’t So

Cindy is a nurse who was raised in Word of Faith, a Second Generation Adult of cultic Christianity. She and her husband dabbled in Calvinism and Theonomy as a foil to Christian anti-intellectualism, and they were exit counseled together when the walked away from a church that embraced Gothard’s teachings. Cindy escaped many Quiverfull pitfalls but became a social pariah for failing to birth a family. She’s been decrying the abuses of the Patriarchy Movement since 2004, and she writes about spiritual abuse at her blog, Under Much Grace. Read more about her here.

Stay in touch! Like No Longer Quivering on Facebook:

If this is your first time visiting NLQ please read our Welcome page and our Comment Policy! Commenting here means you agree to abide by our policies.

Copyright notice: If you use any content from NLQ, including any of our research or Quoting Quiverfull quotes, please give us credit and a link back to this site. All original content is owned by No Longer Quivering and Patheos.com

Read our hate mail at Jerks 4 Jesus

Check out today’s NLQ News at NLQ Newspaper

Contact NLQ at [email protected]