O Come O Come Emmanuel

Fusing Our History with Ancient Israel’s History

Kathryn Shihadah’s Patheos post, “Reflections on ‘O Come O Come Emmanuel,” reminded me of an insight I once had. Let me retrieve it to see what you think about it.

I had been invited to preach a homily at a large Methodist church in Singapore on the First Sunday in Advent. Oh, yes, the opening hymn was ‘O Come O Come Emmanuel’. I stood to sing. From the chancel I could see all that was going on. The 350 worshippers were largely Chinese. Families. Lots of buzz. Mothers grabbing very active children who wanted to run. The singing was robust, enthusiastic, spirited. The singing was in English.

This particular church offered five worship services on Sunday, each with its own language: English, Cantonese, Mandarin, Malay, and Tamil. I had been slotted for the English service, thank goodness. That does not mean anyone from England would be worshipping. These English speakers and singers were mostly Chinese.

O Come O Come Emmanuel

We belted out, ‘O Come O Come Emmanuel‘ as the choir marched in. This 8th century poem, Veni Veni Emmanuel, was translated into English in 1851 by John M. Neale.

Pause for a moment. Imagine that you live in ancient Israel. You’re sick ‘n’ tired of empire. You’re sick ‘n’ tired of domination by foreign rule by Assyrians, Babylonians, Greeks, and Romans. You want liberation. You’re looking forward to the advent of the Messiah. Might you pine these lyrics?

O come, O come, Immanuel,

and ransom captive Israel

that mourns in lonely exile here

until the Son of God appear.

Refrain:

Rejoice! Rejoice! Immanuel

shall come to you, O Israel.

The yearnings of our Israelite ancestors become our yearnings as we sing this Advent hymn.

Give a History

Ooops! Our Israelite ancestors? Genetically speaking, these Chinese worshippers have no relationship whatsoever to the Israelites. Their blood line goes back to China, not Israel. So, what’s going on here?

I’m an American. None of my genetic forbearers came from Israel either. They came from America. And before that from central Europe. So, what’s going on here?

What about language? The ancient Israelites spoke Hebrew. Jesus spoke Aramaic. The New Testament is written in Greek. These worshippers grew up speaking Cantonese or Mandarin. I grew up speaking English.

Every language embodies its cultural history, hermeneutical philosophers tell us. Let’s count them: Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek, Chinese, and English. Five or more languages each with its distinctive cultural history were merging that Advent Sunday into a single hymn being sung by an international and multi-racial community of worshippers. So, what’s going on here?

When drinking tea following worship, these English speaking Chinese Christians chatted with other Christians speaking Malay, Tamil, and different versions of Chinese. So, what’s going on here?

What about geography? I suspect that very few if any of the Chinese worshippers that Sunday had ever visited Israel. Maybe as tourists. China? Yes, very likely. And the language these Chinese were speaking, English, came from some islands off the west coast of Europe, nowhere near Israel. So, what’s going on here?

Here is my observation. What has happened here, among other things, is that when we become Christian we are given a new history. Our previous cultural and linguistic history does not go away, to be sure. But, Israel’s history becomes our own history. It is within the context of Israel’s history that the transcultural, global, and even cosmic significance of God’s incarnation in Jesus Christ becomes meaningful.

Here’s the point. We add a history. We don’t take other histories away.

Deconstructionist, Postmodernist, and Postcolonial Pluralism

That we add histories rather than take them away is a point missed by our deconstructionist, post-modernist, post-colonialist, and pluralistic colleagues. The laudable goal of this school of progressive theology is to liberate indigenous cultures from the hegemony of dominant empires. The term post-colonial, according to Kwok Pui-Lan, “denotes not merely a temporal period or a political transition of power, but also a reading strategy and discursive practice that seek to unmask colonial epistemological frameworks, unravel Eurocentric logics, and interrogate stereotypical cultural representations” (Kwok, 2005, 2). For today’s postcolonialists, the European empire replaces the Assyrian, Babylonian, Greek, and Roman empires.

The problem, according to today’s postcolonialists, is that the Eurocentric narrative has marginalized previously colonized peoples. The task of today’s theologian, then, is to destabilize Europe’s narrative by reviving indigenous non-Western approaches to theologizing the Bible which have been squashed under the weight of colonial interpretations of history. Even European hermeneutical methods are becoming revised so that our inherited Bible can become “comprehensible to the colonized cultures on their own terms” (Steele Ireland, 684). Here is South Korean public theologian Paul S. Chung.

“Postcolonial theology attempts to transcend the aftermath of colonialism by moving beyond the colonial or neocolonial forms of global domination…[beyond] the panopticon of globalization [that] enforces a homogenization of narratives, forgetting and trampling over the countless indigenous and subalternized stories” (Chung, 2022, 187).

Israel sought to de-colonialize itself from one empire, Rome. Today’s postcolonial theologian seeks to de-colonialize every indigenous people from one empire, Europe. Might these two have something in common? Try singing, “O Come O Come Emmanuel.”

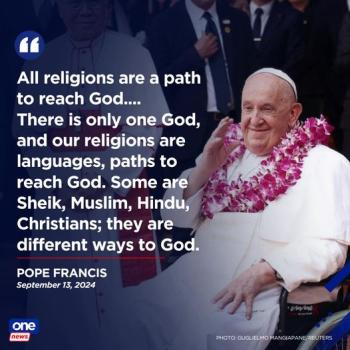

Permanent Pluralism versus Christian Unity

Tacitly and perhaps unconsciously, however, the goal of the postcolonial pluralist is to end up with a plurality of subcultures that are independent, contiguous, and no longer in relationship. Plurality becomes the value that drives the ideology of pluralism. The fabric of social or cultural unity is rent, torn into scraps of separatist self-interest groups. This obtains even if it means rending the communal unity of the Christian church worldwide. Whether indented or not, this seems to be the logical goal of postcolonial pluralism.

According to one of the progenitors of public theology, David Tracy, “there is a price to be paid for any genuine pluralism–that price many pluralists seem finally either unwilling to pay or unable to see. It is that there is no longer a center “(Tracy, 1994, 4). Neither a center nor a sense of unity in historical consciousness. Unless, of course, the historical consciousness of ancient Israel merges with the contemporary consciousness of each liberated postcolonial subgroup.

Now, as you can see, I contend that our churches should strive for oneness in Christ. This striving for unity fuses histories, fuses cultures, fuses consciousness. Hermeneutical philosopher Hans Georg-Gadamer called it the “fusion of horizons” (Horizontverschmelzung) (Gadamer, 306) . Our worldwide ecumenical Christian consciousness is constantly undergoing dynamic growth in understanding through the giving and receiving of somebody else’s history. Plurality gets complemented by fusion–that is, by unity in diversity.

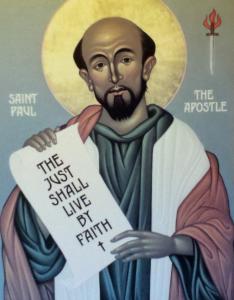

Reinterpreting St. Paul

St. Paul treats Christian unity with a “neither…nor.”

There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus. And if you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s offspring, heirs according to the promise. Galatians 3:28-29)

How about a “both…and” interpretation?

How about a “both…and” interpretation?

What empirically happens, I think, is that the Christian church ends up with both Jew and Greek, both slave and free, both male and female along with nonbinaries of many types. The logic is the same in that none are subordinated to the other. Yet, our historical consciousness is a fusion of a plurality of histories.

Our Christmas Meditations Thus Far

Christmas Meditation 1: God Desired a Harlot with St. John Chrysostom

Christmas Mediation 2: The Word Became Flesh with St. Augustine

Christmas Mediation 3: Truth at Christmas with St. Augustine

Christmas Mediation 4: Mean Estate with Martin Luther

Conclusion: O Come O Come Emmanuel

O Come O Come Emmanuel and ransom captive Israel. And, while your at it, Emmanuel, ransom the rest of us as well.

▓

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor. He is author of Short Prayers and The Cosmic Self. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). His book, God in Cosmic History, traces the rise of the Axial religions 2500 years ago. He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his new, The Voice of Public Theology (ATF 2023). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Ted Peters’ fictional series of espionage thrillers features Leona Foxx, a hybrid woman who is both a spy and a parish pastor.

▓

References

Chung, Paul S. (2016). Postcolonial Public Theology: Faith, Scientific Rationality, and Prophetic Dialogue. Eugene OR: Cascade Books.

Gadamer, Hans-Goerg (1994). Truth and Method, tr. Joel Weinsheimer and Donald G. Marshall. New York: Continuum, 2nd ed.

Kwok Pui-lan (2005). Postcolonial Imagination and Feminist Theology. Louisville KY: Westminster John Knox Press.

Steele Ireland, Marèque (2008). “Postcolonial Theology”. In Dyrness, William A.; Kärkkäinen, Veli-Matti (eds.). Global Dictionary of Theology. Nottingham: InterVarsity Press. pp. 683–687.

Tracy, David (1994). On Naming the Present: God, Hermeneutics, and Church. Maryknoll NY: Orbis.