Can neuroscience debunk mystical experiences? Should we dismiss them as a matter of misfiring neurons, or are they something more something more?

In the first two posts of this series (here and here) I reviewed novels that explore these questions with nuance and complexity. Here, I argue that neuroscientific explanations do not threaten mystical experiences, once we reject a false materialist framework.

What is mysticism?

First, we have to define our terms. Mysticism is the tendency of the human soul toward the divine, most often through contemplation in love. Importantly, it’s not the capacity of an individual to grasp the mysteries of God by her reason. Rather, it’s a particular gift of divine grace. It’s God’s action to allow the person to intimately contemplate His being.

As is written in the Catechism, “When he [or she] listens to the message of creation and to the voice of conscience, [the human person] can arrive at certainty about the existence of God, the cause and the end of everything.” (46)

Defined in this way, mysticism is essential for a full and flourishing Christianity. In the words of Pope Francis, “A religion without mystics is a philosophy.”

Mystical experiences are rich, varied and complex. As such, it’s difficult to identify a common denominator, even in terms of the psychological aspects of the experience. However, most mysticism involves the experience of transcendence, as well as feelings of wonder and awe. These are usually brief, and may change one’s sense of time and space, but feel overwhelmingly real.

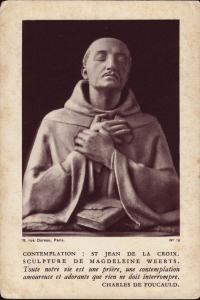

In the Christian tradition, mystics pursue a three-part path: purgation, illumination, and unification with God. The purification often takes place through ascetic discipline. Illumination, then, is the Holy Spirit’s action to enlighten the mind. Finally, the unitive phase is the experience of being joined to the Divine being, especially God as love.

Can neuroscience tell us something about mysticism?

Mystical experiences were brought into mainstream psychological discussion by William James’ foundational work, Varieties of Religious Experience. In his view, they are an altered and irrational state of consciousness, one that is purely subjective and private.

Let me start by stating this: there is a serious gap in the scientific literature when it comes to the neural correlates of mystical experiences. The ones that exist, such as this fMRI study on the brains of 15 Carmelite nuns, are plagued by ambiguously defined terms and categorical errors in their reasoning.

Furthermore, the function of the brain as a whole remains enigmatic. We still don’t understand the way in which complex neural circuits interact and are integrated. We don’t know what underlies altered states of consciousness. Perhaps most importantly, we have no idea how consciousness and all its qualitative subjectivity arises.

Though we have a long way to go, there is great promise here. Identifying possible neural correlates for mystical experiences certainly seems possible, and it could help us understand ordinary brain function as well.

A reductive account of Christian mysticism

However, materialist theories and claims about mysticism abound. More often than not, they hypothesize mystical experiences to be mere byproducts of neuropathological conditions.

For instance, some point to temporal lobe epilepsy as the mechanism of mystical visions and trace-like states. This is the condition on which Salzman modeled his character Sister John of the Cross.

Another idea is that acute and chronic hypoxia — lack of oxygen — generates abnormal patterns of activation at the temporo-parietal junction in the brain. These patterns then cause altered perception and feelings of transcendence and awe. This would account for the concentration of mystical experiences on mountains.

In and of itself, neuropathology does not categorically empty religious experiences of truth or validity.

However, most theorists claim that the neurobiological mechanisms of mysticism are full explanations of such experiences. From this materialist position, the physical processes are not just biological correlates of the experience. Rather, they constitute the whole of the phenomenon. As such, neuropathological origins would reduce mystical experiences to mere delusions generated by the brain. And under these terms, mysticism is necessarily private and devoid of truth beyond mere subjective experience.

But is this an adequate account of mysticism?

Toward a non-reductive account of mysticism

In my opinion, reductionism is a woefully inadequate account of the human person – including human experiences of mysticism. The physical correlates in the brain are just part of the picture, and by themselves, they do not account for the existence or experience of the human subject.

Ultimately, it’s important to remember that neuroscience will not answer the questions of theology. Neuroscience can only play a part in our self-understanding as religious people. Thus, when interpreting and evaluating religious experiences, we must operate under three conditions.

- Tradition. Mystical experiences do not take place in a vacuum of subjectivity but within the larger picture of a tradition. Therefore, they should be evaluated and purified according to the light of established revelation.

- Community. Mystics must be embedded in communities of faith, because their experiences are not for themselves alone. If they are truly grasping truth about God, the experience is not merely subjective but objective. As such, they are a gift for the mystic’s whole community, and must be received and interpreted by that community.

- Gratitude. Mystical experience, and any experience of God, is a mysterious gift. In the end, union with Him is a gift not grasped by will or reason alone. Therefore, mystical experiences should be welcomed with deep reverence and gratitude.

Under these three conditions, mysticism can flourish, and can contribute essentially to a vibrant and authentic Christianity.

Further reading recommendations

Check out my two previous posts in this series here and here.

Here’s a collection of essential writings of Christian mystics, compiled by Bernard McGinn. Lately, I’ve been reading Simone Weil, Julian of Norwich, Evagrius Ponticus, and St. John of the Cross.