“That is how the name came into my heart: Francis of Assisi. For me, he is the man of poverty, the man of peace, the man who loves and protects creation; these days we do not have a very good relationship with creation, do we?”

— Pope Francis on why he chose “Francis” as his papal name

“Pagans Make Common Cause with Catholics to Save the Planet”

It could happen.

It’s been 3 weeks since “A Pagan Community Statement on the Environment” was published and almost 4,000 people have signed. That may not seem like a huge number to people belonging to larger and more centralized religions, but for a group as diverse and decentralized as Pagans, it’s kind of huge. Signatures have come from places as distant from the U.S. (geographically and culturally) as Japan, Zambia, and even Iran! The statement has been translated into 8 languages, with more on their way. By summer solstice — June 21 — we hope to have 10,000 signatures. This will coincide with the Pope Francis’ publication of an encyclical on the environment and is an ideal opportunity to share a Pagan vision of sustainability with the world. As John Beckett recently wrote:

“If the leader of the world’s largest Christian denomination can issue a progressive statement on the environment, why can’t Pagans – most of whom hold Nature in much higher regard than do Christians – do at least as much?”

Pagans vs. Catholics?

Contemporary Pagans and Catholics have always had a complex relationship. Both Pagans and Catholics tend to define themselves in contrast to one another.

For example, it is common for Pagans (myself included) to define our experience of an immanent divinity (whether a pantheistic Goddess or polytheistic deities who are part of nature) in contrast to the transcendental theism of Christians. And we easily take the next step to saying that Christian belief necessarily leads to environmentally unsustainable ways of life. Many early Neo-Pagans adopted Lynn White’s theory that environmental decline was, at its root, a Christian problem. In his 1967 article, “The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis”, White traced the belief that the earth was a resource for human consumption back to the triumph of medieval Christianity over pagan animism, and even further back to the Biblical injunction to man to “subdue” the earth and exercise “dominion” over every living thing. A few years later, in 1972, Arnold Toynbee published “The Religious Background of the Present Environmental Crisis”, in which he traced the cause of environmental destruction to monotheism, which he contrasted with the ancient pagan attitude toward nature. Both White’s and Toynbee’s articles were quoted by Margot Adler in her 1979 survey of Paganism, Drawing Down the Moon. Since then many Pagans have followed White and Toynbee in contrasting the Abrahamic monotheism with ancient paganisms, the former being portrayed as dualistic and anthropocentric, and the latter being portrayed as holistic and eco-centric.

The reality, though, is that the causes of our environmental crisis are more complex. We can neither vilify Abrahamic religions, nor idealize Pagan religions. On the one hand, Abrahamic monotheism has inspired ecological sustainability visions of human life. There are many historical and contemporary examples of this, from the “patron saint of ecology”, St. Francis, and the Catholic priest, don Ramón Vacas Roxo (who is credited with creating the first Arbor Day celebration in 1805 in the small Spanish village of Villanueva de la Sierra) to contemporary eco-Christians like Matthew Fox, Michael Dowd, John Cobb, and Sallie McFague.

On the other hand, ancient pagan and indigenous ways of life have not always been environmentally sustainable. Indigenous peoples of North America, Polynesia and Europe hunted species to extinction. And Europe experienced massive deforestation long before Christianization, as did China, which was never Christianized. (See Arne Kaland’s essay on the myth of the “environmentally noble savage”.) Furthermore, there are doubts as well about whether contemporary Pagan beliefs about the sacredness of the earth actually translate into environmentally sustainable practices. (See the preliminary findings of a survey by Dr. Kimberly Kirner of 800 Pagans about environmental sustainable practices.)

We must conclude that every religion is a complicated mixture of ideas that can be used to either rationalize environmental abuse or encourage ecological harmony.

Catholics vs. Pagans?

Just as Pagans tend to define themselves in contrast to orthodox Christianity, so Catholics and other conservative Christians often define themselves in contrast to paganism — and calling environmentalism “paganism” seems to be all that is required to condemn the former in the minds of some people. The critical distinction for many Christians seems to be an “idolatrous” worship of “creation” rather than the divine “creator”. This was reflected in the 2010 environmental encyclical from Pope Francis’ predecessor, Pope Benedict. Predictably, he described nature as God’s creation and argued that, as such, it should be treated as a divine “gift” to humanity: “Nature is at our disposal not as ‘a heap of scattered refuse’, but as a gift of the Creator who has given it an inbuilt order, enabling man to draw from it the principles needed in order ‘to till it and keep it'”. Pope Benedict went on to contrast the Catholic perspective with what he called “neo-paganism””: “But it should also be stressed that it is contrary to authentic development to view nature as something more important than the human person. This position leads to attitudes of neo-paganism or a new pantheism — human salvation cannot come from nature alone, understood in a purely naturalistic sense.” But he then went on to warn about the dangers of going too far in the other direction:

“This having been said, it is also necessary to reject the opposite position, which aims at total technical dominion over nature, because the natural environment is more than raw material to be manipulated at our pleasure; it is a wondrous work of the Creator containing a ‘grammar’ which sets forth ends and criteria for its wise use, not its reckless exploitation. Today much harm is done to development precisely as a result of these distorted notions. Reducing nature merely to a collection of contingent data ends up doing violence to the environment and even encouraging activity that fails to respect human nature itself.”

Now, it is easy for Pagans reading this to criticize Pope Benedict’s characterization of “neo-paganism” and his anthropocentric vision of nature. However, there is another way to look at it: The 2009 encyclical can be seen as an example of how Catholics and Pagans can arrive at the same place, but by different paths. Even while claiming that human spirit transcends nature and that the Earth was created for human use, Pope Benedict’s statement arrives at the same place as the “neo-paganism” which he eschews: condemnation of exploitation of the earth as a mere resource for humans and recognition of the intrinsic value of nature.

Never the Twain Shall Meet?

I can only guess what Pope Francis’ encyclical will say. Prior statements by him give an indication of the shape it will take. Pope Francis will likely describe environmental stewardship as a Christian duty. He is expected to acknowledge that climate change as largely human-made and to call for bolder action by world leaders. I expect that he will emphasize the disparate impact of climate change on the poor and on underprivileged nations, and he may criticize unchecked capitalism. It is highly unlikely that he will call for population control, or that he will recognize the connection between the patriarchal subjugation of women and the exploitation of the earth. It is possible that he will draw less of a distinction between humanity and nature than his predecessor did, but he may still take a poke at “paganism” along the way.

I can only guess what Pope Francis’ encyclical will say. Prior statements by him give an indication of the shape it will take. Pope Francis will likely describe environmental stewardship as a Christian duty. He is expected to acknowledge that climate change as largely human-made and to call for bolder action by world leaders. I expect that he will emphasize the disparate impact of climate change on the poor and on underprivileged nations, and he may criticize unchecked capitalism. It is highly unlikely that he will call for population control, or that he will recognize the connection between the patriarchal subjugation of women and the exploitation of the earth. It is possible that he will draw less of a distinction between humanity and nature than his predecessor did, but he may still take a poke at “paganism” along the way.

The publication of the papal encyclical is timed to precede the UN Climate Change Conference in Paris this December, the goal of which is to achieve a binding agreement on emission reductions from all the nations of the world. Pope Francis is wildly popular right now, and not just among Catholics. Even the U.S. President is aligning himself with the Pope on this issue. And this Pope has given us lots of reasons to like him — although he has not gone far enough on issues like gender equality and LBGT rights in my opinion. Still, from a Pagan perspective, I think Pope Francis’ encyclical on the environmental can only be a good thing.

I am noticing a certain irony in the Pagan habit of defining ourselves in contrast to Christians (“We’re completely different!), while at the same time snidely thumbing their noses at them by pointing out all the vestiges of ancient paganism in modern Catholicism (“Look how similar we are!”). And I am coming to doubt what has become a Pagan article of faith for some (including me): that the Christian belief in a transcendent deity necessarily leads to environmental desecration in practice. It is probably no more true than the Christian notion that the Pagan belief in an immanent divinity necessarily leads to amoral hedonism.

I wonder if the timing of the publication of “A Pagan Community Statement on the Environment” and the papal encyclical on the environment might be an opportunity for the beginning of a rapprochement between our communities. This will be difficult for both sides, especially for many Pagans whose faith of origin was Catholicism. But I am beginning to wonder what good it does for Pagans and Catholics to cultivate these feelings of superiority to one other. What does this this serve? Our egos more than the ecosystem, surely. Perhaps both sides might consider the possibility that we are not seeing each other clearly. Rather, we have both set up “straw men” of one another. When Catholics talk about “paganism”, it never seems to me that they are really talking about us, but rather some bogeyman of their own imagining. And perhaps my own image of Catholicism is no more accurate than the Catholic image of Paganism — merely another convenient, but inaccurate “othering”. It can be difficult to see this sometimes, immersed as we are in our distinct paths. But when we suddenly find those paths intersecting, as they are at this moment, perhaps we can reconsider whether we — and all other life on Earth — would be better served by emphasizing our similarities, rather than our differences.

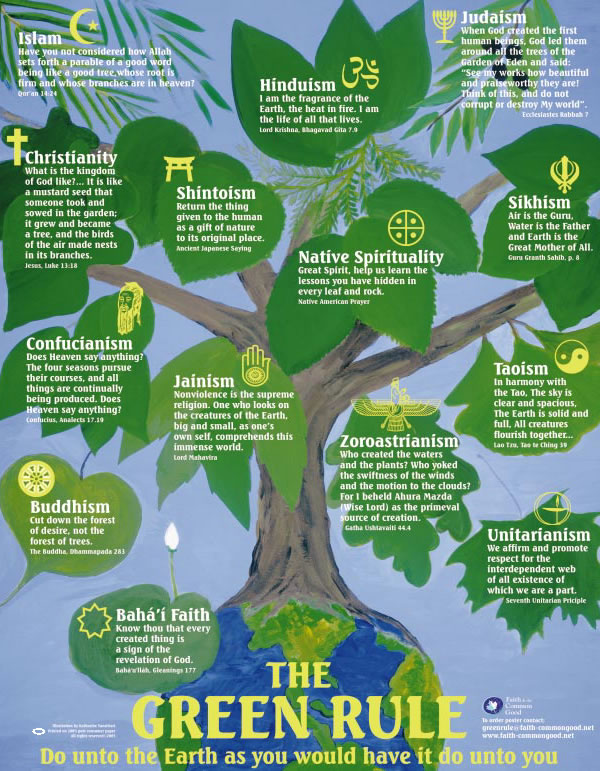

This would not be the first time this happened. In 1986, the World Wildlife Fund brought together Christian, Muslim, Jewish, Hindu and Buddhist leaders, to prepare separate declarations on the environment, each reflecting their distinct commitment to the care of the natural world. These came to be known as the “Assisi Declarations”. Seven other faiths subsequently joined with the original five in the Alliance of Religion and Conservation (ARC) and produced statements of their own. What I find remarkable is that no dilution or homogenization of belief or practice was required for this to happen. None of these of these religions had to give up anything distinctive about their expression of their respective faiths in order to join their voices in this interfaith effort. It was this effort, in part, which inspired me to call for a Pagan community statement on the environment. And I hope that the Pagan statement will be added those of the other religions recognized by ARC.*

In the meantime, whether or not Pope Francis explicitly mentions Paganism in his environmental declaration, I expect there will be talk about Paganism in the media. In fact, there already has been. Let’s draw on the momentum created by the anticipation of the publication of Pope Francis’ environmental declaration, and spread the word about “A Pagan Community Statement on the Environment”. If you haven’t signed yet, you can go to ecopagan.com to read the statement and sign it. If you have already signed, you can share the statement with 5 Pagan friends in a personal email or personal Facebook message. And if you belong to a Pagan organization that has a mailing list, email list or newsletter, ask someone in the organization to promote the statement to its members.

*Note: Thus far, ARC has politely declined our efforts to include “A Pagan Community Statement on the Environment” among those of the other world religions. But I am optimistic that ARC will come to see the value in adding a Pagan voice to those of the other faiths represented there. Getting 10,000 signatures for “A Pagan Community Statement on the Environment” may help move us in that direction.