“These are some of the comments and messages that I received in response to my last couple of posts about “Why I Am ‘Still’ A Pagan” and my reply to John Beckett’s response“:

“These are some of the comments and messages that I received in response to my last couple of posts about “Why I Am ‘Still’ A Pagan” and my reply to John Beckett’s response“:

“What you said in this article, about polytheist beliefs leading to the same alienation that causes disenchantment–that’s about the most fucked up thing I’ve ever heard you say”

“A very well-written post, thank you for writing it! It’s ruffling a lot of feathers, but this religion needs a little ruffling from time to time.”

“No, I don’t agree with you. But I didn’t lose respect for you or begin to dislike you until you stopped pretending to not be an asshole.”

“I think you’re a really important part of the Pagan community. We need people like you to stir things up, to show that we are serious, and to make room for people like me. … It is blogs like yours that keep me calling myself a Pagan. …”

“… sometimes I think you’re Teo Bishop 2.0. You’re relatively new to Paganism, came from Christianity, resist doing a lot of historical homework, and have a lot of criticisms that you frame in a very sensational, controversial way.”

“This may be my favorite post you’ve written so far, John. It perfectly encapsulates my own qualms with the current state of Pagan theological discourse, and it’s sure to prompt a lot of discussion.”

“Much of the time you write words worth considering and share important wisdom, but it’s couched such defensiveness, dismissiveness and snideness in tone, that [it’s] hard to get past.”

“As a scientist, atheist and pagan, I thought this was a perfect mirror of my own thoughts, and some of the comments are the very reason that there isn’t more critical thinking and objective discussion within the pagan (and all other religious) community.”

This past week, while I’ve been on vacation in Portlandia, I took a break from blogging to mull over all this, and there’s one thing I keep coming back to:

“Internet Paganism is not Paganism.”

It’s not just that those involved in internet Paganism probably represent less than 0.25% of Pagans. It’s that the discussions that happen on the internet are not Paganism. They are discussions about Paganism. And I think different rules apply when we’re talking about Paganism than apply when we’re practicing Paganism.

Connecting with the land and it’s other-than-human inhabitants, celebrating the Wheel of the Year, worshiping gods, venerating ancestors, meditating, praying at your shrine, pouring libations, making offerings: these kinds of things are Paganism.

This blog is not Paganism. (And commenting on this blog is not Paganism.)

Paganism and the Critical Gaze

Recently John Beckett has written a couple of posts about the place of the critical gaze in Paganism. The first, which was directly responsive to what I had written, was titled “You Can’t Practice Paganism While Looking Down Your Nose At It”. I agree with that statement, if by it he means you can’t practice Paganism at the same time you are critically analyzing it. But I disagree with the implicit suggestion that there is not a time and place for critical analysis of our Paganism. Critical analysis of Paganism and practicing Paganism are not the same thing. And they can’t be done at the same time. But that doesn’t mean we have to choose between them. There is a time and place for both.

Recently John Beckett has written a couple of posts about the place of the critical gaze in Paganism. The first, which was directly responsive to what I had written, was titled “You Can’t Practice Paganism While Looking Down Your Nose At It”. I agree with that statement, if by it he means you can’t practice Paganism at the same time you are critically analyzing it. But I disagree with the implicit suggestion that there is not a time and place for critical analysis of our Paganism. Critical analysis of Paganism and practicing Paganism are not the same thing. And they can’t be done at the same time. But that doesn’t mean we have to choose between them. There is a time and place for both.

John’s second post on this issue is entitled, “My Paganism Has No Disclaimers”. John writes:

“When you constantly put disclaimers on your beliefs, you undermine the positive effect those beliefs have on your life. You tell yourself “maybe it’s not true” and so when things get complicated – or just hard – you’re far more likely to stop acting in accordance with those beliefs. Disclaimers empty beliefs of their power.”

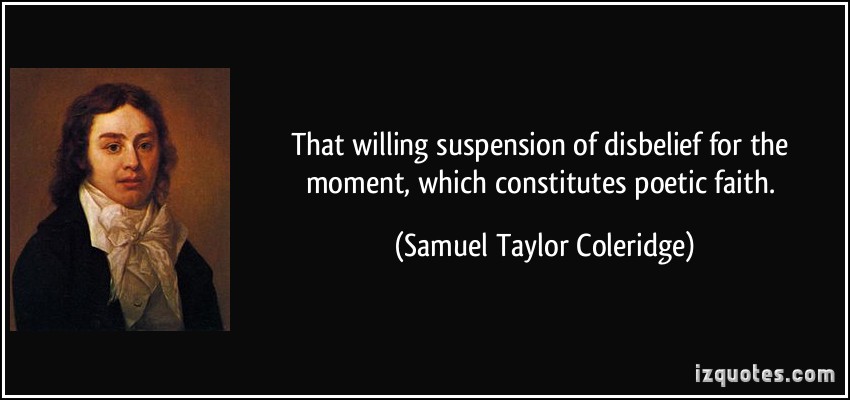

That is a recipe for fundamentalism and fanaticism. I agree that we can’t practice Paganism while our minds our flooded with disclaimers or qualifications. For example, the part of our minds that is concerned with such distinctions should be in a state of suspended animation during ritual in order for us to connect with the divine “other” (however we conceive it). But I disagree with John’s suggestion that there is no place for disclaimers when talking about Paganism.

Mythos and Logos

In a recent article on “Faith and Belief”, Yvonne Aburrow highlighted the distinction between the language of logos and mythos. Logos is related to reason and science and is a pragmatic mode of thought which enables us to control our environment. This is the language in which most of this blog is written. Mythos, on the other hand, is related to myth and enables us to live meaningful lives. It deals not in propositional truth, but in stories. Through logos we relate to the world of objects. Through mythos we relate to a world of subjects. Logos enables us to survive; mythos enables us to thrive. (The logos/mythos distinction is similar to the distinction drawn by Michael Dowd between “Day Language” and “Night Language”.) Neither one is better than the other. We need both.

John Beckett argues that there is a kind of “belief” which has nothing to do with propositions (logos), and everything to do with values (mythos). I think calling them both “belief” is confusing, but whatever you call it, we need to be clear about which kind of language we are using. Much of the practice of Paganism occurs in the mythic dimension. But internet Paganism is a different matter. Some of what we read on Pagan blogs is mythos; it may be poetry, invocation, story, or a personal account of a transformative experience. But most of internet Paganism is logos; it’s using the language of logic to critically analyze Paganism. It is talk about Paganism, not the practice of Paganism.

And conflating the two leads to a lot of confusion and frustration. Saying you value something is not the same thing as saying that you believe a certain proposition to be true. Saying that your relationship to your gods is dear to you is not the same thing as making a statement about the metaphysical nature of the gods. Saying you experience the gods as individuals is not the same thing as saying that you know the gods are distinct metaphysical beings. Consequently, doubting the independent existence of the gods does not have to undermine your practice of paying devotions to them. And a blog post that criticizes literalistic theism does not have to be read as an attack on your relationship with your gods.

Suspending Disbelief

Several months ago, I wrote a post — using the language of mythos — about the danger of logos. I described logos as a knife, which has the power to bring order to life, but also the power to “kill” the living quality of experience. Someone recently reminded me of that post, obviously feeling that I had forgotten it. It’s true that the language of rational discrimination and critical analysis has the potential to get in the way of religious experience. As natural polytheist Alison Leigh Lilly has written in an essay entitled “Anatomy of a God”:

Several months ago, I wrote a post — using the language of mythos — about the danger of logos. I described logos as a knife, which has the power to bring order to life, but also the power to “kill” the living quality of experience. Someone recently reminded me of that post, obviously feeling that I had forgotten it. It’s true that the language of rational discrimination and critical analysis has the potential to get in the way of religious experience. As natural polytheist Alison Leigh Lilly has written in an essay entitled “Anatomy of a God”:

“This is the dilemma of theology … We want so very much to understand our gods, to know them intimately, to see how they work in our lives. It is tempting to dissect, to analyze, to categorize. And sometimes, it is necessary, even beneficial. We are categorizing creatures, we human beings. We pick out patterns as a matter of survival. When it comes to our gods, we reach for them not only with our prayers and offerings, but with our reason and our intellects — we would know them with our whole selves, in all their parts, in part so that we might know our own selves better in all our parts. The challenge is to delve into theology without killing its subject, to try our hand at analysis and critical thinking without pretending that the numinous divine is a dead thing that will hold still beneath our careful knives. Theology is not dissection. It is much more gruesome than that; it is vivisection.”

This is challenge for many Pagans, but one that Humanistic Pagans, like myself, especially struggle with. D.T. Strain has written about the how the objectivity of religious naturalists interferes with our subjective experience: “We cannot achieve greater subjective intuitive experience through greater objective intellectual knowledge alone. We are still holding on to the edge of the pool, scared to float.” No matter how much we learn about a religious practice, says D.T., we will never be able to evaluate their worth until we experience them from a different mindset. “This is because they are inherently subjective experiences. The way you investigate them is by engaging in them without reservation – to be willing to make a leap.” D.T. writes:

“Many of we rationalists, Humanists, etc. who aim to approach naturalistic spirituality sit against the wall at the dance, talking with one another about the dancers out on the floor. We analyze their movements and critique their techniques. Then we speculate about the biological underpinnings of their enjoyment of the dance. We might even present studies on the neural correlates of dancing. We imagine that this discussion and knowledge somehow gets us closer to being good dancers or to sharing in that enjoyment. Then the lights come on, the party is over, and we go home completely failing to have ever danced or even understood what the experience of dance is like or how it really feels.”

Suspending Belief

But there still remains a role for critical analysis and rational discrimination in talking about religion, including Paganism. We still have a need for that “knife”. For the same reason that we prune plants and weed gardens, we also need to prune our experiences with Ockham’s razor and weed our lives of unhelpful beliefs. It’s painful sometimes, but it’s necessary. As Walter Kaufmann has written, “Undisciplined vision, unexamined intuition, and sheer passion are the fountainheads of madness, superstition, and fanaticism.”

There is a time to practice Paganism, and there is a time to talk about Paganism. There is a time to suspend disbelief, but there is also a time to suspend belief.

“ ‘All means all,’ she heard a voice in her mind whisper. ‘I proliferate, I don’t discriminate. But you have the knife. I spin a billion billion threads, now, cut some and weave with the rest.’ ” — Starhawk, The Fifth Sacred Thing

It is necessary from time to time to get out that knife and carve away at our experience. Not every experience is equally valuable. Not every interpretation of our experience is equally useful. Not every belief is worth holding on to. I agree with John Beckett when he wrote: “Distinctions matter – all [the] different ways of thinking about the Gods aren’t equally true or even equally helpful. ” We need to exercise discrimination. We need to do this as individuals. And we also need to do this as a community.

This is what much of this blog is about. Here, I use the language of logos to structure the experience of mythos. This is not where I practice Paganism. Here is where I write about Paganism. Internet Paganism is not Paganism.

It’s true that, unbalanced by mythos, logos has a tendency to kill the thing which is trying to describe. But it is also true that, unchecked by logos, mythos tends toward folly and inanity. It’s true that we can’t have religious experience while our rational minds are on high alert. But neither should we abandon rationality altogether. The trick is not to confuse one with the other … and not to try to do both at the same time.

As B.T. Newberg has suggested, I think we need to “Dive deep and let rationality be our lifeguard.” Religious naturalists, like myself, have a tendency to sit on the edge of the pool of religious experience and dangle our feet in the water, refusing to let go of the edge. As a result, we miss out on the full experience. On the other hand, there are those who jump in with both feet, but forget to return to the edge from time to time. We can’t have the experience of swimming in the waters of religious experience, until we let go of the side of the pool. On the other hand, we need to periodically return to dry land in order to analyze our experience — else we run the risk of drowning in a sea of superstition and fanaticism.