I recently suggested that we should pay much more attention to the Deuterocanonical books that are no longer found in most Protestant Bibles. Partly this is because of their artistic and cultural influence, but their religious significance is immense.

Two substantial “Second Canon” books in particular demand our attention, namely Wisdom (“the Wisdom of Solomon” and Sirach (Ecclesiasticus). Together with the canonical books of Proverbs and Ecclesiastes, they are major components of the once-vast wisdom literature of the ancient Jewish world, which reached its height in the last two centuries before the Christian era.

These books also help us understand the roots of Christian thought and belief. In the late second century, the Muratori Canon included “the Wisdom written by friends of Solomon in his honor” in the New Testament, alongside Jude and i and ii John. (Another possibility is that the term refers to Proverbs).

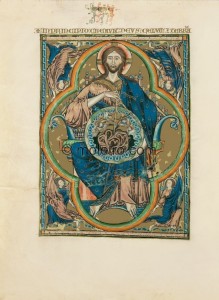

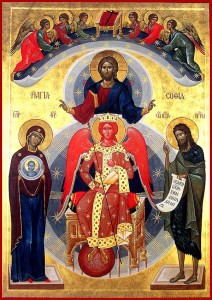

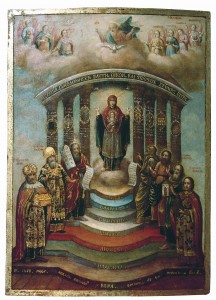

The various wisdom books all offer useful practical advice for living. Beyond this, though, they extol Wisdom itself, who is often personified, usually in female form (Greek, Sophia). Wisdom/Sophia even becomes a heavenly figure, the means of Creation, and to varying degrees, these books even associate Wisdom with God Himself.

Describing the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, James H. Charlesworth writes that we see concepts becoming “personified and eventually hypostatic. The earliest and best example of them is Wisdom, who can now be seen walking on earth. God’s word is seen first as the word of God, then the word from God, and finally, perhaps in only a very few circles, as ‘the Word’.”

Proverbs has Wisdom saying,

The Lord created me at the beginning of his work, the first of his acts of old.

Ages ago I was set up, at the first, before the beginning of the earth (8.22-23).

The Deuterocanonical books develop this theme. In Sirach, for instance, Wisdom declares that,

I came forth from the mouth of the Most High, and covered the earth like a mist.

I dwelt in high places, and my throne was in a pillar of cloud.

Alone I have made the circuit of the vault of heaven and have walked in the depths of the abyss.

In the waves of the sea, in the whole earth, and in every people and nation I have gotten a possession (24.3-6).

In the Book of Wisdom itself, we read:

For she is a breath of the power of God,

and a pure emanation of the glory of the Almighty;

therefore nothing defiled gains entrance into her.

For she is a reflection of eternal light,

a spotless mirror of the working of God,

and an image of his goodness (7.25-26)

In Chapter 11, we hear of Wisdom’s deeds in guiding and protecting all the figures of the Old Testament, from Adam onwards.

You can interpret the Wisdom figure in many ways, and Jews have often identified her with the pre-existent Torah. For Christians, though, it is difficult to read such passages without thinking of the exalted Christology that we find in the Gospel of John and elsewhere in the New Testament, particularly the idea of the Logos in John 1. So many of these Wisdom texts lend themselves to the support of Trinitarian doctrine. In fact, my own Episcopal Church used that passage from Proverbs 8 on Trinity Sunday, some weeks ago.

Jesus’s first followers may or may not have thought of him as some kind of manifestation of Wisdom. But in any case, that Wisdom idea certainly contributed mightily to the concept of Christ as Logos that would become the orthodoxy of the Great Church.

It’s sad, then, that the Protestant canon does not include two of the main texts that support such an important idea in the history of the faith.