The Egyptian abbot Shenoute is one of the major Christian figures of Late Antiquity. He never shied away from a fight, and often a literal physical confrontation. As a result, he has left a mixed historical reputation, and he is easily stereotyped as a crude and even thuggish figure. But the abundant evidence we find in his writings gives us a startlingly detailed picture of the world in which he lived, and its many dangers. It sometimes evokes the modern world of emerging Christianity, especially in other parts of the African continent.

Some years ago, Michael Gaddis published an excellent book entitled There Is No Crime for Those Who Have Christ: Religious Violence in the Christian Roman Empire. The main title is a remark made by Shenoute when he was raiding a pagan’s house in search of idols. As we know from multiple sources, the monks of Late Antiquity could be a ferocious and even lethal brood, and the Egyptian representatives were among the toughest. Shenoute made no apology about deploying them against pagans, who remained strong in Upper Egypt long after the Roman Empire formally became Christian.

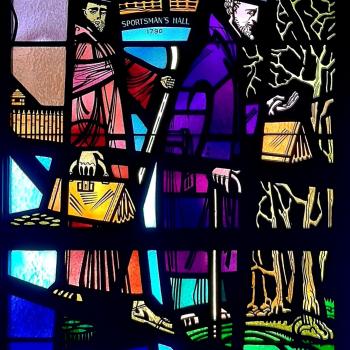

We see material signs of this struggle in the physical remains of many older Egyptian churches, which either annexed older temples, or else raided their structures for building materials. In the White Monastery itself, we find reused fragments of old temples, with hieroglyphics still intact. Historic preservation was of no concern to the monks!

Although it does not excuse the violence and intolerance, Shenoute’s ferocious hostility to pagans is easier to understand when set in a class perspective. Shenoute himself was the son of a peasant, and spent his youth as a shepherd. His deadliest enemies were the local pagan landowners, who he saw as vicious oppressors of the poor, and who needed urgently to be put in their proper place.

Also, he saw the temples not as centers of a rival world faith, but literally as the haunt of demons. Literally and spiritually, the landscape stood in need of conquest. (We might see parallels with contemporary Nigerian charismatic Christians, who believe their land is tainted by centuries of pagan worship and blood sacrifice).

Shenoute’s Egypt was also a very lively intellectual center, with many competing beliefs and ideologies, and the controversy between rival factions could become vicious. Under its successive patriarchs or popes (Theophilus, Cyril and Dioscuros), the Alexandrian church became a fortress of militant orthodoxy, determined to suppress all potential enemies. The murder of the philosopher Hypatia in 415 was a notorious milestone in these campaigns. When the Alexandrian leaders needed muscle to enforce their views, they turned to the monasteries, and especially to a monastic overlord like Shenoute, who deployed a sizable militia.

Best recorded are the struggles against two ancient but surviving currents of belief, particularly Origenism. The steps taken against it were savage, and repressive. In the 440s, Patriarch Dioscuros wrote to Shenoute about an Origenist monk, Elijah

who was a priest indeed for a time, but who was revealed as a destroyer of souls and on this account we degraded him; on this account we appointed and ordained that he should not be found, nor should he live from this time forth either in the diocese of Shmin [Panopolis] or in any other city of the Eparchy of the Thebais, or in the monasteries, or in the caves in the desert; we being anxious lest he should contaminate others so as to become zealots and partakers of his heresy or his evil teachings.

Shenoute was to assist in seizing any books teaching this heresy, to send them to Alexandria.

Shenoute lived at a time of warfare, physical as well as spiritual. He never doubted that he was called to be a warrior.

By the way, one informative book on these matters is Johannes Hahn, Stephen Emmel & Ulrich Gotter, eds., From Temple To Church: Destruction And Renewal Of Local Cultic Topography In Late Antiquity (Brill, 2008). See especially Stephen Emmel’s chapter, “Shenoute of Atripe and the Christian Destruction of Temples in Egypt.”