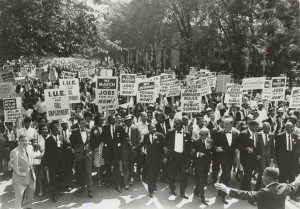

Last month, we celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the March on Washington. Led by veteran civil rights activists A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin, the event sought to provide a public demonstration of support for a comprehensive civil rights bill being proposed by President Kennedy. Most well-known for Martin Luther King, Jr.’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, the march aimed to galvanize existing backers of civil rights legislation even as it catalyzed others to support it. The public momentum it spawned contributed to the Johnson administration’s ability to pass both the Civil Rights Act (1964) and the Voting Rights Act (1965). The former prohibited discrimination in public space and employment decisions, whereas the latter buttressed the Fifteenth Amendment, targeting discriminatory voting practices. Together, they strengthened the ability of the Federal Government to provide greater protection for the rights of African American citizens while giving those same citizens greater legal standing to bring cases in Federal Court.

This month marks the fifty-sixth anniversary of the efforts of nine African American students to enroll at Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. “The Little Rock Nine,” as they were dubbed, had been carefully vetted to attend the previously all-white school in order to satisfy a federal order aimed at enforcing the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board (1954) . As the Little Rock school board complied with the federal government’s demands that it integrate its schools, many hoped that their high achievement and strong character would help smooth that process. Such hopes proved foolhardy. In the end, only President Eisenhower’s decision to deploy troops from the 101st Airborne Division made it possible for them to matriculate at Central High school in September 1957.

Five years later, after a winning protracted legal battle in Federal Appeals Court with the support of the Kennedy administration, James Meredith attempted to enroll at the University of Mississippi. Accompanied by Federal Marshals, rioting broke out on campus that left two people dead. Feeling compelled to act, President Kennedy federalized the Mississippi National Guard and deployed federal soldiers to the region. They successfully dispersed the rioters by employing tear gas and arresting hundreds. Afterwards, Meredith successfully enrolled at Ole Miss, earning a bachelor’s degree the next year.

A year later, in 1963, a similar scene recurred in neighboring Alabama. As Governor George Wallace carried through his promise to “stand in the schoolhouse door” in order to prevent integration at the University of Alabama (Tuscaloosa), federal marshals and Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach sought to help James Hood and Vivian Malone become the first African Americans to matriculate there. When President Kennedy once again federalized and deployed the national guard, Wallace retreated, allowing the pair to enroll. Malone would earn a bachelor’s degree from the school while Hood went on to complete his studies elsewhere.

Contemporary white evangelicals who are suspicious of the federal government and decry its expansiveness–often employing similar language–would do well to recall this recent history. For in the African American experience, in combination with their own persistent efforts, only the concerted efforts of a muscular federal government guaranteed the most fundamental rights accorded to them as citizens–rights that had been intentionally denied them by state and local authorities.

Resources and Further Reading:

Eagles, Charles W. The Price of Defiance: James Meredith and the Integration of Ole Miss. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2009.

Elliott, Debbie. “Integrating Ole Miss: A Transformative, Deadly Riot.” Morning Edition. NPR. October 1, 2012.

Goldstein, Richard. “James A. Hood, Student Who Challenged Segregation, Dies at 70.” Obituary. New York Times. Online Edition. January 20, 2013.

“Integrating Ole Miss: A Civil Rights Milestone.” John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Last accessed September 11, 2011. http://www.jfklibrary.org/JFK/JFK-in-History/Civil-Rights-Movement.aspx?p=2

“James Meredith Graduates from Mississippi.” Historic Headlines. New York Times, Online Edition.

Williams, Juan. Eyes on the Prize: America’s Civil Rights Years, 1954-1965. New York: Viking Penguin, 1987.