I have been thinking how warfare drives religious change.

This arises partly from preparing the graduate course I am teaching at Baylor University in the coming Spring semester on Global Christianity, where of course I am tracing the fates of different churches and missions over lengthy periods of time. Also, the new book I have coming out next year presents the case for the First World War as a worldwide religious revolution. This is The Great and Holy War, to be published by HarperOne in May 2014 – more on that in coming posts.

Whether in teaching or writing, I frequently note the contribution of wars to religious history, although I don’t think this point receives anything like the attention it deserves in standard histories of Christianity, or of other religions. The literature on “war and religion” is of course vast, but normally it refers to the ethical and spiritual dimensions of violence – when for instance can Christians support war? When is resistance necessary? What are the criteria for a just war? Historically, how have preachers or theologians justified war?

My theme is different. Major wars, of their nature, often provoke such massive and far-reaching changes that they deserve to be regarded as revolutionary movements in their own right, equivalent to the French or Russian Revolutions. Political consequences apart, they transform society, technology, the economy, and culture, and their effects can reverberate for decades. It is scarcely surprising then that time and again, we see wars affecting the shape that particular religions or religious traditions take.

Wars make or break religions, to a degree that might be uncomfortable for thinkers in traditions nervous about seeming to praise or endorse violence. A disciplinary bias might also be at work, in that historians of Christianity are not necessarily too familiar with political, imperial or military history. That’s a general observation, not a criticism.

Without wishing to offer anything so grand as a new theory of religious history (!), let me offer a few themes and thoughts.

*War has shaped the foundation of major religions

The obvious example here is the rise of Islam, which would not have achieved the worldwide impact it did without the military successes of the Arab armies. The political consequence of that movement ultimately destroyed what had been one of the world’s great world religions, namely Zoroastrianism, which today survives only on a tiny scale.

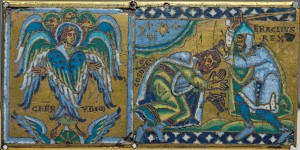

If military and imperial affairs had worked out differently – if for instance the Roman and Persian empires had not weakened each other so appallingly in their long wars between 530 and 630 or so – then conceivably the Islamic movement would have been strangled at birth.

Another example would be the great Jewish revolutionary war against Rome between 66 and 73AD, which led to the sack of Jerusalem and the Fall of the Temple. Among many other consequences, that catastrophe led to the complete restructuring of Judaism, essentially to the creation of what became medieval and modern Judaism; and also to the decisive split between Judaism and emerging Christianity.

Different outcome, different religious histories.

*The outcome of war decides which competing religions will grow and spread their influence

Wars determine the success or failure of states, and with them the religious traditions that they support. In some cases, failure in war can result in a religious current being utterly wiped out. (If you don’t believe that, just ask an Albigensian).

Suppose for instance we are tracing the early history of Protestantism. We might tell that story through a sequence of reformers and theologians, thinkers and preachers. Arguably, though, the most important event that happened in seventeenth century Protestantism was the outcome of the Thirty Years War, and specifically around the year 1630. If matters had worked out a little differently, the whole Protestant state order could easily have been smashed in Germany and Northern Europe, leaving only disfranchised minorities. Presumably, these would have been the targets of a lengthy Catholic reconversion campaign, on the lines of what actually happened in Bohemia and Austria in the later seventeenth century.

Although major Protestant powers were not directly involved in the war – notably England – their regimes would have faced enormous political and cultural pressures to conform to the new continental religious order.

Protestantism did not survive the seventeenth century because of the piety of individual believers, its theological sophistication, or its attitude to Bible translation. It survived because Protestant states somehow defeated their Catholic rivals on successive battlefields. Without Swedish and Dutch military successes in the 1630s, Protestantism would have been a footnote in Christian history.

Good old-fashioned power politics also proved decisive. Catholic France was “the eldest daughter of the church,” but had no wish to live in a Europe dominated by Catholic Habsburgs. France thus swung its military might against Catholic Spain and the Empire, in effect saving the Protestants.

*Imperial wars shape the success or failure of overseas missions

Less apocalyptically, we see how almost casual were the transitions of rule in particular European colonies overseas. In India, for instance, the wars of the 1750s could easily have created a French hegemony, driving out the English. In a hypothetical French Raj, Catholic missions would presumably have occupied the role that English Protestants actually played in “real” history.

In Africa likewise, the success or failure of imperial armies decided which particular states and their churches won the right to convert particular territories. Those missions might not have been enormously influential in their early years, but their efforts mattered enormously as Christianity boomed across the continent. Anglicans and Catholics won huge successes. If colonial wars had worked out differently, perhaps German Lutherans would have won those rich spoils. (Yes, I know Africa has its Lutherans, but their numbers could have been far larger).

Wars also disrupt the communication networks on which missions depend. The triumph of Christianity in modern black Africa owes much to the First World War years and the severing of traditional ties with mission agencies in metropolitan nations. This forced native African churches to develop their own leaders, and the following years witnessed a widespread upsurge of prophets and charismatic leaders. Many modern independent churches date from these years.

*The horrors of war stir mystical and even apocalyptic expectations, driving revivals and new religious movements.

I will discuss this in my next post.

Hmm, this material is starting to look like the sketch for a course, isn’t it? Or even a book?