Even in slaveholding states, many white Americans were uneasy about the morality of black slavery in the decades that preceded the Civil War. However, there were two things such Americans disliked far more than slavery: black people and abolitionists.

According to Luke Harlow’s recently published Religion, Race, and the Making of Confederate Kentucky, those double hatreds explain much about the trajectory of religion and politics in the Bluegrass State between 1830 and 1880. Although Kentucky’s antebellum white evangelicals were divided between those who favored gradual emancipation and those who supported the persistence of slavery, they were united in their opposition to abolitionism and in their support for white supremacy.

Having not seceded (and having only a small portion of its territory occupied by Confederate troops), Kentucky did not need to be “redeemed” from Republican rule like other southern states. Nevertheless, in their vigorous opposition to Republican Reconstruction, white evangelicals found a greater degree of unity after the war. “Racist religion,” Harlow explains, “…created cultural and political solidarity with the white South,” a solidarity undergirded by a theological consensus once partly obscured by pre-war political disagreements. “The [postwar] result,” Harlow concludes, “racist unity legitimated by postbellum clergy and laity who rejected civil rights for African Americans, embraced a Confederate memory of the war, and paved the way for the emergence of a dominant white Democratic political bloc in the state.” White Kentuckians embraced a cause lost by others and made it their own.

White evangelicals dominated Kentucky religion, as much as anywhere in the nation. By the end of the war, nearly all agreed that churches and ministers should eschew the political and focus on the spiritual. The spirituality of the church, however, meant the practical sanctification of white supremacy. “Conservative religion,” Harlow concludes pointedly, “made Confederate Kentucky.”

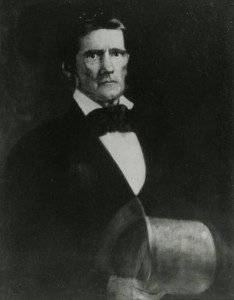

Harlow reaches those sober conclusions through careful research and portraits of white Kentucky evangelicals. His is a fascinating cast of characters. Baptists and Methodists were numerically dominant in Kentucky, but Presbyterians exercised tremendous public influence. And Robert J. Breckinridge (whose nephew John C. Breckinridge gained the support of southern Democrats in the 1860 presidential election) towered over most of his fellow Presbyterians. Breckinridge, politician-turned-minister and college president, was an antislavery slave owner. As that latter fact suggests, his antislavery was more theoretical than actual. During the Civil War, he tried — apparently without success to retrieve his slaves from a Union camp. Breckinridge favored gradual emancipation and the colonization of African Americans to Liberia. Like many technically antislavery whites, Breckinridge feared the presence of free black people far more than he disliked slavery. Thus, like a good number of other Americans, Breckinridge was an emancipationist who never emancipated.

Moreover, while Breckinridge disagreed with proslavery Kentuckians on the morality and wisdom of American slavery, he thoroughly agree with them on the dangers of abolitionism. Anti-abolitionism united nearly all white Kentuckians. It is important here to understand Harlow’s distinction between emancipationists and abolitionists. Some Kentuckians, like Breckinridge, supported the former. Nearly all vigorously opposed the latter. They considered abolitionists heretics because of their approach to the Bible and dangerous because they threatened white supremacy. Emancipationists and proslavery evangelicals were united theologically even if at political odds prior to the war.

Kentucky did have a few bold “heretics.” John G. Fee, the radically abolitionist Presbyterian founder of Berea College, did indeed read the Bible very differently. Like other Christian abolitionists, Fee favored scripture’s “spiritual intent over against its literal word.” Just because the Bible seemed to take the existence of slavery for granted did not mean that it could square with Jesus’s clear command to love one’s neighbor. “We need … a different kind of teaching,” insisted Fee. Berea’s founder’s racial egalitarianism was matched by very few white Americans. Whereas most whites fretted about the social implications of black freedom, Fee openly embraced “amalgamation”: “Better that we have black faces than bad hearts, and reap eventually the torments of hell. We may have pure hearts if our faces should, after the lapse of a century or two, be a little tawny.” Not surprisingly, his conservative opponents in Kentucky exiled him to Ohio. Gradual emancipationists like Breckinridge and openly proslavery evangelicals could fellowship with each other. Neither could stand the presence of abolitionists in their midst.

Harlow seems to agree with Mark Noll that most evangelicals could not break free of a biblical hermeneutic that led them to support slavery, at least in the abstract. Kentucky’s evangelicals believed that “a commonsensical, plain reading of the Bible revealed the Christian God’s sanction for slavery.” Some conservative white evangelicals believed that the Bible endorsed some systems of slavery but not that found in America. Most, however, felt that any sort of vigorous opposition to slavery struck at the biblical bedrock of their faith. And therefore they could not embrace true antislavery positions. Moderation, as preached by the gradual emancipationists, “was not benign, nor was it morally or politically neutral. Moderation was an ethical stance that sought every possible avenue to avoid confronting directly the most pressing dilemma of the nineteenth century.”

Harlow might have more clearly positioned himself vis-à-vis recent scholarship on evangelicalism, the Bible and slavery (he discusses books by Mark Noll, Eugene Genovese and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, Molly Oshatz, and Charles Irons). As Harlow notes, one could ask whether it was exactly a “faulty hermeneutic” that explains the failure of most white evangelicals to actively oppose slavery. Racism clearly “pervaded proslavery [and anti-abolitionism] Christianity.” One needed more than a “Reformed, literal hermeneutic” (Noll’s phrase) to presume that Genesis 9 sanctioned black slavery, for instance. Harlow also seems to think Noll too “sanguine about the possibilities of alternative hermeneutics to solve the Bible-and-slavery dilemma.” Of course, in Kentucky most white evangelicals simply saw no dilemma about slavery or white supremacy. One must at least conclude that the way that most white American evangelicals read the Bible did not lead them to oppose glaring social injustices. Instead, they tended to sanctify those injustices.

During the Civil War, a majority of white Kentuckians opposed secession. They were ultra-conservative Unionists, however, because they wanted the Union as it was, not as it became during the war. Thus, by the end of the war, Kentuckians opposed Republicanism (which they often labeled “Black Republicanism”) almost as vigorously as they opposed abolition. Robert Breckinridge, indeed, was somewhat unusual in that his Unionism was so fervent as to lead him to finally accept abolition. He had denounced the Emancipation Proclamation when promulgated, but Breckinridge remained a Lincoln supporter. That made the aging Presbyterian lion unusual. Nearly 70 percent of Kentucky voters cast their ballots for George McClellan in 1864. Once resolutely anti-abolitionists, white evangelicals in Kentucky now become fervently anti-Republican.

Despite Harlow’s careful focus on intra-Kentucky developments, he correctly asserts that his is an American story. For most of the early-to-mid nineteenth century, a majority of white Americans northerners considered abolitionism far more threatening than the slaveholding South to both Christianity and the Union. The Fugitive Slave Act, the repeal of the Missouri Compromise, the Dred Scott decision, and other developments of the 1850s eventually changed the minds of a good number of northern white evangelicals. But not all, and not for long. Within a few short years of the war’s conclusion, many northern white evangelicals joined their southern counterparts in opposition to Republican radicals.

Harlow’s book adds to a wealth of careful studies of the relationship between nineteenth-century evangelicalism and slavery. It is a significant virtue of Race, Religion, and the Making of Confederate Kentucky that he persists with his narrative beyond the war’s end into the Reconstruction years. Sadly, one could probably continue in that vein from Reconstruction through the years of the Civil Rights Movement and beyond.