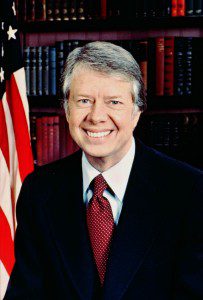

In 1976, a man named Jimmy Carter became the Democratic Party nominee for President. A Southern Baptist, he also called himself an “evangelical” and claimed a “born again” experience. “Who were these evangelicals,” a provincially-secular group of reporters and political operatives asked, “and how many are there?” Extensive polling followed, revealing that “evangelicals” comprised a substantial chunk of the American electorate. They adhered to a conservative Protestantism common in the nineteenth century and were numerous in the south, but neglected electoral politics. But recent social permissiveness and unrest in the 1960s had changed this. They now saw cultural engagement as their religious duty.

This is the basic story we all have heard. But if you’ve been reading my series, you will know it is at odds with the story I have laid out. So how does my argument for a market-driven faith, modern not traditional, relate to this competing narrative? In other words, how does “evangelicalism” as I have defined it (a historically-defined movement of individualistically-oriented Protestants) relate to the “evangelicals” referenced by most pollsters and reporters today?

Although there is overlap, the “evangelical” of pundits has a separate history, and an ephemeral meaning. Its history begins not with fundamentalists or neo-evangelicals, but with marketers.

***

In postwar America, historian Liz Cohen recounts, citizenship and politics began to be understood through the categories of consumption. Nixon’s famous “kitchen debate” with Nikita Khrushchev was emblematic; it focused on consumer goods rather than ideological, military, or diplomatic superiority. This shift also occurred at the grassroots. Consider how many iconic events of the Civil Rights movement were centered on consumption—whether at lunch counters or on busses. Equally important, politicos reimagined voters as consumers, appealing to them through television advertisements, while the candidate became a celebrity.

Political and consumer cultures were drawn even closer by the revolutionary shift to segmented marketing. During the first part of the twentieth century, American advertisers chased a mass market for their clients, hawking consumer goods to a “mass” whose tastes invariably reflected the white middle-classes. But in the 1960s, marketers began targeting smaller, previously ignored groups, with ads appealing to different tastes. They began with African Americans and various ethnic groups. But marketers quickly realized that they could use these techniques to create new market segments. According to Thomas Frank, they discovered a way “to call group identities into existence where before there had been nothing but inchoate feelings and common responses to pollsters’ questions.”

To be clear, market segmentation was a shift in marketing more than anything—it sold the same carbonated sugar water and frozen croissant dough. Their goal, as always, was a deeper penetration of mass-produced goods into unsaturated markets. But this was precisely what made segmented marketing so applicable to a two-party political system: it was the same two parties with different marketing strategies. Already consuming citizens, it was a short hop to interest group voting. And these political operatives also realized that they too could move beyond feminists and farmers; they could use demographics and psychoanalytic techniques to create their own segments. The end result of these techniques was “Soccer Moms,” “Nascar Dads,” and, yes, “evangelicals.”

This was the “evangelical” invented and used by pundits: a market segment. “Evangelicals” in this sense were not an untapped segment of voters that pollsters discovered, it was one they created. (Robert Wuthnow’s recent book on this topic is essential reading.) Granted, this creation was not out of whole cloth. Thanks to existing the evangelical networks I talked about earlier, there was a small, but solid, core of Protestants who already claimed the label. But this group never managed to define their essential beliefs. To be evangelical was an orientation—a pattern of thinking that shaped a person’s basic operating assumptions about religion.

And herein lay the rub: for the pollsters defining this evangelicalism needed to quantify it. They needed a question or two to put on a survey—preferably with limited responses to keep costs down. Orientations may create clearly identifiable patterns of belief, but they do not quantify well. (It’s like trying to quantify a language. Do you list every word and every grammatical rule and exception?) Add to this the fact that both Gallup Jr. and George Barna, the other major religion pollster, were both involved in evangelical networks (as I define it) and shared in its quantifying tendencies.

The result of all this? Pollsters relied on quantifiable bits of information that were only tangentially related to an “evangelical” orientation. And worse, the way it was defined has varied widely across surveys. Sometimes “evangelicals” are defined by doctrines (and this set regularly changes); other times respondents are asked to self-identify (often in distinction to “mainline” or “Catholic”). Most dubious are definitions based on membership in particular denominations that pollsters have deemed “evangelical.” Since a core conviction of historically-defined evangelicalism is that denominations do not matter, it’s hard to think of a less salient feature.

In any case, as Wuthnow recounts, the number of evangelicals instantly swelled from the NAE’s estimated two million to nearly 50 million. This was a larger bloc than American Catholics and was, by Gallop Jr’s estimation, a “built-in power base.” But this “evangelicalism” was not an organic movement; it was a conjured segment. Churchly conservatives might have selected the same predetermined theological answer as an evangelical, but that did not mean they saw the world in the same way, or considered the same thing essential, or consumed the same religious products.

Theological definitions of evangelicals also flattened the real social differences between white evangelicalism and other groups—principally African Americans and groups originating in Latin America and Asia. And it flattened the distinctive characteristics of corporate, Pentecostal, and politically-oriented evangelicals that divided the movement, leaving only “evangelical.” But since it supposedly represented a huge chunk of the electorate, that empty referent had immense power.

Who would speak for this new political movement? The most logical figure was Billy Graham, but after Watergate, he had grown reticent about speaking too directly on political issues. He found greater influence by staying above the fray, influencing Republican and Democratic presidents alike as America’s pastor.

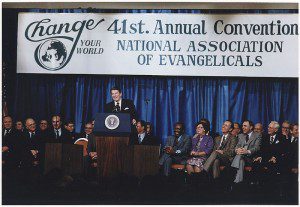

A litany of other individuals and organizations would try to fill this role over the years, but initially at least, the primary voice for the ephemeral evangelical segment was Ronald Reagan. It was he, in any case, that created peace among the three segments of historically-defined evangelicalism. Reagan’s message addressed all three groups simultaneously. His sunny optimistic faith in free markets spoke directly to corporate evangelicals. His promises to protect Americans from federal government encroachment and the Soviet Union spoke to politically-oriented evangelicals (while his massive military build-up financially benefited the many of these evangelicals working in the Sunbelt defense industry). And many Pentecostals were drawn to Reagan’s magical thinking—his supply-side economics (the belief that supply creates its own demand), his promises that policies benefitting the wealthy trickledown to the benefit of all, and that tax cuts solved every budget woe. These simply-implemented, win-win solutions happily made zero-sum games a thing of the past. Don’t fight for a bigger piece of the economic pie as the crusty Marxists told you, just grow the pie and everyone gets more. Just believe!

All three groups of evangelicals also rallied around Reagan’s moral reform—opposition to abortion. It highlighted the importance of every person, born or unborn, and thus the individualism so central to an evangelical orientation. (Catholics too would rally to the cause, but according to a different ethic of life.)

By speaking to all evangelicals, Reagan could thereby speak for them; and as they heard that message, they adopted it as their own—as if they had always believed. This was then reflected back into the media by “evangelical leaders”—individuals like Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson and, Jim Dobson—and organizations like the Moral Majority, the Family Research Council, the NAE or Christianity Today. All of these “leaders” were drawn from historically-defined evangelical networks. Since they reputedly spoke on behalf of the millions of “evangelical” voters captured in the polls, they exercised an outsized influence. The evangelical segment learned what they believed collectively from evangelical leaders, politicians, and pollsters. And they learned it well.

We can continue this story past Reagan. There was the disappointment of George H. W. Bush. His broken promise not to raise taxes was evidence that he was untrustworthy. He had sold out those he was supposed to protect, and demonstrated himself to be a political impostor rather than a true believer in free markets. In effect, he alienated all branches of historically-defined evangelicalism. The perception that evangelicals stayed home in 1992 (true or not) enhanced their reputation as a force to be reckoned with.

Evangelical influence reached its apex with the nomination of George W. Bush. Like Reagan, he also spoke for “evangelicals,” perhaps even more so. Bush could claim a sincere evangelical conversion with a demonstrable change in his life. He appointed a Pentecostal attorney general, pushed through a massive tax cut, and made faith-based initiatives a key policy initiative. Then the terrorist attacks and his shift to the protector-in-chief—even as he called on Americans to go shopping as a patriotic duty.

But in 2008, the housing crisis laid bare the reality of Reagan’s economic policies (that were largely continued by Bill Clinton and other centrist, “third-way,” Democrats in the 1990s). A shrinking middle class followed, along with stagnating wages, tightening credit, growing concentration of wealth, and evidence that the financial elites most responsible for the crisis would not be held to account. Corporate evangelicals remained true believers in free markets, but the populism intrinsic to politically-oriented evangelicalism reemerged with a vengeance. Thus, the illusion of a unified evangelical bloc held when times were flush, but it would not last the financial crisis. As each wing of the historically-defined evangelical movement returned to old patterns, tensions grew between them. Today the unwieldy coalition is disintegrating before our eyes. What began with Sarah Palin ultimately begat Donald Trump.

In this primary season, corporate evangelicals (the educated minority) rallied primarily around Rubio. Today they fill the ranks of #NeverTrump. Politically-oriented evangelicals rallied around Tea Party favorite Ted Cruz, drawn by his rhetoric of “Christian America” and his stubborn refusal to compromise. Most migrated to supporting Trump (some more willingly, some less) because…Hillary and the need for protection. They could stomach an unbeliever because God used Babylonian and Persian kings. But Trump’s first and most faithful supporters were Pentecostals—especially those from the “Prosperity Gospel” wing. They were drawn by his charisma, his decisiveness, his calling of things into being by a mere word (Trump Tower! Trump Steaks!), his aesthetic, and of course his wealth—a clear sign of God’s blessing.

Polls of “evangelical” support for Trump vary, sometimes wildly—again confirming Wuthnow’s thesis. But all show staggeringly high majorities of the evangelical voting bloc (however defined…however imperfectly) will be voting for Trump. This is confirmed by the litany of politically-oriented evangelical leaders strongly supporting him. This, I think, signals the end of the influence of evangelicals in Republican Party politics. Or at least it should if party officials take notice. For however they explain this mess, it will be difficult to justify their continued relevance.

Why are so many evangelicals voting for Trump? One explanation is that, despite his clear shortcomings, evangelicals are the most reliable Republican voters. But in politics, unthinking brand loyalty reaps no rewards; politicians are free to ignore them since their vote is guaranteed.

Perhaps evangelicals are voting for Trump because, despite his past pro-choice position, he now promises to appoint Supreme Court justices opposed to abortion. Abortion is just too important to vote otherwise, they say. If this is the case, then literally anyone can pass the anti-abortion litmus test by invoking the right incantation on the eve of running for office. There’s no need to do anything else nor pay mind to other evangelical concerns.

Or perhaps the explanation lies in the principled route, favored by most corporate evangelicals. Using various theological tests and measures of church attendance, they argue that most Trump voters are not “real” evangelicals. But if this is the case, then they have made evangelicalism so small that it no longer matters; they are a minority of a minority, like Log Cabin Republicans. In any case, these respectable evangelical “leaders” have demonstrated no influence over their supposed followers. What good is an intractable voting bloc?

I’m neither a fortune teller, nor a political scientist. And smarter historians have suggested evangelical political influence will continue. A Trump win, however unlikely, also may change the dynamics. But from my vantage point, it is hard to see the status quo of evangelical influence persisting much longer. A big Trump loss next Tuesday will confirm to Republican leadership that evangelicals have become a liability; for they are the reason that Trump became the nominee. They again pulled the party into untenable radical territory during the primaries. Republican elites may try to restructure the party to diminish grassroots evangelical influence. Perhaps we may see a shift toward the center. (Most progressives agree that if Hillary Clinton were anyone other than “Hillary Clinton” she’d make a pretty good Republican.) What political operatives and pollsters have created, they can also dissolve.

Thus, the 2016 election might end the politically-influential, poll-defined evangelicalism ascendant since Reagan. But I think evangelicalism as a historically-defined movement (and certainly as a religious orientation) is here to stay—at least until there is a radical shift in American political economy or some other disruptive transformation. But evangelicalism will, I think, undergo a dramatic recalibration. What that new evangelical landscape might look like, I’ll explore next time.