Jane Dawson begins and ends her biography of John Knox with touching, familial scenes.

The first is the 1557 baptism of Knox’s son Nathaniel in Geneva. Dawson writes that “Knox was standing beneath the pulpit proudly cradling his newborn son in his arms.” Knox stood next to his ministerial friend William Whittingham. A second friend, Christopher Goodman, baptized the baby. Knox, Whittingham, and Goodman had all helped write the service of baptism used that Sunday, part of a Forme of Prayer intended to strictly follow biblical strictures. The English-speaking congregation in Geneva was a “self-selected group of exiles from religious persecution,” a community closely knit together as part of the mystical body of Christ. Dawson presumes that Knox wept during the baptism, a reasonable speculation given his tendency toward tears.

Dawson ends her biography with another touching scene: Knox’s “good death.” Knox had prearranged for his secretary Richard Bannatyne to ask him during his last moments to signal that he held firm to the faith. During his final week, he hosted dinners with friends, telling them to drink all the wine because he would not be around to finish it. He summoned his entire congregation to hear a final message. His wife Margaret read passages of scripture to him a few hours before he died. And, when Bannatyne asked him if he remembered Christ’s promises, he “raised his hand for the last time.”

Dawson explains that Knox’s infamous The First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women “has given rise to the view that Knox was a misogynist or a woman-hater and has distorted understandings” of his political thought and preaching. She intends for the baptismal and deathbed scenes to provide a corrective to such views. Knox possessed “many different shades” within his complex character.

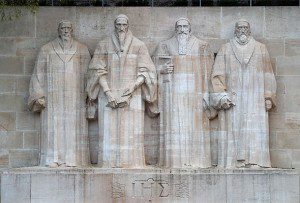

Knox is on the far right, next to William Farel, John Calvin, and Theodore Beza.

Dawson’s corrective partly succeeds. Knox did not hate all women, but he hated certain women with a vengeance. And he loathed a very large number of men as well.

Before addressing those hatreds, though, Dawson addresses Knox’s much-discussed relationship with his mother-in-law Elizabeth Bowes. Knox wrote long pastoral letters to Elizabeth, a recent and zealous convert to the Protestant cause. In one such letter, Knox referred to himself as “standing at the cupbourd in Anwik [the town of Alnwick]: in verie deid I thought no creature had bene temptit as I was.” Knox’s letters sparked gossip, to the point that Knox felt compelled to declare after Elizabeth’s death that he was familiar with Elizabeth Bowes not because of “fleshe nor bloode, but a troubled conscience upon hir part.” Her temptations were spiritual, not physical. So were his.

Dawson’s judgments seem sound. The “cupboard” was not a private closet, but a rather public dresser. She allows that Knox’s relationship with Elizabeth Bowes “produced a range of subtle interplays but probably not a relationship that was ‘sexual in the normal sense.”

Dawson also discusses Knox’s friendship with the poet and translator Anne Locke, whose work he helped publish.

On to the hatreds. The First Blast of the Trumpet proved one of Knox’s most impolitic actions in a very impolitic life. “This trumpet call,” Dawson writes, “blew away many friends.” It did not blow away Calvin, but Knox had specifically rejected Calvin’s own caution on the subject (the Genevan reformer pointed to the Old Testament example of women such as Huldah and Deborah). Knox argued that female rule was “repugnant to Nature; contumelie to God, a thing most contrarious to his reveled will and approved ordinance; and finallie, it is the subversion of good Order, of all equitie and justice.” Whew. Knox based his argument on everything from the Bible to Aristotle’s theories about female inferiority. He concluded that “women may and ought to be deposed from authority.” Naturally, Dawson explains, this was “political dynamite.”

Knox’s timing was as poor as his words were incendiary. Mary Tudor died shortly after Knox published his tract, and her Protestant successor Elizabeth wanted nothing to do with a preacher who encouraged the overthrow of queens. Knox intended to minister both in his native Scotland and in his adopted England, where he had taken refuge from Scottish persecution during the reign of Edward. Now he could not set foot in England. Moreover, Dawson explains, Elizabeth presumed “that everything to do with Geneva … was tainted by association with Knox’s views.”

Knox returned to Scotland, but female rule followed closely at his heels. Mary Stuart returned to Scotland as queen after the 1560 death of her husband, King Francis II of France. Knox made some efforts to get along, restraining himself somewhat in several audiences with the queen. Still, he was convinced that Mary Queen of Scots would prove just as bloody as Elizabeth’s successor. And in the many twists and turns of Scottish politics over the next decade, Knox could not help but taking sides and denouncing — defaming, in many cases — his opponents. When Mary was imprisoned in England, Knox openly called for the death of “that most wicked woman.”

Thus, in the end, despite Dawson’s successful efforts to humanize the Scottish reformer, readers will come away with a rather dour sense of John Knox. Over the final chapters of John Knox, Dawson emphasizes his “increasing intransigence, bouts of depression and gloomy predictions about the future of Protestantism.” For Knox, the world was divided between Christ and Antichrist. “In religioun thair is na middis,” he once wrote, “either it is the religion of God … or els it is the religion of the Divill.”

In the end, what humanizes Knox for me is not the baptism, the marriages, or the deathbed scene. Instead, Knox’s intransigence and vituperation make sense in the context of his life. Knox endured some rather terrible things. His mentor George Wishart was burnt at the stake. Then Knox was captured when French trooped captured St. Andrews. He was a slave on a French galley, then an exile in England, then an exile in Frankfurt and Geneva. While Knox saw the Protestant reformation succeed in Scotland, its future was tenuous for the remainder of his life. Not long before his death, he learned of the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. Certainly, other Scottish Protestants lived through similar circumstances and were nevertheless a bit more forgiving and charitable. For Knox, though, Protestantism was always an embattled international cause, and Knox was determined to not shun the battle.

Dawson’s biography is masterful. She introduces considerable new material from the papers of Christopher Goodman, including six previously known letters by Knox. Also, as illustrated by the above quotations, she makes generous use of Knox’s unedited words. Curious readers are unlikely to find a better introduction to Knox and the Scottish Reformation.