Over the weekend I gave the keynote address for the annual Honors Symposium at Crown College, a Christian and Missionary Alliance school west of Minneapolis. (Thanks to Michial Farmer for inviting me to speak!) Here’s a slightly abridged version of my remarks.

There are many ways we could talk about the importance of the liberal arts in a Christian setting like this. I should probably share statistics on salary and employment, or quotations about citizenship and civic virtue. But the most liberal artsy way to explain the liberal arts is to give you a metaphor: the liberal arts as a set of journeys — conveyed via examples from history, poetry, art, philosophy, and Scripture.

In particular, I want to reflect on Matthew 2:1-12. I’ll grant you that April is a weird time of year to talk about the Three Wise Men, but bear with me. See I’ve been chewing on something since January.

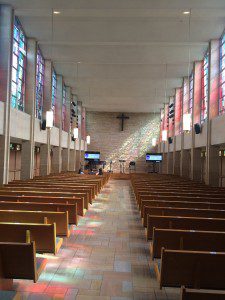

I was in London, England, a couple days into a three-week travel course on World War I. It was Friday night, and somehow I managed to talk two of our students into joining me at St Martin-in-the-Fields, a beautiful old Anglican church by Trafalgar Square. We’d come to celebrate Epiphany, the beginning of the Christian season that follows Christmas, the weeks when we reflect on how Jesus Christ was revealed as God-with-Us — first, to three mysterious wise men, or Magi, from the East.

The tradition at St Martin’s is that the Epiphany homily is broken into three parts, with hymns, poetry, and choral music in between. This year, the preacher (Alastair McKay) reflected on the three journeys of the Magi, as reported in Matthew 2.

As I listened to Revd McKay, it struck me that the three journeys he was narrating were journeys I’d taken, journeys that will be taken by anyone who opens themselves to the transformative power of the educational model known as the Christian liberal arts.

First, we journey to Jerusalem

In the time of King Herod, after Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea, wise men from the East came to Jerusalem, asking, “Where is the child who has been born king of the Jews? For we observed his star at its rising, and have come to pay him homage.” When King Herod heard this, he was frightened, and all Jerusalem with him… (Mt 2:1-3, NRSV)

Like the Queen of Sheba and Alexander the Great before them, the Magi come from outside the story of Israel to visit the city of David. They leave the part of the world where the Jews once lived in exile, forced to sing songs of Jerusalem, and come to Zion.

It’s no small thing to take this journey. When T.S. Eliot told his version of the “Journey of the Magi,” he began by cribbing five bleak lines from the 17th century Anglican bishop Lancelot Andrewes:

“A cold coming we had of it,

Just the worst time of the year

For a journey, and such a long journey:

The ways deep and the weather sharp,

The very dead of winter.”

But even as they dream in their weariness of “summer palaces on slopes… / And the silken girls bringing sherbet,” Eliot’s Magi continue on. For this is a journey of anticipation and commitment; this journey is a pilgrimage.

I don’t know how many of you will ever go to Jerusalem itself. (I haven’t.) But in our own ways, we all set out for a Jerusalem — we all of us set our hearts on a place that embodies our loftiest aspirations and most impossible imaginings. Whatever hard work, suffering, or sacrifice is required, we’ll do it in order to get to this Jerusalem.

For some of you, that’s the journey that brought you to this campus. You might be the first person in your family to go to college. Crown might have been your dream years before you sent in your application. At the very least, you saw it as opening a door to the freedom of adulthood, and letting you take the first step on your path to a profession or a marriage.

And I hope whatever it cost you to come here has been worth it. I do.

But ultimately, the journey to Jerusalem is both a journey of anticipation and a journey of disappointment.

The Magi come to a holy mountain where religion and politics fuse in unholy ways. They come to the city that Jesus laments: “…kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to it” (Matt 23:37). Rather than finding the true king, the Magi arrive in the court of a conniving tyrant who rules at the mercy of his Roman overlords. In search of power and justice, they find weakness masquerading as might. Solomon once sang of a king who would ”defend the cause of the poor of the people, give deliverance to the needy, and crush the oppressor” (Ps 72:4), but Herod is willing to commit mass murder in order to keep that Lord from taking his throne.

Likewise, the first journey of the Christian liberal arts is a journey of disenchantment. You will find — or have already — that this college, like Bethel and every other institution associated with Christ’s church, falls short. You will find — or already have — that this country has not always used power well, that it has betrayed its ideals as often as it has fulfilled them, that its leaders bear at least a passing resemblance to Herod and his masters.

Harder yet, even if you can do what Socrates thought difficult and convince others that the unexamined life is not worth living, you’ll find that the examined life is hard to endure, that there are aspects of your own life that don’t stand up to such scrutiny. If I’ve learned nothing else from my studies, it’s that history holds up a mirror to our own lives: and the reflection we see is uglier than we’d wish it to be.

At Bethel we often say that the liberal arts are liberating arts. Which is lovely — but liberation is painful. Bethel’s longest-serving president, Carl Lundquist, said that such studies free us from “the chains of ignorance, provincialism, bigotry and narrowness.” But part of us prefers those chains; they can seem safe and comfortable when you’re being confronted with the vast array of blind spots, false assumptions, and misplaced priorities that come into focus as we study the liberal arts. Just as the Israelites begged to go back into slavery rather than enter the wilderness of their exodus, we’ll be tempted to abandon this journey and retreat to ignorance, provincialism, bigotry, and narrowness.

Indeed, Eliot’s Magi are nearly disillusioned by the experience:

A hard time we had of it.

At the end we preferred to travel all night,

Sleeping in snatches,

With the voices singing in our ears, saying

That this was all folly.

Similar voices may have echoed in your ears, shouting that it’s folly to spend four years following this star. That this kind of study doesn’t lead to a job, or at least one that won’t pay off your loans, that it distracts you from the Gospel and seduces you to the ways of the world.

But the three wise men did not turn back. Weary and disenchanted as they were, they continued. And so should you, for there is a second journey.

Second, we journey to Bethlehem

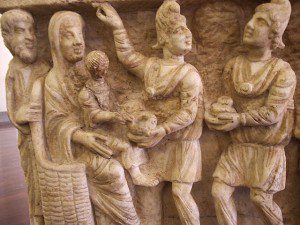

Then Herod secretly called for the wise men and learned from them the exact time when the star had appeared. Then he sent them to Bethlehem, saying, “Go and search diligently for the child; and when you have found him, bring me word so that I may also go and pay him homage.” When they had heard the king, they set out; and there, ahead of them, went the star that they had seen at its rising, until it stopped over the place where the child was. When they saw that the star had stopped, they were overwhelmed with joy. On entering the house, they saw the child with Mary his mother; and they knelt down and paid him homage. Then, opening their treasure chests, they offered him gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. (Matt 2:8-11)

Bethlehem may have been the city of David, but it was no great metropolis. Few people of the ancient world set their hearts on visiting a town that, according to the prophet Micah, was “one of the little clans of Judah” (Mic 5:2). And yet that’s where the star guides the Magi. They are led not to a palace in Jerusalem but a nondescript house in Bethlehem; they do not find a king and his court, but a child, his peasant mother, and carpenter father.

And they are “overwhelmed with joy.” They fall to their knees in worship and give him the best gifts they can offer.

And so shall we all. For this is their second journey: an unexpected, unplanned trip in which they finally found what they’d been looking for the whole time, in the least likely place.

What is your Bethlehem, asked Revd McKay? Where — to your complete surprise — will you encounter Jesus Christ?

This is the second journey of the Christian liberal arts as well. Having disenchanted and disillusioned you, these studies now bring you to the unexpected joy of knowing Jesus Christ. Having seen the world more clearly, you now glimpse the light that no darkness can overcome.

Consider an unlikely example as I go back to that travel course to Europe, where we study a world war that took fifteen million lives and set the stage for a sequel that took four times as many — including 6 million Jewish lives in the Holocaust. We talk about faith, but as we move on from London to the Western Front and end in Munich and Dachau, we mostly we talk about how and why humans kill humans, how that killing is mourned and remembered, and how it reshapes everything from literature to manufacturing, technological innovation to artistic styles.

If you study that history, you’ll see crosses everywhere, at memorial after memorial and cemetery after cemetery. But you’ll also see the people who make up the Body of Christ being crucified. For example, I’ll never forget coming to Charles Sargeant Jagger’s relief “No Man’s Land” in the Tate Britain gallery, seeing a dead soldier with outstretched arms entangled in barbed wire, and immediately being brought back to the gruesome sight of Christ crucified in The Isenheim Altarpiece.

Worse yet, you’ll see members of that same Body crucifying others. As when you enter the Catholic Chapel of the Mortal Agony of Christ at Dachau and think of all those killed in the Holocaust by supposed followers of Jesus.

Sometimes you see an image of God rendered as negative space because his absence is so painfully obvious, and you’re reminded that his inspired scripture include bitter words of unrestrained lament:

I am one who has seen affliction

under the rod of God’s wrath;

he has driven and brought me

into darkness without any light;

against me alone he turns his hand,

again and again, all day long. (Lam 3:1-3)

But then you see the sun dawning over five thousand graves on the Somme and your heart wants to sing with Zechariah:

By the tender mercy of our God,

the dawn from on high will break upon us,

to give light to those who sit in darkness and in the shadow of death,

to guide our feet into the way of peace. (Luke 1:78-79)

You see London’s Cenotaph, are told that its name is from the Greek for “empty tomb,” and find yourself with the women that first Easter. You think of resurrection and remember that even the author of Lamentations, with his soul “bowed down within me,” knew that the “steadfast love of the Lord never ceases, his mercies never come to an end” (Lam 3:21, 22).

I often tell my students that the most important objective in any course I teach is not listed on the syllabus. It can’t be, for I can’t plan it (or assess it). Not the acquisition of knowledge or the cultivation of research, critical thinking, or writing skills — above all else, my goal is that my students will encounter Jesus Christ.

And that encounter will leave them changed. Their studies will be part of their ongoing conversion, as they turn towards the one in whom “we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28) and grow to be more like him.

That’s what we mean when we promise prospective students a transformative education, when we quote the apostle Paul and tell students that the best defense against being “conformed to this world” is the “renewing of your minds” (Rom 12:2). We mean that they will take a journey to Bethlehem and find Christ.

What we don’t emphasize enough is that such an encounter is costly (not just in a financial sense), or that such change can be frightening. This journey is like the quest of The Hobbit. At least as the film version begins, a nervous Bilbo Baggins asks the wizard Gandalf, “Can you promise that I will come back?” “No,” replies Gandalf. “And if you do, you will not be the same.”

As T.S. Eliot’s poem finishes, the last of his Magi asks what their journey was all for:

…were we led all that way for

Birth or Death? There was a Birth, certainly,

We had evidence and no doubt. I had seen birth and death,

But had thought they were different; this Birth was

Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death.

Indeed, the journey to Bethlehem is an encounter with new life — but the Magi must know that death is not so far away, for one of their gifts is myrrh, used in the ancient world to embalm corpses.

It’s a hard word to hear. Few of us come to college and take an American lit or Asian history course in order to die. But if what we’re doing is a kind of conversion to a Christ who was both crucified and resurrected, then we should expect that life comes from death. As Paul wrote earlier in Romans: “Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? Therefore we have been buried with him by baptism into death, so that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, so we too might walk in newness of life” (Rom 6:3-4).

At the end of his quest, Bilbo is not the same… but he does survive and come back to the Shire. And that takes us to our final journey.

Third, we journey home

This is the part of the story that Matthew is least interested in — or knows the least about. He dismisses the Magi from his gospel with a single verse: “And having been warned in a dream not to return to Herod, they left for their own country by another road” (Mt 2:12).

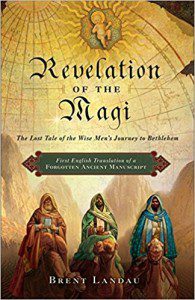

That’s it. We don’t know how that journey went, or even which country was their own; we don’t know what they reported of their time in Judea, or how it was received. All we can do is speculate — and people have. A work of early Christian apocrypha known as the Revelation of the Magi says that the star carries them back to their mythical homeland of Shir, where Christ appears to the people — preparing the way, years later, for the Apostle Thomas to evangelize them on his journey towards India.

That’s it. We don’t know how that journey went, or even which country was their own; we don’t know what they reported of their time in Judea, or how it was received. All we can do is speculate — and people have. A work of early Christian apocrypha known as the Revelation of the Magi says that the star carries them back to their mythical homeland of Shir, where Christ appears to the people — preparing the way, years later, for the Apostle Thomas to evangelize them on his journey towards India.

We don’t know that. But Matthew’s few words do tell us three important things. First, the Magi didn’t go back to Jerusalem — having been disenchanted, they knew better. Second, they didn’t stay in Bethlehem, tempting as it must have been to remain in the presence of Emmanuel. (Who wouldn’t want to remain “overwhelmed by joy”?) Instead, they left; wherever home was, they went there.

Except that it can’t have felt quite like home. Here’s how Eliot speculates:

We returned to our places, these Kingdoms,

But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation,

With an alien people clutching their gods.

I should be glad of another death.

And your education will end in a similar fashion. You won’t go back to whatever was your Jerusalem: you know better. But you won’t stay in the Bethlehem of your education, tempting as it will be to keep paying Crown tuition. And while you might live in your parents’ basement for a time… You can’t really go home again. You will go out knowing better than you ever have that you are a “peculiar people” (1 Pet 2:9, KJV), sent out into the world as “ambassadors for Christ” (2 Cor 5:20).

But the key is that you do go out. The key is that you give God the same answer as the prophet Isaiah: “Here am I; send me!” (Isa 6:8).

But where? In which direction? There’s no map for this journey, no signpost, no GPS… There’s only a voice, calling you to him and sending you out in his name.

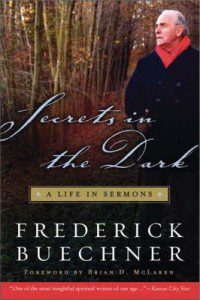

Unfortunately, as the Presbyterian pastor and novelist Frederick Buechner said once, while preaching on Isaiah 6, “our lives are full of all sorts of voices calling us in all sorts of directions. Some of them are voices from inside and some of them are voices from outside. The more alive and alert we are, the more clamorous our lives are. Which do we listen to? What kind of voice do we listen for?”

You are being sent out into a noisy world, “where there are so many voices and they all in their ways sound so promising.” None is louder than “the great blaring, boring, banal voice of our mass culture, which threatens to deafen us all by blasting forth that the only thing that really matters about your work is how much it will get you in the way of salary and status…”

But this is your chance. Before you’re encumbered by too many responsibilities and obligations, think about your education as a relatively quiet space in which you have the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to tune your ears to hear God’s voice — in Scripture and theology, but also in the cadences of poetry and music, in the narratives of history and theatre, in the song of birds and bubbling of test tubes, in the cries of those who suffer.

If Buechner is right, then the sound of God’s call on your life is actually like a vocal duet: the sound of two different voices singing two different notes with two different timbres — and one ultimate purpose.

First, we should go “[w]here we most need to go,” follow “the voice of our own gladness,” and do that which “leaves us with the strongest sense of sailing true north and of peace, which is much of what gladness is…”

Second, we should go “where we are most needed,” into a world with “so much drudgery, so much grief, so much emptiness and fear and pain,” and offer ourselves in service.

And if, Buechner concludes, you answer to those two voices, you will take up “the calling of all of us, the calling to be Christs.”

What does this have to do with the Christian liberal arts? Buechner advises us to “keep our lives open,” but it’s hard to do that if you track yourself into a professional path admitting little personal exploration. As it happens, the broad study of the liberal arts both helps you know yourself more deeply, so that you’re better able to discern that “true north” that is specific to you, and in disenchanting you, it helps you recognize the grief and pain that you can alleviate, the emptiness that you can fill.

“With the drawing of this Love and the voice of this Calling,” wrote T.S. Eliot in another, more famous of his poems, “We shall not cease from exploration…” Of course, that’s from the conclusion to “Little Gidding,” the last of Eliot’s Four Quartets, which happened to be the conclusion of the Epiphany service at St Martin’s. It seems like a good place to end this talk as well:

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Through the unknown, unremembered gate

When the last of earth left to discover

Is that which was the beginning;

At the source of the longest river

The voice of the hidden waterfall

And the children in the apple-tree

Not known, because not looked for

But heard, half-heard, in the stillness

Between two waves of the sea.

Quick now, here, now, always—

A condition of complete simplicity

(Costing not less than everything)

And all shall be well and

All manner of thing shall be well

When the tongues of flames are in-folded

Into the crowned knot of fire

And the fire and the rose are one.

As you continue or conclude your education, may you journey in faith, led by God’s calling voice toward the unseen intersection of gladness and need, trusting that all manner of thing shall indeed be well.

May you journey in hope, risking disenchantment to discover unexpected joy that costs not less than everything.

May you journey in love, coming to know Christ more deeply and to be Christ to others, until your exploring ends at your beginning and we know fully, having been fully known.

Amen.