Often I have been asked about putting together a grant proposal or a book prospectus. So, I thought I would post here a current proposal (which is very much in progress!) that I plan to send to the Guggenheim Foundation and eventually to a publisher. I hope this might help anyone out there crafting there own proposal/prospectus. And I heartily welcome constructive criticism on the material below.

Book Prospectus: The Riddle of the Religious Other: On the Past, Present, and Purpose of Interfaith Dialogue

Introduction

What is “interreligious dialogue” or “interfaith dialogue” principally for? When did it begin and why? What are its prospects in our post-9/11, “post-secular” world, marked with so many instances where religious forces, paradoxically, have contributed both to violence and peacemaking? These are the touchstone questions behind this book, which possesses both a historical and an ethical dimension. Once completed, it will serve as the first attempt at a synthetic history of interreligious dialogue in the modem age. Organizationally, the book offers a narrative and analysis of four major turning points or “moments” in the history of interfaith dialogue before profiling and evaluating several influential and/or representative contemporary initiatives and institutions that define the contemporary landscape of interreligious dialogue.

Looking Back: Historical Turning Points

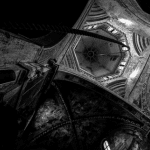

The first turning point whisks the reader back to the sixteenth-century Islamic Mughal Empire in India, during which the Emperor Akbar (1542-1605) inaugurated arguably the first major instance of dialogue among representatives drawn from what Western scholars would later call “world religions.” In his imperial city, Fatehpur Sikri, Akbar built his Ibadat Khana (House of Worship). The evening before Friday prayers, he regularly gathered religious leaders there to discuss and compare views. Islamic scholars were his first interlocutors, but soon Akbar included Hindus, Buddhists, Jains, Sikhs, Parsis, Jews, and Christians. The latter, Jesuits missionaries from the Portuguese mission outpost of Goa, left extensive records of their encounters at Akbar’s court. While little known in the West, these sui generis efforts of interfaith conversation received new attention in the nineteenth century during the heights of European imperialism. Alfred Lord Tennyson immortalized them in his poem “Akbar’s Dream”: “I cull from every faith . . . the best / And bravest counselor and friend.” This poem was published in 1892.

The next year, coincidentally, witnessed Chicago’s World’s Parliament of Religions, which convened in the new American metropolis in conjunction with the Great Columbian Exposition of 1893. This parliament, the second “moment” in this study, helped launch the modern “interfaith movement” and encouraged the development of the academic fields of “comparative religion” and “the history of religion.” Friedrich Max Müller, a founding father of these fields, sized up the significance of Chicago’s 1893 parliament as follows: “Such a gathering of representatives of the principal religions of the world has never before taken place; it is unique, it is unprecedented; nay we may truly add, it could hardly have been conceived before our own time.” While Müller was aware of Akbar’s earlier endeavor, he judged the Chicago affair different in aim and scope—a plausible contention that will be examined in this study.

Inspired by Chicago’s parliament, “the Parliament of Living Religions of the Empire” (1924) in London (UK) constitutes the third focus of this study. At once a show of British imperial grandeur, an exhibition of “Orientalist” understanding, and a genuine effort to build cultural bridges, this little-remembered conference brought scholars, imams, priests, and others to London from 22 September to 3 October of 1924. Among the parliament’s goals, according to its chief architect, the Theosophist William Loftus Harris, were “to show men, in the most impressive way, what and how many important truths the various religions held and teach in common” and “to inquire what light each religion has afforded or may afford to the other religions of the world.” How did this parliament compare/contrast with the prior one at Chicago, I shall ask, and what was the nature of its legacy? (An initial version of this chapter will soon appear as an article in the Journal of the American Academy of Religion under the title “‘A Remarkable Gathering’: The Conference on Living Religions within the British Empire (22 September – 2 October 1024) and its Historical Significance.”)

As instances of interreligious dialogue proliferated in the twentieth century, especially among Protestants, the Catholic Church largely stood on the sidelines. Pope Leo XIII denigrated interreligious dialogue by calling instances of it “promiscuous religious gatherings.” In the encyclical Mortalium animos (1928) Pope Pius XI even condemned dialogue with other branches of Christianity. But this changed abruptly with the Second Vatican Council (1962-65). Accordingly, the fourth focus of this study concentrates on this Council’s ground-breaking “Declaration of the Church to Non-Christians Religions” (Nostra aetate) of 1965, which urged Catholics “to enter with prudence and charity into discussion with members of other religions.” Among other results, the Declaration made possible John Paul II’s convening of religious leaders from throughout the world for a day of solidarity and prayer in Assisi, Italy in 1986—an unprecedented event for the Catholic Church and one that received a diverse range of reactions from within and without the Church. In this chapter, I shall examine the roots of Nostra aetate, discussions of it at the Council, and its legacy and influence.

Looking Forward: Present-Day Examples, Ethical Considerations

These four forays into the past—Akbar’s Court, Chicago 1893, London 1924, and Vatican II’s Nostra aetate (1965)–will prepare the way to examine several examples of contemporary interreligious dialogue and to weigh in on some of the larger, normative issues at stake in promoting interreligious dialogue as a force for peacemaking. I am especially keen to examine the following organizations:

• The World’s Parliament of Religions. Born in 1988 to prepare for the centennial commemoration of the 1893 Parliament in Chicago in 1993, this organization bills itself as “the oldest, largest, and most inclusive” interfaith organization in the world. In recent years, it has staged parliaments in Chicago (1993), Cape Town (1999), Barcelona (2004), Melbourne (2006), Salt Lake City (2015), and (upcoming) Toronto (2018).

• World’s Congress of Faiths. The organization has its roots in the aforementioned Religions of Empire Conference, held in London in 1924. Formally coming into existence at a follow-up conference in 1936, the WCF, according to its mission statement, seeks to “lead the way in building a community of individuals who want to create and enjoy the benefits of interfaith dialogue. . . . In the early days its slogan was ‘faith meeting faith: a rich resource for life’, and this still holds true.”

• Religions for Peace is one of the largest institutions for networking religious actors worldwide. Born in 1970 at a conference in Kyoto, Japan, it is especially eager to turn the fruit of dialogue into purposeful action. According to its website, it seeks to foster “cooperation [that] includes but also goes beyond dialogue and bears fruit in common concrete action. Through Religions for Peace, diverse religious communities discern ‘deeply held and widely shared’ moral concerns, such as transforming violent conflict, promoting just and harmonious societies, advancing human development and protecting the earth. Religions for Peace translates these shared moral concerns into concrete multi-religious action.”

• Interreligious Council of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Međureligijsko vijeće u Bosni i Hercegovini, MRV) was established in 1997. This organization exists to promote dialogue and understanding among Muslim, Orthodox and Catholic groups in Bosnia in the wake of the destructive wars brought on by the collapse of Yugoslavia. (I traveled to Bosnia in March of 2017 and conducted interviews with several individuals, both Christian and Muslim, involved with this council.)

• King Abdullah International Centre for Interreligious and Intercultural Dialogue. Located in Vienna and founded in 2012, this Center seeks “to foster dialogue among people of different faiths and cultures that bridges animosities, reduces fear and instills mutual respect. . . . The Center also combats all forms of discrimination based on culture, religion or belief. . . . Our work is the continuation of a journey to fulfill a vision to bring together religious leaders and governmental representatives in a sustained dialogue for peace.”

• Dialogue Institute. Based at Temple University and founded by Leonard J. Swidler, a veteran of interreligious dialogue, this institute “engages religious, civic, and academic leaders in practicing the skills of respectful dialogue and critical thinking, building and sustaining transformative relationships across lines of religion and culture. It provides resources and creates networks for intra-and interreligious scholarship and action that value difference and foster human dignity.” It sponsors the Journal of Ecumenical Studies, which sees to advance critical awareness of the latest directions in ecumenical and interreligious research.

• Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue. The institutional offspring of Vatican II’s Nostra aetate, this Council has fostered numerous multilateral and bilateral dialogues with religions across the world. According to its mission statement, it exists for three reasons: 1) to promote mutual understanding, respect and collaboration between Catholics and the followers of others religious traditions; 2) to encourage the study of religions, and 3) to promote the formation of persons dedicated to dialogue.

In addition to these organizations, I am also interested in a handful others, which might merit a lingering glance or more during my research. These include the Berkeley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs at Georgetown University; Temple of Understanding; US Institute of Peace; the Interfaith Alliance; European Council of Religious Leaders; International Council of Christian and Jews; among others.

Methodology

T. S. Eliot once wrote “there is no method but to be very ntelligent.” As a baseline, I’ll take this as prescriptive advice! Beyond Eliot’s quip, however, this project will largely rely on qualitative data, drawn from books, articles, archival research, internet sources, and interviews. When appropriate, quantitative data will also be sought out and supplied. The writing will be mostly in the narrative mode, interspersed with analysis and generous quotes from interviews and primary documents. Interviews will focus largely on individuals involved in the aforementioned organizations as well as other active practioners of interreligious dialogue. Sample questions interviewees might receive are as follows:

• What has drawn you to the institution that you currently serve?

• What are some of the challenges and opportunities of presently facing interreligious dialogue?

• What are some concrete instances where dialogue has fostered peace?

• What is the necessary skill-set for those involved in interreligious dialogue and how does one obtain it?

• How can one measure the success of interreligious dialogue?

• What is the relationship between those involved in interreligious dialogue and a country or region’s politics?

• What role has/should educational institutions play in interreligious dialogue?

• What theologies contribute to interreligious dialogue and which ones detract from it?

• Since interreligious dialogue is often undertaken by elites, how can one help the fruits of dialogue “trickle down” to non-elite actors?

• What is the relationship between interfaith dialogue and interfaith social action?

Two additional theoretical touchstones informing the book merit mentioning. These are the notion of critical openness, a term borrowed from the Indian scholar Amartya Sen, and learned ignorance (docta ignoranta), a leitmotif in the writings of the fifteenth-century Catholic Cardinal and scholar Nicholas of Cusa. Together, these notions suggest that the individual engaged in interfaith dialogue, even if exclusively committed to his or her faith, should be open to learning from and questioning of the beliefs of others while at the same time being at once loyal and questioning of their own belief system and its historical embodiments. Put differently, serious and sustained inquiry and intellectual humility are required. In the book, I shall explore how these notions have been fostered or stymied in the past and in the present. I shall ask, in my conclusion, what can encourage and sustain them in the future.

In addition to Sen and Cusa, this project will be enriched by the insights of several other scholarly works. Permit me, briefly, to mention five more:

Diana L. Eck, A New Religious America: How a “Christian Country” Became the World’s Most Religiously Diverse Nation,(HarperCollins 2001), in which Eck demonstrates the massive growth of religious pluralism in the United States (and other Western countries) in recent decades, especially since the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965.

Peter Berger, The Many Altars of Modernity: Toward a Paradigm for Religion in a Pluralist Age, (DeGruyter 2014) in which Berger calls attention to some of the weaknesses of “secularization theory,” long subscribed to by sociologists and other social scientists, and proposes “waxing pluralism” as an alternative to secularization theory as a way of conceputalizing modernity’s impact on religious communities, practices, and beliefs.

Tomoko Masuzawa, The Invention of World Religions. Or, How Western Universalism Was Preserved in the Language of Pluralism (Chicago UP 2005), in which Masuzawa calls attentions to how the notion of “great world religions,” and even the concept of “religion” itself, reflects certain forces and habits of mind within the modem Western academy in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Talal Assad, Discipline and Reasons of Power in Christianity and Islam (JohnHopkins UP 1993), in which Assad, like Mazuzawa, calls attention to the constructed nature of “religion” in Western and global discourse and what this means for interreligious encounters and exchanges. His pluralistic notion of “modernities” (taken from the Israeli sociologist Schmuel Eisenstadt) also offers food for thought for conceptualizing interreligious interactions in the modern era.

Jonathan Sacks, in Not in God’s Name: em>Confronting Religious Violence, (Schocken 2015) in which Sacks argues that engaging religious actors in society in a positive register, not contemning religion as an inherently violent force, is necessary to sustain peaceful interactions among different religious groups.

Finally, principally being a work of history, this project will proceed on the Ciceronian dictum of historia magistrae vita, history as the teacher of life. More fully expressed: we cannot prudently navigate the present and the future without discernment and insight drawn from the past. For interreligious dialogue to thrive in the present and future, it must possess an understanding of its origins and what historical forces have shaped it.