In 1868 the most famous man in America told a group of ministers that their nation had “three great parties: the Republican, the Democratic, and the Methodist Church.” While a nod to the sheer size of the country’s largest Protestant movement, the quip also highlighted how far Methodists had come in what Nathan Hatch has called their “hunger for legitimation, intellectual respect, and cosmopolitan influence.”

That “quest for respectability” was already far along by mid-century, when, Hatch noted by way of example, Methodists accounted for all but two of Indiana’s congressmen. But the “Civil War served as a watershed in Methodist history as well as in national history,” according to historian Doug Strong. “In relation to its influence on American society, Methodism had arrived” (Cambridge Companion to Methodist History, p. 80). After 1865, its adherents held leading positions in everything from higher education and publishing to law and business.

Politics, too. A century that began with Methodism growing on America’s geographical and social frontiers ended with the presidency of William McKinley, who had converted at a Methodist camp meeting, considered entering the ministry, and served as a Sunday school superintendent.

But the first president closely identified with Methodism was not McKinley, but the man elected to his first term the same year as his “three great parties” line: Ulysses S. Grant.

The hero of the Union war effort had been raised in one Methodist household and married into another. Throughout his life Grant continued to attend Methodist churches with his wife Julia, and befriended Methodist leaders like Bishop John P. Newman, who baptized the former president in April 1885, four months before his death from throat cancer.

Nevertheless, there has long been debate about the beliefs of a president who was never formally received into any church’s membership. Grant’s son Jesse reported that his father “was not a pious man and when anyone tells you about having a religious conversation with father, they lie… He was probably what would be called a pure agnostic.” (Jesse also insisted that his father was unconscious during his baptism, and none too happy to learn what had happened.) Ulysses Grant “admired [his mother’s] spirituality,” concludes historian Joan Waugh, “though he declined to share it.”

But another biographer, Edward Longacre, is equally convinced that Grant “was not an atheist as some observers have suggested, nor was he irreligious.” And theological beliefs, however vaguely defined or rarely articulated, may have mattered less to a Methodist than Grant’s consistent commitment to living out his mother’s values and principles: keeping the Sabbath and maintaining “prohibitions against swearing, dancing, gambling, and corporal punishment.”

Likewise, the latest attempt to tell the life story of America’s 18th president describes him as “an observant Methodist [who] was never reluctant to profess his faith.” Fresh off his celebrity as the inspiration for Hamilton, Ron Chernow isn’t interested in Grant’s religion so much as in helping 21st century readers understand why, in his own time, Grant ranked behind only Washington and Lincoln. But for Chernow, Christianity clearly did much to shape a man who was possessed of “a strict Methodist propriety,” an alcoholic whose occasional losses of control “pestered his Methodist conscience,” an increasingly ambitious man who nevertheless refused to “[fall] back on pure egotistical desire, which had never satisfied his Methodist soul.”

Likewise, the latest attempt to tell the life story of America’s 18th president describes him as “an observant Methodist [who] was never reluctant to profess his faith.” Fresh off his celebrity as the inspiration for Hamilton, Ron Chernow isn’t interested in Grant’s religion so much as in helping 21st century readers understand why, in his own time, Grant ranked behind only Washington and Lincoln. But for Chernow, Christianity clearly did much to shape a man who was possessed of “a strict Methodist propriety,” an alcoholic whose occasional losses of control “pestered his Methodist conscience,” an increasingly ambitious man who nevertheless refused to “[fall] back on pure egotistical desire, which had never satisfied his Methodist soul.”

(Religion also may explain why Grant’s life was marked by disastrous failures as well as spectacular successes. In his last years, Grant fell victim to Ferdinand Ward, mastermind of one of the most infamous Ponzi schemes in American history. Chernow argues that Grant’s regular churchgoing helped persuade the con man — and Presbyterian pastor’s kid — that the naive ex-president would be an easy mark.)

A big part of Chernow’s rehabilitation project rests on General Grant’s mid-war conversion to fervent abolitionism and President Grant’s (mostly) strong support for Reconstruction’s experiment in multi-racial democracy. (If you’re wary of committing to a thousand-page biography, at least make sure to read the gripping sections on white violence in the postwar South. Chernow synthesizes historical scholarship on Reconstruction to make clear that Grant was right to see the KKK and similar groups as attempting to undo the defeat of the Confederacy and restore white supremacy.) But Chernow does hint at how religion connected Grant with his most devoted constituency: African Americans. Grant not only met with Methodist pastors and other black clergy during his two terms as president, but spoke at Methodist and other black churches in the South while trying to build support for a third term in 1880.

But apart from such speeches and his inclusion of “Christianization” as a stated goal of his Indian policy, Grant “never exploited religion for partisan gain or pandered to the political agenda of any religious group.” In his famous memoirs, Grant argued both for “the right to worship God ‘according to the dictate of one’s own conscience,’ or according to the creed of any religious denomination whatever” and that “if a sect sets up its laws as binding above the State laws, wherever the two come in conflict this claim must be resisted and suppressed at whatever cost.”

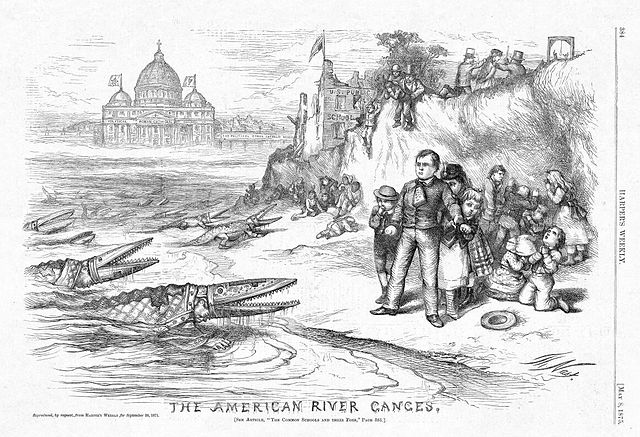

Indeed, his most famous presidential statement referring to religion was a September 1875 argument for the separation of church and state. Having met earlier that day with hundreds of school children in Des Moines, Iowa, Grant then told a veterans’ group that the public school was

the promoter of that intelligence which is to preserve us as a nation. If we are to have another contest in the near future of our national existence, I predict that the dividing line will not be Mason’s and Dixon’s, but between patriotism and intelligence on the one side, and superstition, ambition, and ignorance on the other… Encourage free schools, and resolve that not one dollar of money shall be appropriated to the support of any sectarian school. Resolve that neither the state nor nation, or both combined, shall support institutions of learning other than those sufficient to afford every child growing up in the land the opportunity of a good common school education, unmixed with sectarian, Pagan, or Atheistical tenets. Leave the matter of religion to the family circle, the church & the private school supported entirely by private contribution. Keep the Church and the State forever separate.

Grant endorsed Republican politician James Blaine’s proposed constitutional amendment forbidding the use of public funds for religiously affiliated schools. The Blaine Amendment failed in the Senate, but versions of it were integrated into most state constitutions.

Grant’s speech, like Blaine’s amendment, generated considerable debate at the time, and does to this day. Some have explained it in terms of Protestant nativism, as part of a backlash against growing numbers of Roman Catholic immigrants whose church’s leaders sought public funding for parochial schools. In his history of church-state relations in 19th century America, Steven Green concludes that Grant meant both to deflect attention from the scandals of his second term and

to align the Republican Party more closely with the Protestant cause. Evidence suggests that Republican strategists seized on the Catholic/immigrant issue (as manifested in the school question) as a substitute for the “bloody shirt” when public interest in Reconstruction began to wane. Even the Republican New York Times acknowledged that “an appeal to religious passions was worth twenty-five thousand votes to the Republicans.” Grant likely sought to capitalize on this trend as a way of propelling himself into a third term as president. This fact alone did not make the proposal anti-Catholic—Grant’s remarks criticized sectarianism along with “pagan” and “atheistical doctrines”—although he decried “superstition, ambition and ignorance,” which were code words for Catholicism. But Grant and the Republicans knew that the proposal would appeal to the prejudices as well as the noble instincts of voters.

But Green acknowledges that Catholic response to the speech was mixed. So does Chernow, who later reports that when Grant’s post-presidential world tour took him to the Vatican, the new pope, Leo XIII “regretted that Grant’s Des Moines speech on separating church and state had prevented Roman Catholic instruction in public schools, but he admired the impartial way Grant had applied his policy across all religious denominations.”

Chernow argues instead that Grant primarily meant to encourage public education “as the most effective means to assimilate immigrant masses and heal lingering wartime wounds.” Ten years after the Des Moines speech and mere weeks before his death, Grant struck a similar theme as he neared the end of his memoir. “I feel that we are on the eve of a new era,” wrote the hero of Appomattox, “when there is to be great harmony between the Federal and Confederate.” Reflecting on “the universally kind feeling expressed for me” in his battle with cancer, Grant emphasized that such “feelings” came from different regions, different professions, and “from all denominations—the Protestant, the Catholic, and the Jew….”