The assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy will always remain linked, and not just because they both occurred in the span of two months some fifty years ago this spring.

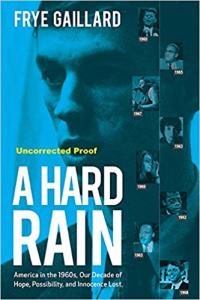

The murders are the fulcrums of Frye Gaillard’s moving new portrait of the 1960s, A Hard Rain. A journalist by training and background, Gaillard has authored a score of books about the history and culture of the American South, most prominently Cradle of Freedom. He is a consummate story-teller, with an eye for the profound emotions at the core of the events that have shaped the contemporary United States. Those emotions remain raw in A Hard Rain. “I hope to offer a sense of how it felt,” Gaillard explains.

Robert Kennedy was no confidante or ally of Martin Luther King. During the 1963 Birmingham campaign, Kennedy was among those who considered SCLC’s protests ill timed. Even if sympathetic toward the cause of civil rights, the attorney general’s was a voice for law and order.

While flying to Indianapolis for a campaign rally in early April 1968, Robert Kennedy learned that King was been shot. When his plane landed, he knew the civil rights leader was dead. Policy warned him not to proceed to his inner-city campaign event, suggesting that it would not be safe for any white person to show his face in the ghetto. The policy refused to provide him with protection. Kennedy went anyway.

Kennedy stood on the back of a flatbed truck and addressed a predominantly African American crowd who did not know King was dead. He told them. Then Kennedy allowed that while he could not walk in their shoes, he knew something of their pain:

For those of you who are black and are tempted to be filled with hatred and distrust at the injustice of such an act, against all white people, I can only say that I feel in my own heart the same kind of feeling. I had a member of my family killed, but he was killed by a white man. But we have to make an effort in the United States … to go beyond these rather difficult times.

Only Robert Kennedy could have delivered that speech. The man who had lost his brother could tell the angry mourners that he understood their grief and rage. There were riots in a hundred American cities that night, but not in Indianapolis.

One of Robert Kennedy’s virtues, especially once he stopped playing Hamlet and decided to run for the presidency, was a willingness to go anywhere and talk with any Americans. He went to rural Nebraska to compete for the small-town white vote, but he didn’t stop walking through the inner cities of Washington or Los Angeles. Kennedy even spent hours with members of SNCC and the Black Panther Party in May.

Kennedy is one of the heroes of A Hard Rain, a man who captured the idealism and promise of the decade as Frye Gaillard experienced it. As a student and young journalist, he found himself in the presence of figures ranging from Bobby Kennedy to George Wallace. For him, Kennedy’s campaign was one of those times “when we seemed on the brink of a different kind of greatness, rooted not only in our national might, but in our capacity for introspection.”

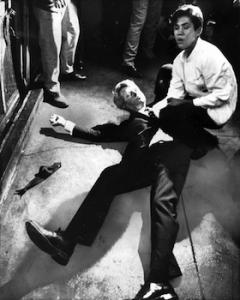

James Earl Ray snuffed out some of that promise in April 1968, and Sirhan Sirhan dealt it another blow when he shot Robert Kennedy the night the New York senator won the California primary. (At a time when primaries played a much smaller role in party nominations, Kennedy may or may not have emerged as the Democratic candidate for the presidency). Whatever his other demons, the Palestinian assassin was angry about Kennedy’s support for the nation of Israel. “No matter how much hope you have,” said Juan Romero, the busboy who held the dying Kennedy’s head, it can be taken away in a second.”

That was Frye Gaillard’s experience as well. He writes about “the hemorrhaging sadness I shared with millions … Even with all of the pain of that last mistake [Vietnam], we could not, in 1968, find a way to break free, nor to make peace with the racial sins of our past. Through all of this, we held to a powerful hope of redemption, nurtured, in part, by our founding ideals, but embodied by the men who had been murdered.”

There are many books that make sense of the sixties. The decade’s many tumults — from the Civil Rights Movement to Vietnam to the counterculture — make for gripping reading even in the hands of narrators far less capable than Frye Gaillard. A Hard Rain is a special book, though. With a particular focus on the South, which outside of the Civil Rights Movement is overlooked in accounts that focus on SDS and the counterculture, Gaillard weaves together religion, conservation, race, and politics into a narrative that pulls readers into and through the decade. Unlike some, he sticks to the actual ten years of the sixties. No “long sixties” here. While decades are arbitrary units for historians, this has its virtues, as he does not feel the need for long chapters narrating the earlier years of the civil rights movement or equally long discussions of Vietnam’s sad denouement. Instead, like the journalist he once was, Gaillard tells the story as it unfolds. It is a story that moves and haunts.