September 29 is the feast of Michael the Archangel, Michaelmas, and the feasts of Gabriel and Raphael are now celebrated on the same day. October 2 marks the celebration of the Guardian Angels.

In 2015, Pope Francis urged his listeners to pay close attention to the instructions they were being given by their holy guardian angels, “God’s ambassadors.” Such words startled some intellectual believers, who had largely consigned angels to the realm of greeting cards, or to New Age eccentricities. In this matter as in much else, Francis was thoroughly in tune with popular belief. Surveys usually show that over three quarters of all Americans believe in angels, including a great many respondents who observe no formal religious practices. The reasons for angels’ popularity today are not hard to fathom: angels appear accessible, comforting, responsive, and non-dogmatic. As the number of unchurched and non-religious Americans grows – as there are more “Nones” – so angels look set to occupy an ever more prominent role in the future spiritual landscape.

As religious figures, though, angels are far more than simple defaults, the residual trace ideas that survive when more complex theologies have receded. The belief in angels is an essential component not just of Christianity but of all the monotheist faiths. The history of angels – and they do indeed have a history – is critical to understanding those faiths. (I am drawing here on my 2017 book Crucible of Faith).

As religious figures, though, angels are far more than simple defaults, the residual trace ideas that survive when more complex theologies have receded. The belief in angels is an essential component not just of Christianity but of all the monotheist faiths. The history of angels – and they do indeed have a history – is critical to understanding those faiths. (I am drawing here on my 2017 book Crucible of Faith).

The creation of angels…. But don’t angels go back to the very start of Biblical religion? Surely, we think, one fallen angel tempted Eve, and God set an angelic warrior to exclude her and Adam from Paradise. How can we speak of a moment of historical origin? Actually, the Bible describes neither of the Eden characters in such angelic terms, nor do they feature much in the Hebrew Bible, the Christian Old Testament. Angels appear sporadically in the Old Testament as divine envoys and as mighty figures in the celestial court, but most references to them are plain and even curt. Angels played no discernible role in the divine plan, they had no individual identity, nor were they given specific functions. They had no assigned responsibility for regions, for natural phenomena, and certainly not for individuals.

What changed? At a particular moment in history, God created angels – or rather, they were called into existence by a radical new view of the nature of God. From the time of the Babylonian Exile in the sixth century BC, the Hebrew people started believing firmly and fiercely that their God was the one absolute deity of the whole universe, besides whom no rival existed or ever could exist. This new insight represented one of the most transformative shifts in human thought, but it posed massive practical problems for religious thought and belief. If God was the Creator and Lord of all, whose worshipers portrayed him in ever more exalted terms, it became ever harder to imagine him interacting directly with mortals, speaking directly with them, or intervening directly in human affairs. So what were believers to make of all the scriptural stories that depicted just such things, that told how patriarchs and prophets had spoken directly with God?

The monotheistic idea logically demanded a whole new class of holy figures, intermediaries who would carry divine commands and warnings, who would inspire prophets and strike sinners. These were messengers – mal’akhim, or, using the Greek translation, angels. It was now not God personally but rather his angels who spoke to the prophets, who bore the news of astonishing events, who fought for the chosen nation against its enemies. The greatest angels were the aristocrats of the divine court, titanic figures utterly removed from the cute angels of today’s popular culture. In a non-monotheistic world, we would not hesitate to call them gods in their own right.

Those figures acquired personal names, which were originally descriptions of divine powers or forces. Gabriel means “the Strength of God,” Michael signifies “Who Is Like God,” Raphael means “God Heals” or “God the Healer,” and Uriel derives from “the Light of God” or “God Is My Light.” But naming angels also personified them, making them appropriate subjects for the invincible human instinct to make sense of the universe by telling stories. Angels starred as vital figures in religious narratives, which featured extensive dialogue, and even individual character development. In turn, the outpouring of literary works in the Inter-Testamental period further focused religious interest on those beings, and prompted still other writings. The later the religious text, the more reliably the angels will be named and given personalities, and even assigned a whole back-story.

So abundant were these works that some ambitious biographer actually could write a detailed life of Gabriel or Michael, as he moved through the centuries, and over multiple civilizations.

The literary emergence of these angels came at a very late stage in the Biblical story – in fact, after the official “closure” of the Hebrew Bible. Around 200 BCE, a series of writings was attributed to the patriarch Enoch, and the resulting apocryphal collection, the first Book of Enoch, is filled with the names and deeds of these hyper-powerful spiritual beings, of Gabriel, Raphael and the rest. They defeated evil forces and rebel angels, casting their enemies into the fiery eternal dungeon (the first literary appearance of Hell); and those good angels will star at the final Judgment. In the 160s BC, Michael and Gabriel both appear in the Book of Daniel, the only canonical Old Testament text that actually names angels. By this point, angels became the rulers for individual nations, even metaphors for the whole society. The angels of one land battled their counterparts in another.

Angels helped resolve another quandary that arose from the idea of a single God. As the familiar question asks, if God is all-powerful and all good, how can evil exist? The question seems insoluble, unless and until we factor in another possible element. Monotheism prevents us from imagining a second god, but what if there is some other mighty spiritual force, call it an angel, who has rebelled against God, and strives against his infinitely good intentions? And what if that one great evil angel commands a hierarchy of lesser beings, and together they constitute a mirror image of the divine order? That idea appears highly developed in the Book of Enoch, where the Lord of Evil is Azazel. He would soon evolve into Satan, and his revolt would be the subject of an enduring heroic literature. A whole theology formed around the consequences of that insurrection, which ultimately became linked to the Garden of Eden story.

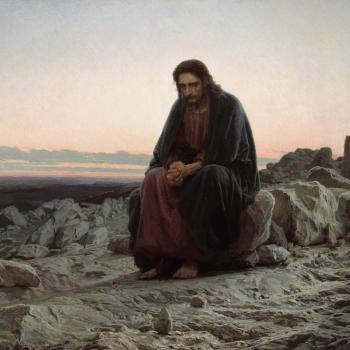

Ideas about angels, both good and evil, reached full maturity in the century or two before the birth of Jesus, and the coming of the Common Era. Angels obsessed the doomsday sect that lived at Qumran in the Judean desert, and which bequeathed the library that we know as the Dead Sea Scrolls. Already in this time, Jewish writers were imagining angels and demons struggling over the souls of individual men and women, offering temptation or urging resistance. On a cosmic scale, Jews portrayed angels of good and evil, Light and Darkness, pitted against each other in the imminent battles that would precede the destruction of the world, and the coming of God’s new order. Similar ideas run through the Christian New Testament, where angels so often play critical roles. Gabriel proclaimed Jesus’s conception to the Virgin Mary. Our New Testaments conclude with the book of Revelation, in which Michael leads the host of heaven in the ultimate cosmic war against Satan and his evil legions.

Angels were associated with apocalypse and Judgment, and in turn Islam inherited that Christian synthesis. Gabriel told Muhammad of his prophetic vocation, and dictated to him the message of coming Judgment found in the Quran.

The growth of the monotheistic religions carried angelic images and stories around the world. In the Christian West, angels had their own church feast days, and they saturated two millennia of Christian painting and sculpture, especially images of Judgment and Apocalypse. Angels were the patrons of highly-sought knightly orders that became the badges of the ruling classes. In time of war, countries adopted angels as their special patriotic symbols, a practice that long outlived the Middle Ages.

Just a century ago, widespread popular belief held that angels had intervened to defend British forces at the 1914 battle of Mons. On the other side, German propaganda turned Michael into something like a national war-god, and the mighty German offensive against the Allies in 1918 was naturally titled Operation Michael. After the war ended, Michael adorned the Victory Medal that the US awarded all its soldiers who had served in what was portrayed as an apocalyptic struggle against worldly evil.

As Christian and Muslim numbers surge across the Global South, angels may yet enjoy a whole new era of popularity as national symbols, and even as battle standards.

In modern times, angels often seem to represent a kind of religious kitsch, a spirituality Lite. Historically, they were anything but that, and they still inspire real devotion among orthodox and seekers alike. Angels deserve and demand their proper history.