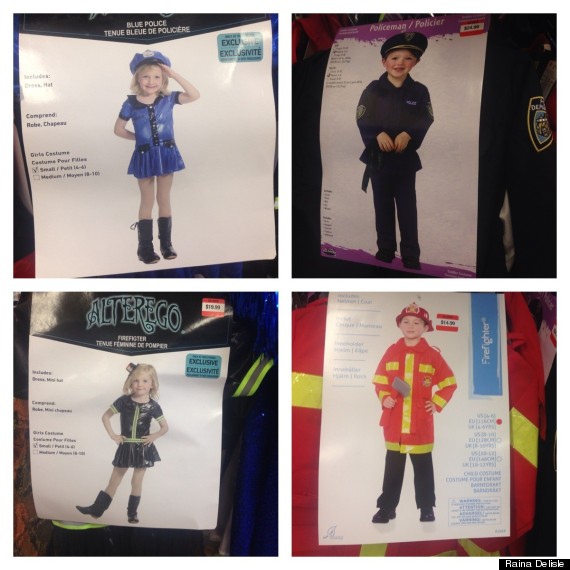

I recently came upon a Huffington Post article titled “Halloween Costumes Are Sexualizing Our Youngest Trick-Or-Treaters.” In the article, blogger Raina Dellisle wrote about going shopping for Halloween costumes with her preschool daughter and coming upon these gendered police and firefighter costumes:

As Dellisle explains:

Halloween costumes that put a sexy spin on uniformed occupations (or anything for that matter) have been popular among women for years, but for little girls? I would be disappointed if my 14-year-old stepdaughter wore this little number, let alone my preschooler. (My stepdaughter is, in fact, dressing up as Rosie the Riveter.)

I absolutely agree that these costumes are sexist—after all, the girl versions of the costumes look nothing like police or firefighter uniforms, as they have been “girlified” beyond recognition—but I’m not so sure that they “sexualize” the girls wearing them as Dellisle’s headline claims. When I look at the pictures above, all I see is a girl in a dress. Sure, the dresses are short, but little girl dresses have often been short.

Let me give you an example. When I was a child, my mother loved sewing clothes for my sisters and I, and sometimes my grandmother, who had sown dresses for my mother, would pass down patterns from the 1960s and 1970s. I did some googling and found pictures of some patterns that remind me of the ones I saw as a girl:

These dresses are extremely short, but I don’t think anyone would accuse the pattern manufacturers of “sexualizing” girls. A short skirt on a little girl does not “sexualize” her by some sort of default. But perhaps the argument is that the police and firefighter costumes above “sexualize” young girls because they’re scaled down versions of sexy Halloween costumes marketed to women. Yet while I can see where this argument is coming from, I don’t think it works.

To illustrate, here’s another quote from Dellisle’s article:

Even the pumpkin costume for preschoolers is sexy: it’s sleeveless and features a black bodice with an orange ribbon that laces up the front like a corset.

Dellisle says the preschool pumpkin costume she saw was sexy because it was sleeveless and had “a black bodice with an orange ribbon that laces up the front like a corset.” She does not include a photo, and I was unable to find one via google. But while searching for one, I did find this costume:

This witch costume is sleeveless and has a bodice with black corset-like laces up the front. Is the baby wearing it being sexualized? The point reaches clear absurdity. What about little girls who want to dress as female hobbits? Are they not allowed to do so because laces up the front would de facto sexualize them?

Here are some more kids’ costumes with corset-like laces up the front:

What is the rule here, exactly? Does a costume sexualize a little girl if it would be sexy when scaled up and worn by a woman? The problem with that argument is twofold.

First, the fact that an outfit would be sexy on a woman does not mean it is sexy on a little girl. In the summer, my daughter often wears short skirts that many grown women would pull off as sexy, but on her they’re not sexy in the least, because she’s a little girl. Do we really want to police little girl’s wardrobes by holding up each piece of clothing and asking “would this look sexy on an adult?”

And that brings me to my second point—what we mean by “sexy” is highly subjective. I often feel sexy in outfits that show almost no skin; indeed, I don’t see sexy as at all synonymous with “shows skin.” I would argue that “sexy” is more about confidence than about the clothing being worn. But when people talk about “sexy” Halloween costumes they seem to be taking about ones that show skin.

And that brings us back to my first point, because a little girl showing skin is not the same thing as a grown woman showing the same skin. When was the last time you looked at a little girl in a bathing suit and thought “sexy”? Never, I hope. Women’s bodies are physically different from little girls’ bodies. Women tend to have curves that little girls don’t. Indeed, women are often seen as sexy when they wear clothing that accentuates their curves, but little girls don’t have those curves.

Now let’s return to Dellisle’s article, because I do have a problem with the police and firefighter costumes in the images she provides. My problem is not that they sexualize girls—I don’t think they do—but rather that they other them. Girls who want to dress as police or firefighters should be given costume options that reflect the uniforms actually worn by police and firefighters (including female police and firefighters). What does it communicate to girls, I wonder, when they’re presented with “girlified” career uniforms that look nothing like what women in those careers actually wear?

Some might argue that little girls already have the option to buy the standard uniform—after all, they could just buy the boy costume—but anyone arguing that does not understand human psychology. Most girls, when presented with two gendered options, will feel pressured to take the girl one. After all, why else would the options be gendered? Choosing the “boy” option means being willing to go against the norms. If the costume shopping is done with friends, it might mean being made fun of; if it’s done with parents, well, some parents would probably refuse to buy a girl a costume that is clearly labeled as a boy costume.

I would like to see one police or firefighter costume design offered. Its packaging would either show only the costume itself or have pictures of two children, one boy and one girl, each wearing the costume. Perhaps for some costumes there would be more than one option for children to choose from, but these options should reflect the various forms of uniform used in a given career rather than being gendered.

I have a serious problem with the gendering of children’s career-based Halloween costumes, but as I see it, the problem is not about “sexualizing” young girls. Rather, the problem is an extension of the othering of girls that we we see throughout products marketed to children. Too often the standard option of a product is marketed to boys, and a “girlified” option is marketed to girls.

This is not what true inclusion looks like.