I don’t remember my first political activity, but my parents do. I’m told I was on the front page of the newspaper, campaigning against Hillarycare. Throughout my entire childhood I was thrust into the political spotlight, expected to campaign for my parents’ political candidates and parrot my parents’ views. At pro-life rallies, I made sure my smallest siblings held signs with slogans like “I’m a child, not a choice” or “Adoption, the loving option.” While still a child, my father left myself and my siblings behind at a rally to meet with a reporter while he got the car. I made sure my 9-year-old sister, the youngest there, had a chance to speak. Thrusting children in front of the microphone—and before the cameras—was just a part of life.

Today, my political views could not be more different from those of my youth. I cut my teeth opposing Hillarycare, and now I’m headed out to vote for her. When I look back at my childhood activism, I’m struck by how uninformed my positions were, and by how often I was used as a prop. This experience makes me profoundly uncomfortable with any pushing of children forward in campaigns, and any touting of children’s endorsements. Children are still figuring this world out, and while they should be allowed to engage in political activism if they want to, they should be understood as in process. There’s a balance between taking children seriously and understanding that children frequently have access to less information than adults, not to mention less freedom to reach out and explore.

Of course, there is a lot of variety within children. Teens have access to more information than first graders, and a child of sixteen will typically a better understanding of the world around them than a child of seven. And I am absolutely not saying that children should not be allowed to campaign, or to support a political candidate. What concerns me is when parents or politicians thrust children, especially young children, into the spotlight. How much agency do these children have, I find myself wondering? How much choice are they given? Are they simply meeting their parents’ expectations, or is this coming from them? And because I frequently cannot tell, I often find myself uncomfortable.

In this post, I want to look at four images tweeted by various presidential campaigns in the last few weeks. These tweets vary—some are obviously objectionable while others aren’t—but they are similar in that they each give us jumping off points for discussion of children’s political agency. When is a child being used as a political prop, and when are they not? What does it look like for a child to exercise political agency, and how can we recognize it?

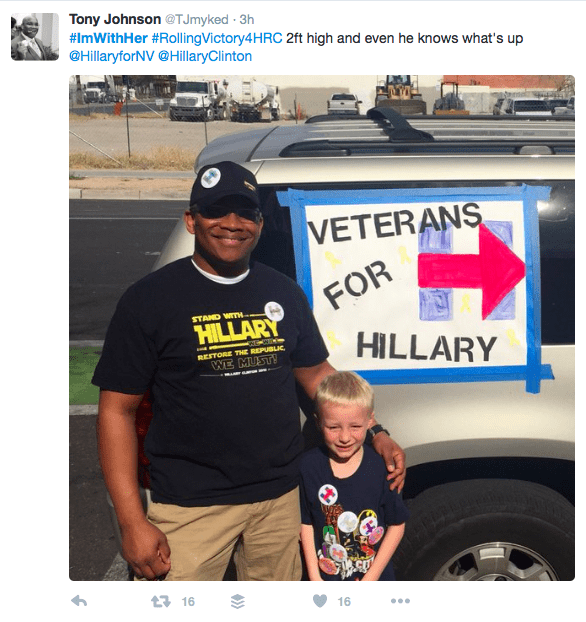

Let’s start with this tweet:

This tweet includes a picture of a man standing by a boy of around five, covered in Hillary buttons. The text reads: “2ft high and even he knows what’s up.”

This kid can’t be more than five. A child of five rarely has access to more political information than that provided by their parents. This child knows his parents support Hillary, but it is extremely unlikely that he has anything near an informed grasp on the issues. I certainly didn’t when I was five. My own daughter is six, and while I’ve tried to explain some of the issues to her, I am well aware that the picture she has of the political sphere is simplistic and one-dimensional—and that’s too be expected. Her understanding of the issues will grow and develop over time—as will this child’s.

I suppose what I’m wondering is this: Why the need to push this child forward in this way? What story is the author of the tweet trying to tell? In what way does it add to the messaging to put a small child forward and say that child “knows what’s up” when that child can’t be more than five? This child may have political opinions—some five-year-olds do—but those opinions are shaped by the information he has access to and are very much fledgling opinions still in development.

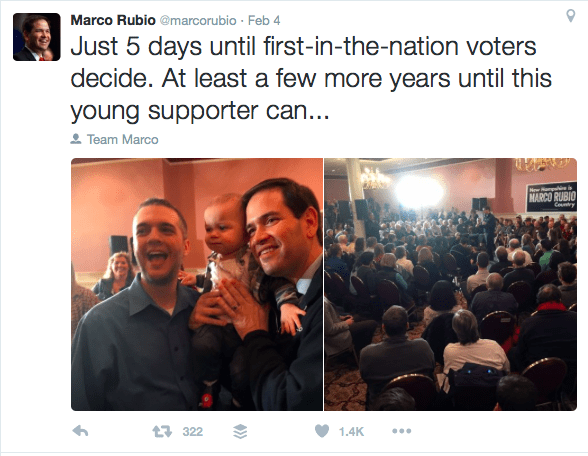

Here’s another one:

The image shows Marco Rubio standing with a man and holding his baby. The text reads “Just 5 days until first-in-the-nation voters decide. At least a few more years until this young supporter can…”

I’m sorry, but this baby cannot be a Rubio “supporter.” This baby does not even know what a president is. And that gets to the root of what bothers me here—you should not assume that a child supports a political candidate just because their parents do. You should assume that a very small child does not have a political opinion one way or another, that a young child may have a very basic grasp of the issues but not more than that, and that an older child or teen will have a more developed understanding depending on how much information they have access to and how much freedom they are given to form their own understandings and explore various ideas.

Let’s change gears a bit with the next two:

This tweet showcases a picture of a father, mother, and daughter, both parents decked out in Bernie gear. The text reads “My family is with #BernieSanders.”

First, this picture is adorable, and second, this girl is absolutely not being used as a political prop in the way the others are. But given the tweet author’s statement that his family supports Sanders (and not simply that he and his wife support Sanders), I’m curious whether and to what extent this girl been allowed to choose for herself which candidate she supports—and how much she wants to be involved. If her parents have given her access to information and the freedom to make up her own mind and she has chosen for herself to support Bernie, and wants to help his campaign, the phrasing used here makes perfect sense. If she hasn’t, her parents are speaking for her politically.

What I’m suggesting is that we should think about to what extent to which we do or do not give children political agency. Growing up in a politically active family, it was simply assumed we children would support whatever candidates our parents did. We were never asked or given an option. I don’t know whether that is the case here—and even if it is, it’s not as big a deal as it is when parents are pushing their children in front of microphones—but I do remember what that was like. You can’t make a decision when you are offered only one option, or are never given a choice to begin with. What I’m trying to get at here is that we need to think consciously about the framework we use for understanding children’s political agency.

One final tweet:

The image shows a woman with two young daughters, a man holding a megaphone in front of the older child, a girl of about eight. The text reads: “Even @HillaryforCO’s youngest supporters came out to say: “it’s time for a woman in the White House!””

As with the girl in the previous tweet, I’m curious how much agency this girl has been given. Has she been coached by her mother in preparation for pushing her in front of a microphone? Does she have access to information? Does she have the option of supporting a different candidate, or of staying out of election altogether? My next-in-age sister hated campaigning, hated being pushed in front of microphones, hated the spotlight, but she wasn’t given a choice. Politics was not optional. Is politics optional for this girl? Does she have the option of staying out of the spotlight without facing pushback from her mother?

As an advocate for children’s rights, I would like to see us protect children’s agency without denying it. I don’t want children trotted out as trained ponies to speak on issues they are not informed on, but I also don’t want to see children denied access to politics altogether, barred from the microphone, or dismissed out of hand. I suppose I want two things. First, I want children to be given access to information and the space they need to make their own decisions. Second, I want adults to understand children’s grasp on politics as provisional and in flux, and to simultaneously take their opinions seriously and give them room to shift over time.

A lot of people expressed consternation when I changed my political opinions in college. They were upset with me and viewed me as a traitor of sorts. How could I have held so tightly to conservative political opinions all through childhood and my teen years only to change my politics so drastically as a young adult? What they didn’t understand was that college was the first time I had access to a full range of information and freedom to form my own opinions. It’s not that I didn’t mean the things I said as as a child, it’s just that my positions were both uninformed and formed in an environment that was not kind to disagreement—an environment that effectively limited my options.

In 2008, a young relative of my husband was a passionate Hillary Clinton supporter even though her parents were politically moderate. She told me then that she thought it was time we had a female president. I was impressed that her parents let her have her own ideas even when her ideas differed from theirs. This girl is a teen today, and is now a supporter of Bernie Sanders—once again in stark contrast to her moderate parents. Once again I am impressed by her parents’ willingness to let her form her own views without undue pushback or shaming. Still, even without parental pressure, she looks back on her elementary school positions as uninformed and perhaps even naive.

If we are going to be serious in our support for children’s interests, we need to give children both the freedom to make up their own minds and the freedom to do so on their own time. We need to give them the space to change their minds as they grow and mature and gain more information and perspective in the future, but we have to do that without dismissing the opinions or ideas they may have in the present—because if there is one thing a child does not need, it’s dismissal. Children should not be denied a microphone if they seek it out, but they also shouldn’t have it thrust in their face by their parents or other political activists. Simply put, children should be allowed to have political agency.