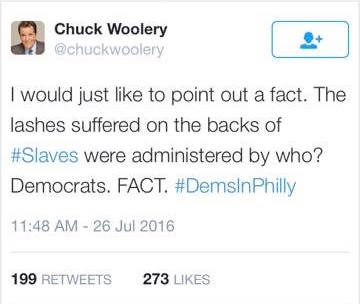

“I wake up every morning in a house that was built by slaves,” First Lady Michelle Obama said in her speech on Monday night. The New York Times confirmed that this is true—the White House was indeed constructed via slave labor. Of course, not everyone was moved by her line. Republican television host and well-known conservative Chuck Woolery tweeted this in response:

Text: I would just like to point out a fact. The lashes suffered on the backs of #Slaves were administered by who? Democrats. FACT. #DemsInPhilly

I really can’t let that go without a response. Because jeez.

Let’s get this out of the way first—Democrats did indeed administer lashes on the backs of slaves during the antebellum period. No one has denied that (that I’ve seen, that is). Whigs also administered lashes on the backs of slaves during the antebellum period. There was no such thing as the Republican Party at that time, just Democrats and Whigs (plus other rotating third party attempts). The Democratic Party was pro-slavery. The Whig Party included more varied voices, resulting in tension that was ultimately the ruin of the party. During the 1850s, the Whig Party splintered over slavery and the Republican Party was formed just before the Civil War out of its debris.

Was the newly formed Republican Party the anti-slavery party? To a point. They became the party of “free labor, free soil, free men.” But what many may not know is that those things were primarily about white men. Those who proclaimed “free labor” and “free soil” were concerned that having to compete with slave labor demeaned white male labor and made white men, well, less than free. In an excellent case study of the wider social conflict—it’s well worth the read—historian Nicole Etcheson has argued that the battle over Kansas during the 1850s had very little to do with the rights of slaves and everything to do with the rights of white people. Southerners argued that whites’ property rights guaranteed them the right to bring their slaves into Kansas. Northerners argued that allowing slavery in Kansas would undermine ordinary whites’ ability to find a job or engage in free labor. Little was said about the rights of slaves.

Then came the Civil War. The Democrats of the South fought to preserve slavery. The Republicans of the North fought to preserve the union. Wait, am I saying the North wasn’t fighting to end slavery? Why yes, yes I am. We’re clear that antebellum abolitionists were so despised in the North that they saw their meeting halls burned, faced mob attack, and sometimes had to flee the country for their own safety, right? Abolitionism was a severely unpopular minority position. Abraham Lincoln freed the slaves partway through the Civil War as a war measure. Lincoln himself wrote that “If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.”

Some Northern soldiers were very impressed by the newly freed slaves they met during the war. These newly freed slaves, often runaways, came by the thousand, frequently taking severe risks in their desire to join the Union forces. In most cases they were assigned grunt labor like digging ditches, but their resolve and their desire for freedom was evident. Unfortunately, the Republican Party ultimately threw these freed blacks under the bus. Why? Because the presidential election of 1876 was contested, and the Democrats offered to give the presidency to the Republican candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes, if Republicans would end Reconstruction, removing all federal troops from the South and by so doing allowing southern whites to restore the old order. And the Republicans took the deal.

Jim Crow didn’t descend on the South immediately after the Civil War. Indeed, it wasn’t fully in place until the 1890s. The removal of federal troops was a key step in the suppression of African American’s rights and the creation of Jim Crow. That year, 1876, was the year black political representation began its steep decline. In 1874 there were eight black men elected to the House and Senate. In 1876 there were four black men elected to those bodies. In 1878 that number dropped to one, and it never fully recovered. After 1898, there were no black men elected to the House or Senate for three decades. Yes, Jim Crow was implemented by southern Democrats. What they did in the South during these years was horrific. But let’s not pretend that the national Republican Party made any real effort to stop it from happening. They didn’t. They turned a blind eye and let it happen.

African Americans stood by the Republican Party during those decades nonetheless. For all of Republicans’ willingness to turn a blind eye to the South’s suppression of African American rights, they were at least not the ones implementing that suppression. There was also a longstanding loyalty to Abraham Lincoln, the Republican president who ultimately freed the slaves, and African Americans often gained more entrance into local Republican politics than the Republicans’ lack of attention to their rights at the national level might suggest. It was within the Republican Party that African Americans fought for recognition and representation during those decades, and in 1920 they succeeded in adding a plank supporting an anti-lynching bill to the party’s platform (it didn’t work out).

But this partnership was not to last.

African American loyalties began changing far earlier than many people realize. Have you heard of the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927? Probably not. But even if you have, you may not be aware of the role the politics surrounding this flood played on the loyalties of African American voters. Herbert Hoover lost the northern black vote when he ran for election in 1932 because of his mishandling of refugee camps during the flood—the African American population of the region was moved on top of the Mississippi River’s levees and then effectively re-enslaved and put to forced labor—and his failure to keep promises he subsequently made to African American voters.

Of course, this shift occurred in part because African American voters suddenly found themselves with a workable second option, embodied in Democratic presidential candidate Franklin Delano Roosevelt. FDR’s New Deal was far from perfect, but First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt reached out to the nation’s African American population and ensured that the New Deal didn’t completely ignore black Americans’ needs. This is why the first African American elected to Congress in the twentieth century was Oscar Stanton DePriest, who ran as a Republican and was elected in 1928, but the second African American elected to Congress in the twentieth century was Arthur Wergs Mitchell, who ran as a Democrat in in 1934. Both men were elected in Chicago, and Mitchell unsurprisingly began his political career as a Republican before becoming a Democrat in the midst of the New Deal.

In 1948, Democratic President Harry Truman signed an executive order ending racial segregation in the military. There is disagreement on where to pinpoint the beginning of the Civil Rights movement, but the 1950s saw Brown v. Board of Education, the Montgomery bus boycott, and the beginning of massive (white) resistance to school integration. The Greensboro sit-ins followed in 1960, and the Freedom Riders in 1961. It was Democratic President John F. Kennedy who stepped in to enforce court-ordered desegregation. While the transition took time, by the late-1960s the national Democratic Party was becoming a (sometimes reluctant) champion of African Americans’ rights while the national Republican Party was going out of its way to reach out to traditionalist whites upset by the Civil Rights movement and the changing status quo.

This is why well-known southern Senator Strom Thurmond switched from Democrat to Republican in 1964. Heck, it’s why the South switched from Democrat to Republican during those years. The South. In 1968, Republican presidential candidate Richard Nixon ran on a platform of “law and order,” running on white disenchantment with a Civil Rights movement that was increasingly perceived as dangerous and militant. In fact, Nixon had an explicit “southern strategy” that involved bringing disenchanted southern whites into the Republican Party—a strategy that ultimately succeeded.

The Democratic Party’s embrace of diversity over the past fifty years does not appear to be simply a cynical attempt to get votes. This year, the Democratic National Convention was opened by Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, the current mayor of Baltimore and an African American woman. Pictures from the convention are awash with racial diversity, and black men and women hold numerous other positions of power within the Democratic Party. Indeed, African Americans make up such a large share of the Democratic electorate that they often have a significant impact on which candidates are selected in party primaries.

We see this realignment reflected in policy, too. Republicans tend to oppose the Black Lives Matter movement and to support voter ID laws that disproportionately affect voters of color, making it more difficult for them to cast a ballot. Democrats, in contrast, tend to support broadening the electorate in ways that ensure that African Americans are not disenfranchised by leftover Jim Crow measures or strategies. Similarly, it is Democrats who are calling for prison reform while Republicans tend to embrace a “tough on crime” perspective that, given the racial bias in our policing and justice system, disproportionately effects African Americans.

So, yes, many (perhaps even most) antebellum slaveowners were Democrats. But we are not living in antebellum America. We are living in the present—a present where powerful Republicans suggest that blacks were better off under slavery, a present where prominent Republican leaders can un-ironically tweet lily white pictures of Capitol Hill interns, a present where the policies of the Democratic Party better reflect the issues of most African American voters than do those of the Republican Party.

We also live in a present where individuals like Chuck Woolrey know far less than they should about the reasons behind our national political parties’ demographic shifts. Let’s not pretend that our two-party system is static or unchanging. We may have a two hundred year history of having only two viable political parties at any one time, but what these parties stand for and who they are comprised in has changed dramatically over the years.