This weekend torch-wielding protesters chanted Nazi slogans as they rallied in defense of a statue of Robert E. Lee which the Charlottesville City Council recently voted to remove. What may be less known is that Corey Stewart, a Republican gubernatorial candidate, has also spoken out in defense of the statue.

“You cannot revise history. Only tyrants attempt to erase history. This is tantamount to denouncing your own heritage,” Stewart said.

…

“I will do whatever I need to, both now and as Governor, to stop this historical vandalism,” Stewart said. “We must fight to protect Virginia’s heritage.”

Historical. Vandalism. Yes, you read that right. Stewart honestly and truly alleges that removing the statute of Lee would be historical vandalism.

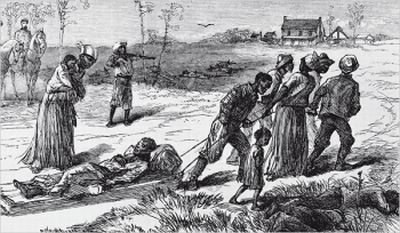

But statues of this sort were never about history; they were always about white supremacy. In the decades after the Civil War, a “Lost Cause” mythology developed in the South that valorized the Confederacy. This historical narrative was accompanied by efforts to end Reconstruction and effectively reinstate slavery, efforts that were largely successful as African Americans were disenfranchised across the South. In other words, the story enshrined by this narrative was not history. It was propaganda.

Have a look at this historical marker in Louisiana:

The text is as follows: “Colfax Riot. On this site occurred the Colfax Riot in which three white men and 150 negroes were slain. This event on April 13, 1873 marked the end of carpetbag misrule in the South.”

What actually happened? Angry at the electoral success of the state’s newly freed black population, an extrajudicial white militia formed in Colfax Parish to retake the courthouse from the white and black Republicans who now controlled it. Understandably concerned, these GOP elected officials called on their mostly black supporters to protect the courthouse from this threat. When the militia trained a cannon on the courthouse, many of its black defenders surrendered. The militia ultimately executed these prisoners and then commenced killing indiscriminately throughout the night. All told, 150 African Americans were massacred.

In case you’re wondering, the white perpetrators of this massacre faced no consequences for their actions. State and local authorities did nothing, and federal attempts to convict several of those involved were ultimately overturned by the United States Supreme Court. This emboldened white terrorist paramilitary groups across the South, and ultimately led to the end of the black franchise in the region. Historians have sometimes referred to the Colfax Massacre as “the day freedom died.”

And yet, consider the historical marker. The marker not only terms the event a “riot” rather than using the more appropriate “massacre,” it also describes the event as “the end of carpetbag misrule in the South.” This, too, is part of the Lost Cause narrative.

Consider the silent film Birth of a Nation, released in 1915. In it, white Southerners are attacked and besieged by blacks—literally hiding in cabins as black mobs shoot from outside—and are ultimately saved by the heroic actions of the Ku Klux Klan.

The clip below shows the South Carolina legislature in session in 1871, after African Americans won a majority of the seats. In the clip, the black legislatures eat fried chicken, drink from open bottles of alcohol, and take their shoes up and put their feet on their desks. The legislature decrees that whites must salute black officers on the street, and legalizes interracial marriage—much to the horror of the men accompanying the elaborately dressed young white women in the gallery.

At the end of the film the next election is portrayed. White onlookers cheer as the Ku Klux Klan forcibly prevents black residents from voting, thus restoring the proper order and protecting white womanhood.

This narrative permeated Southern schoolbooks well into the twentieth century.

The old plantation was a large estate, often consisting of several thousand acres. It was cultivated by hundreds of slaves, whose work was directed by men called overseers. For convenience, the slaves were divided into squads, and over each squad a trusty slave was placed. These “trusties” had endeared themselves to their master by their faithfulness. The “trusties” had to see that their men did the work allotted to them. Each day’s work was planned by the overseer, the night before. At sunrise the signal bell was tapped in the overseer’s yard, where all the negroes were expected to assemble; and there to each squad was signed the work of the day.

These simple-minded people went about their work cheerfully. They were fond of joking and playing pranks, and frequently they tried to outstrip one another in hoeing and picking cotton, humming some tune as they worked. When a squad once got fairly to work, someone would start an old plantation melody; one by one the others would take it up, and soon the air would be filled with the music of their pathetic voices.

At noon the plantation bell was rung, calling the slaves to dinner and to a rest of about two hours; then work was resumed and continued until sundown. Perhaps there never returned from a day’s labor a happier or jollier crowd than the Southern negroes. After supper the banjo and fiddle were brought out, and the negro quarters were alive with music, laughter, song, and dance. At an early hour the noise cased, the lights went out, and the contented slaves were soon asleep.

Many of these materials—whether they were historical markers, works of fiction and movies, or public school textbooks—were not created until decades after the Civil War ended. The book from which the above excerpt hails was published in 1905; the Birth of a Nation was released in 1915; and the Colfax Parish historical marker was not erected until 1950. In many ways, this narrative has not completely disappeared even today.

If you want to know what historical vandalism looks like, well, this is it.

As you may remember, Stewart, the Republican gubernatorial candidate in Virginia, referred to the pending removal of a statute of Robert E. Lee as historical vandalism. How does that statue fit into this discussion? Good question. The statue in question was erected in 1924. It was not erected for simple historical reasons, and its unveiling makes clear the role it played in the community’s “Lost Cause” mythology. Here is an excerpt from the Washington Post, May 22, 1924, page 3:

Statue of Gen. Lee Unveiled as Hosts of His Men Look On

Charlottesville, Va., May 21.—Several thousand veterans of the army of northern Virginia attending the annual Confederate reunion here participated in the exercises marking the unveiling today of the Shrady-Lentelli equestrian statue of Gen. Robert E. Lee, their supreme leader. [description of the parade]

After music by the famed Stonewall band, of Staunton, the Rev. Dr. George L. Petrie, one of the few surviving chaplains of the Confederacy, offered prayer. Then followed the address of the occasion by the Rev. Dr. M. Ashby Jones, of Atlanta, Ga., son of Dr. J. William Jones, known to every living Confederate as the “unrepentant rebel” chaplain. [description of the formal presentation of the statue]

As soon as the demonstration which followed the disclosing of the splendid figure had subsided, President Edwin Anderson Alderman, of the University of Virginia, accepted the monument on behalf of the city.

Tribute to Little Mary Lee

The most dramatic moment of the day was when Judge R. T. W. Duke, master of ceremonies, took 3-year-old Mary Walker Lee from her father’s arms and, standing her on the speaker’s table, said: “I want to introduce you to the great-granddaughter of the greatest man who ever lived.”

A great demonstration ensued. The veterans rose to their feet and cheered, while the little girl waved her hands to the cheering multitude. [description of the reception]

Robert E. Lee was not born in Charlottesville. He never lived in Charlottesville. He had no special attachment to Charlottesville. There was no historical reason for a statute of Robert E. Lee to be erected in Charlottesville. Instead, the statute was erected as part of a Lost Cause mythology—and with full community participation.

As historian David W. Blight wrote in his book, Race and Reunion:

“…by the 1890s, and until at least World War I, the Confederate memorial movement came under the control of new leadership and organizations, especially the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) and the United Confederate Veterans (UCV). The mass of rank-and-file former Confederates … formed the grassroots of Lost Cause ritual activity.

This is what this event was—a ritual. It was presided over by Confederate veterans groups and served as a ritual performed in memory of the “Lost Cause.” It wasn’t about remembering a historical moment. It was about a communal act of worship of a white supremacist racial ideology and historical memory.

Author Jonathan Hennessy describes the event as follows:

On the day Charlottesville’s Robert E. Lee statue was presented to the public in 1924, it was draped in Confederate battle flags and attended by singing, all-white schoolchildren—who themselves were staged and dressed to present as a “living” Confederate flag.

Groups like the Sons of Confederate Veterans and Daughters of the Confederacy had planned and presided over the ceremony. The reigning head of the Sons of Confederate Veterans was a Virginia fish and game official named W. McDonald Lee. During his recent reelection as “Commander-In-Chief” that organization, the convention thronged with attendees confirming they were members of the Ku Klux Klan. Reports in many contemporary newspapers suggest Mr. Lee himself was a Klansman. And Julian S. Carr, the Commander in Chief of the United Confederate Veterans, was an open and avowedly a member of the white supremacist terrorists.

Charlottesville’s Lee statue was not intended to chronicle the history of the Confederacy. It was intended to perpetuate it. In spirit if not in practice. That is the message of the statue—and why it is absurd leave the statue to stand as is, or regard it as a mere innocent signpost of a past era.

Removing this statute is not historical vandalism, as Stewart claims. Rather, the creation of this statue was historical vandalism. The South is littered with statues and monuments and historical markers born of an ahistorical effort to (as Jonathan Hennessy so aptly puts it) perpetuate the Confederacy. These monuments are pieces of history, but not the way Stewart thinks. They are an artifact of white supremacist efforts to perpetuate, uphold, and commemorate a society built on racial violence.

These pieces belong in a museum, where they can be discussed in the context of exhibits focusing on the white supremacist Lost Cause mythology and the creation of the historical memory that undergirded Jim Crow. Moving them there is not an act of historical vandalism; it is, instead, an undoing of historical vandalism.

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!