I became a historian through the Bible and the Reformation.

For starters, at a certain point in my youth, reading the historical books of the Bible (Genesis, Exodus, Joshua through Esther) and the Gospels plus Acts was my way of making church services pass by more quickly. The narratives about the past were usually considerably more lively and interesting (wars, diseases, miracles, prophets, plenty of age-inappropriate material) than what was going on in the present.

Then at some point in high school, I started to see history as a way of understanding the roots of the religion in which I had grown up. I knew that Presbyterians were Protestants, so I set out to learn about the Reformation. I suppose I should have begun with Calvin’s Institutes, but Luther immediately became the leading figure in Christian history for me. Roland Bainton’s biography of Luther (Here I Stand — still in print) became a model for engaging, evocative historical writing.

I loved Luther’s combativeness, his clarity of thought, his battles with the devil, his willingness to employ earthy language, and his marriage. I saw him as a sort of Christian superhero. Perhaps because of stereotypes about Puritans, strict nineteenth-century Methodist morality, and more recent strains of fundamentalism, other Americans tend to regard Protestants as a bunch of [hypocritical] killjoys. Luther, by contrast, thoroughly enjoyed life, and that made it easy for me to enjoy him.

I was reminded of my early love for the Reformation and Luther in particular twin reviews of Steven Ozment’s The Serpent and the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation in the current issue of Books & Culture. Off topic, anyone with a serious interest in religious history as well as contemporary issues surrounding Christianity should subscribe to B&C. The reviews (covering an extremely wide range of Christian and some non-Christian voices) are not accessible online without subscription, so go ahead and pony up the money. It’s a good deal.

The reviews of Ozment on Cranach reminded me of my early interest in Luther. According to Matt Lundin, Ozment argues “that Protestant marriage liberated both sexes from the strictures of medieval asceticism.” Daniel Siedell observes that in what Ozment calls a “second phase” of the Reformation, reformers like Luther recovered “the spiritual integrity of all aspects of domestic family life, from rearing children to marital sexuality.” Cranach, by the way, was the best man at Luther’s wedding, and they served as godparents to each other’s children.

The reviews of Ozment on Cranach reminded me of my early interest in Luther. According to Matt Lundin, Ozment argues “that Protestant marriage liberated both sexes from the strictures of medieval asceticism.” Daniel Siedell observes that in what Ozment calls a “second phase” of the Reformation, reformers like Luther recovered “the spiritual integrity of all aspects of domestic family life, from rearing children to marital sexuality.” Cranach, by the way, was the best man at Luther’s wedding, and they served as godparents to each other’s children.

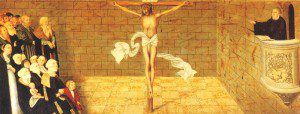

In response to critics who deem Cranach’s art too dogmatic, Ozment notes the “social aspects” (Siedell’s phrase) of his 1547 Wittenberg Altarpiece, in which one sees the presence of Luther and Cranach’s families and friends. Partly because he took business from those on both sides of the ecclesiastical divide, many have doubted Cranach’s professed Protestant faith. As Siedell observes, in the bottom predella (a new word fo r me) of the altarpiece, Cranach is an “old man” receiving “the preached Word” about Christ crucified. I vaguely remember the altarpiece from a mid-1990s trip to Wittenberg.

r me) of the altarpiece, Cranach is an “old man” receiving “the preached Word” about Christ crucified. I vaguely remember the altarpiece from a mid-1990s trip to Wittenberg.

Academia encourages historians toward hyper-specialization. I hate that I do not read as broadly as I did even in graduate school. I’m awaiting my arrival of Ozment’s book on Cranach, eager to get back to an old love. I later gained an appreciation for Calvin, but I still would rather pass my days with Luther.