In recent years, lost or hidden gospels have generated huge public interest, and every few years brings some new discovery: the Gospels of Mary and Judas, even (questionably) the tale of “Jesus’s Wife.”

But the whole narrative of those alternative scriptures is based on a false assumption, or rather a myth. According to the common account, such Other Gospels proliferated in the early church, but were then suppressed, burned or buried, shortly afterwards the Roman Empire adopted Christianity. By 400 or so, presumably, they had altogether vanished from view.

But they hadn’t.

As I have written elsewhere, early alternative gospels continued to be read and venerated right through to the Reformation era and beyond. Indeed, they had something close to canonical status in the mainstream Catholic and Orthodox churches. This was true of such early texts as the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Nicodemus, or the Protevangelium.

More startling, perhaps, is the survival of much more controversial texts that the orthodox churches really did loathe and wanted to suppress. However, when we tell the Christian story in any era on only a European scale – rather, with a West European, Catholic, focus – we miss a very large part of the story. Throughout the Middle Ages, Christian churches flourished across Asia and Africa, and had quite different attitudes to which texts might legitimately be received within the church.

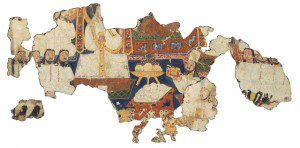

“Lost” gospels also remained available to other bodies who claimed spiritual descent from the apostolic church, but which the Catholic/Orthodox churches regarded as deadly foes. When we bemoan the loss of the ancient Gnostic gospels, we forget how many of these remained in use by the Manichaean faith that was followed by millions across the Middle East and deep into Asia from the fourth century well into the high Middle Ages. In various forms, Manichaeanism lingered on into the seventeenth century in China.

The Manichaeans possessed quite a collection of gospels. In the fifth century, Pope Leo complained that the sect had “[forged] for themselves under the Apostles’ names and under the words of the Savior Himself many volumes of falsehood, whereby to fortify their lying errors and instill deadly poison into the minds of those to be deceived.” Allegedly, they had done this by doctoring canonical gospels in order to remove traces of Christ’s Incarnation or material existence, to deny the reality of the Crucifixion and Resurrection.

But Leo’s statement is misleading, as the sect was in fact using many authentically early gospels in which these orthodox doctrines were absent or underplayed. Among their canonical scriptures were several of the old “Gnostic Gospels,” including a Gospel of Thomas, not to mention Thomas’s Psalms and Acts. (There is some controversy whether the gospel used by the sect was identical with the famous version that emerged from Nag Hammadi). In fact, when early Church fathers referred to the Gospel of Thomas, it was usually in this Manichaean context. In the fifth century, the Decretum Gelasianum condemned “the Gospel in the name of Thomas which the Manichaeans use.”

J. Kevin Coyle writes that, probably, “Manichaeans had access to (in some cases rewriting) a Gospel of Eve, an Euangelium de natiuitate Mariae, gospels of Bartholomew, Peter; and Philip, a Memoria Apostolorum, a Gospel of the Twelve Apostles, and Acts of Philip. In addition, modern commentators have discerned traces of Manichaean reworking of some Nag Hammadi treatises, such as The Origin of the World.” (Manichaeism and its Legacy, Brill 2009, 125). You may recall that the Gospel of Philip earned some notoriety following its modern rediscovery at Nag Hammadi, for a scene implying a sexual relationship between Jesus and Mary Magdalene.

Just what other books Manichaeans might have deployed is open to debate, but the “many volumes” phrase suggests a sizable collection.

We don’t know exactly how long the surviving sect had access to the full panoply of texts described here. It is reasonable to assume, though, that these works really were “lost,” then, closer to the fourteenth century than the fourth. In the intervening centuries, they may have been lost in Europe, but they were not in China or Turkestan.

We appreciate this when we read the great Muslim scholar al-Biruni (973-1048), who was born in what we would now call Uzbekistan, and who traveled extensively in Central Asia and India. As a student of what we would call comparative religion, he had access to a range of texts that moderns can only envy. He certainly knew the canonical Christian gospels, as well as others that today survive only as fragments, if at all.

He also lived at a time when Manichaeanism survived and flourished as a great Asian religion, besides Christianity and Buddhism. In fact, he thought that the Manichaean faith in his day claimed the loyalty of most of the Eastern Turks, besides many believers in China, Tibet and India. Even at this late date, al-Biruni still knew a complete text of the Living Gospel of Mani, written c.260, as well as other Manichaean texts – the Shabuhragan, the Treasure of Life, the Book of Giants, and others. (For a survey of the very rich Manichaean literature circulating in Central Asia at that time, see Hans-Joachim Klimkeit’s wonderful 1992 book, Gnosis on the Silk Road).

But al-Biruni also refers to a treasure trove of Christian texts. “Every one of the sects of Marcion, and of Bardesanes, has a special gospel, which in some parts differs from the gospels we have mentioned.” After describing a Manichaean gospel, he continues, “Of this gospel there is a copy, called The Gospel of the Seventy, which is attributed to one Balamis [or possibly Iklamis]… it is not acknowledged by Christians and others.” (quoted in E. Hennecke and W. Schneemelcher, eds., New Testament Apocrypha, vol. I, 380).

Much scholarly ink has been shed over this passage. Might Iklamis refer to the first century Pope Clement, whose authority was often claimed for heretical writings? How does this reported gospel relate to other works with similar titles cited by early Christian authors, even the Gospel; of the Twelve Apostles? Might this Gospel of the Seventy actually survive in fragmentary form in some of the scattered Christian manuscripts found at or near the oasis of Turfan, the meeting place of the world’s cultures and faiths in these years?

What is not in doubt it that still in the eleventh century, al-Biruni knew a very diverse Christian world in Asia, possibly with schools still following Marcion and Bardesanes, and venerating their scriptures. That is a very long time after we conventionally assume that such diversity would have vanished altogether – at least in European Christendom.

Overwhelmingly, books on Other Gospels focus on those texts written in the first two or three Christian centuries, and on their role in the early church. Usually, authors seek to prove that these works are comparable in historical value to the canonical New Testament, so that such gospels as Thomas, Mary or Judas can tell us at least as much about the historical Jesus as can Mark or John. This is the primary theme of numerous books by such authors as Elaine Pagels, Karen King, Marvin Meyer, Bart Ehrman, and many others.

Almost always, these writers’ interest in those gospels and their impact ends with the establishment of the Orthodox/Catholic church as an official religion in the fourth century. Insofar as recent books discuss later eras, it is with the assumption that those rival gospels and alternative currents of Christianity must surely have vanished.

We see a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. Because these scholars do not pay attention to the post-400 era, therefore not much current literature is available, and that absence leads other writers to assume that the Other Gospels must either have disappeared, or faded into insignificance. If I don’t see it, it doesn’t exist… Effectively then, these books say next to nothing about the role of alternative scriptures between 400 and the new Biblical scholarship of the Enlightenment, some 1300 years later.

If not entirely a blank slate, the issue of alternative scriptures between (say) the fifth and the sixteenth centuries AD has been covered very lightly, and that is a very large portion of the Christian story!