With all the turmoil faced by modern-day Egyptian Christians, I hope it doesn’t seem inappropriate to write more on their ancient beginnings. It should remind us of just how much of the Christian heritage is at stake in these battles.

I have described the oddly obscure nature of the early Egyptian church, suggesting that Christianity must have been very strong in the country, but not necessarily orthodox. Matters changed at the end of the second century, when we suddenly find abundant evidence of a vigorous church in Alexandria, and one that is orthodox enough to be celebrated by historians like Eusebius.

Even so, Alexandrian Christianity remained remarkably flexible, diverse and outward-looking. It really had no option, given the many powerful rivals to orthodoxy – Gnostics of every shade, Jewish-Christians, and of course the very strong traditions of Jewish scholarship.

The first major figure cited by Eusebius (v.11) was the scholar Pantaenus, reputedly the pupil of a Stoic school. Around 180, he became head of Alexandria’s legendary Catechetical School. Colin H. Roberts suggested that he might have taken over a school originally headed by Gnostics like Basilides, and that his primary task was to purge that influence.

Eusebius then tells us a strange and evocative story about Pantaenus:

he was appointed as a herald of the Gospel of Christ to the nations in the East, and was sent as far as India. … It is reported that among persons there who knew of Christ, he found the Gospel according to Matthew, which had anticipated his own arrival. For Bartholomew, one of the apostles, had preached to them, and left with them the writing of Matthew in the Hebrew language, which they had preserved till that time.

This passage has intrigued modern scholars of the New Testament, who debate whether Matthew’s gospel might actually have had a Hebrew original. Most think not, and wonder exactly what Eusebius might be referring to here.

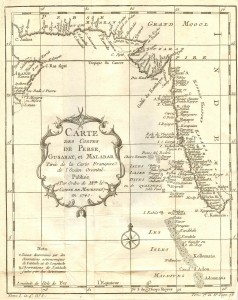

For present purposes, though, it is no less striking that Pantaenus had visited Christian communities in India. That is not implausible. We know of a very early Christian presence there, especially in southwestern regions like Malabar, and Alexandria did have a lively trade with the Indian Ocean world. It’s hard to believe that someone with Pantaenus’s interests would have visited India without at least taking some interest in the local intellectual and spiritual climate.

For present purposes, though, it is no less striking that Pantaenus had visited Christian communities in India. That is not implausible. We know of a very early Christian presence there, especially in southwestern regions like Malabar, and Alexandria did have a lively trade with the Indian Ocean world. It’s hard to believe that someone with Pantaenus’s interests would have visited India without at least taking some interest in the local intellectual and spiritual climate.

One of Pantaenus’s pupils was the brilliant Clement of Alexandria, about whom I can say very little here. Clement was deeply imbued in Hellenistic philosophy, and strove to apply its lessons to Christian theology. Surprisingly for later readers, he was also remarkably open to influences from what would later be designated the heretical fringe.

That is nowhere more true than in his use of Christian scriptures. Clement’s citations reveal a dazzling knowledge of literature and scripture, Christian, Jewish and pagan. Although he did not regard them as fully canonical, he was happy to cite a series of texts, including the Shepherd of Hermas, Didache, Epistle of Barnabas, Apocalypse of Peter, 1 Clement, the Gospel of the Egyptians, Sibylline Oracles, and the Traditions of Matthias. He also had a high regard for the Gospel of Hebrews. Judging by survivals of manuscripts, the Shepherd of Hermas was the most popular Christian text in early Egypt, apart from the Bible itself.

From the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, Clement knew the Apocryphon of Ezekiel, 1 Enoch, and the Assumption of Moses, and assuredly many others. He cites the Exagoge of Ezekiel the Tragedian, a strange attempt to put part of the Old Testament story in the form of a Hellenistic drama.

Clement seemed “practically unconcerned about canonicity. To him, inspiration is what mattered” (quoted here).

His omissions also demand note. He referred very often to the Christian Bible, both Old and New Testament, especially the latter. Even so, and despite his very wide-ranging reading and study, he seems not to have referred to several books of our canonical New Testament, including James, II Peter, and III John. Those gaps are not really surprising, as these books were regarded with great skepticism by contemporary Syriac churches, and would not be included in the Peshitta translation. Nor did Clement cite Philemon, possibly because that is such a brief and ephemeral text.

Both Clement and Pantaenus suggest the remarkable breadth of that early Egyptian church.